Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What exactly is “An Impossibly Normal Life”?

- Why vintage snapshots are a powerful place to rewrite queer history

- How Finley “reimagines” without pretending it’s documentary truth

- What you’ll notice across the “20 vintage photos”

- Where the work has shown up (and why that matters)

- Why this isn’t “just nostalgia”

- Lessons for photographers, writers, and creators (without turning this into homework)

- FAQ: Quick answers people tend to search for

- Conclusion

- Experiences: What it feels like to encounter Finley’s reimagined queer album

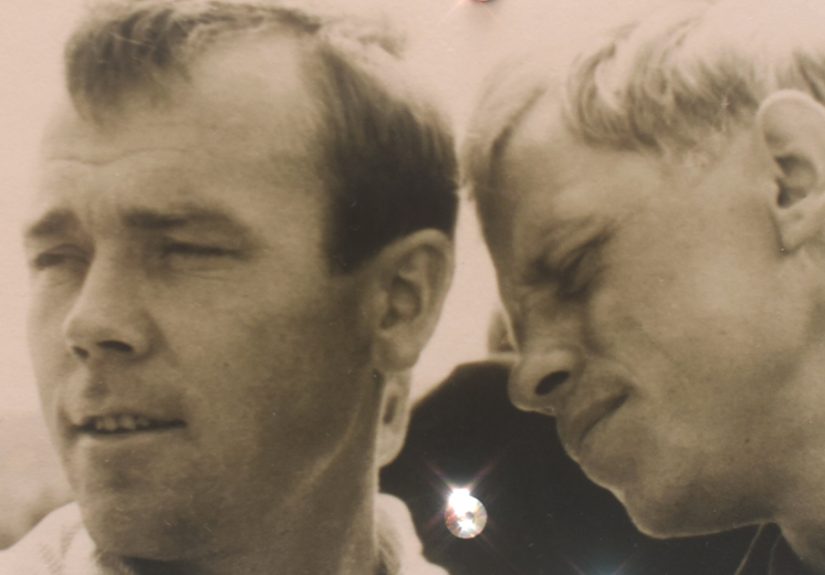

Twenty “vintage photos” sounds like a simple scrolluntil you realize the photos are doing something sneaky: they’re

telling the kind of queer story that history often forced people to whisper. In An Impossibly Normal Life,

Los Angeles–based photographer Matthew Finley reshapes found snapshots into an alternate timeline where queer love

isn’t coded, punished, or quietly edited out of the family album. It’s ordinary. It’s celebrated. It’s the kind of

“normal” that should’ve been boring decades ago.

The result is part photographic project, part invented archive: pages of a life that never happened the way it’s

pictured, but absolutely happened in spirit for countless people who had to negotiate secrecy. And yes, sometimes it

sparklesbecause if the past refused to give you a parade, glitter is a perfectly acceptable retroactive permit.

What exactly is “An Impossibly Normal Life”?

The “20 vintage photos” you’re seeing are excerpts from Finley’s larger body of work, often presented as a cohesive

album-like narrative. The story centers on an imagined uncleoften referred to as “Uncle Ken”whose life is

reconstructed from collected vintage snapshots, ephemera, and subtle visual interventions. The emotional engine is a

familiar one: the ache of realizing someone close to you may have lived a hidden life, and the desire to give themat

least in artthe ease and acceptance they deserved.

Finley has described the spark for the project as a revelation about a possible gay uncle who died not long after

Finley was born. That detail matters because the project doesn’t read like a detached concept piece. It reads like a

family member trying to make sense of silencethen choosing, intentionally, to replace shame with tenderness.

In this reimagined universe, “who you love” isn’t a plot twist. It’s just… Tuesday. The work is explicitly fictional,

but it’s built to feel materially real: like something you could pull from a closet in a shoebox that smells faintly

of old paper and summertime.

Why vintage snapshots are a powerful place to rewrite queer history

Vernacular photography: the “everyday” image with a secret second life

Museums often use the term vernacular photography to describe everyday photographssnapshots, keepsakes,

casual portraitsmade for personal use rather than “high art.” These images are powerful precisely because they were

ordinary. They weren’t trying to prove a point; they were trying to remember a birthday, a beach day, a best friend,

a haircut that felt like a glow-up. And that’s why they’re perfect containers for stories history tried to flatten.

For queer people in earlier decades, “ordinary” photographs could be both refuge and risk. A camera could capture a

real relationship, but the album might need to lie about it. “Just roommates.” “Just buddies.” “Just a pal visiting.”

When you look at vintage photos through that lens, you start to notice how much emotional truth can be crammed into a

supposedly casual frame.

Archives, erasure, and the long wait to be seen

Major institutions now collect and share LGBTQ-related materialsfrom portraits and Pride images to documents and

demonstrationsbecause the historical record was never neutral. It was selective. For a long time, the safest queer

archive was the one that didn’t announce itself.

Finley’s project belongs to a wider cultural shift: making room for queer presence in the places it was excluded,

including the “family-friendly” spaces people used to argue queer life didn’t belong. A family album is as

family-friendly as it gets. That’s the point.

How Finley “reimagines” without pretending it’s documentary truth

Found photos, new narrative gravity

The backbone of the project is found imagery: vintage snapshots sourced and collected, then reorganized into a story

with emotional continuity. Rather than treating each image as an isolated artifact, the project treats them like

sentences in a memoir. Sequencing does a lot of work: childhood moments, teenage rites, friendships, uniforms, trips,

parties, domestic scenes, romance, and commitment.

That structure is important: it insists queer life is not only tragedy, not only crisis, not only “coming out.”

Instead, it’s the full range of human lifeawkward school phases included. (If straight people get to have

questionable prom outfits preserved forever, queer people deserve equal archival embarrassment. It’s only fair.)

Craft as a visual language: glitter, flowers, and the right to be extra

One of the most distinctive features in reviews of the work is Finley’s use of tactile embellishmenthand-applied

glitter, rhinestones, and decorative flourishes. These additions do two things at once. First, they broadcast joy:

they make the images feel cherished, like someone loved them enough to decorate them. Second, they expose the act of

editing history. The glitter says: “This is constructed.” And then it adds, gently: “So are a lot of the stories you

were taught to accept.”

In other words, the project isn’t trying to trick you. It’s inviting you to imagine a better baselinethen notice how

unreasonable it is that this baseline ever felt “impossible.”

What you’ll notice across the “20 vintage photos”

Even when you only see a selection, the series tends to repeat a few emotional motifs. Here are the themes that make

the images feel like a cohesive life rather than a random flea-market collage:

-

Everyday domestic happiness. Kitchens, living rooms, backyards, and casual get-togethersspaces

where acceptance becomes routine rather than exceptional. -

Friendship as survival. Photos with “the gang,” school friends, or chosen-family energy that feels

like a support system before the term was popular. -

Public milestones that queer people were often denied. Proms, weddings, anniversaries, and

celebratory rituals that many couples had to postpone or hide. -

Uniforms and institutions. Images that evoke military or formal settings can be especially loaded:

they highlight the tension between belonging and concealmentthen rewrite it toward dignity. -

Flirtation and tenderness without punishment. Small gesturesstanding close, touching hands,

laughing togethertreated as normal, not dangerous. -

Nature as a soft reset. The outdoors appears repeatedly in Finley’s broader practice: nature as a

place to exhale, to be unobserved, to exist without performing for anyone else.

Put simply: the photos don’t shout. They don’t need to. They achieve something rareran atmosphere where queer life

isn’t a debate topic. It’s a life.

Where the work has shown up (and why that matters)

This project hasn’t lived in just one corner of the internet. It’s been presented through photography organizations

and exhibitions, reinforcing that the work is meant to be experienced as a series, not just consumed as a one-off

“cool before-and-after” moment.

-

Museum and gallery contexts. Exhibitions have framed the project as a meditation on queer identity,

historical erasure, and reclaimed joyinviting viewers to read it slowly, like an album. -

Photography-center programming. Photography institutions have positioned the work as both personal

and political: a creative response to marginalization and a blueprint for acceptance. -

Online features that broaden access. The “20 photos” format works well online, but it also acts as

an entry point into a longer narrative for readers who may never set foot in a gallery.

That range matters because it mirrors the project’s own argument: queer stories belong everywhereon walls, in books,

in archives, and yes, in the casual spaces where people share photos for fun.

Why this isn’t “just nostalgia”

Nostalgia is often sold as comfort: the warm glow of simpler times. Finley’s work uses the glow, but refuses the lie.

For many queer people, “simpler times” were simpler only if you were allowed to be yourself without consequences.

That’s why the project hits: it takes the visual language of mid-century comfort and swaps the underlying social rule.

The reimagining is not an attempt to erase struggle or rewrite real history as painless. Instead, it asks a different

question: What could have been possible if acceptance had been normal? That question has teeth. Because once

you can picture it, it becomes harder to justify why anyone should have to fight for it now.

Lessons for photographers, writers, and creators (without turning this into homework)

1) Sequencing is storytelling

Finley’s project reminds creators that a “series” isn’t just a folder of images with the same vibe. The order of

moments creates meaning. Childhood before romance. Friendship before belonging. Ordinary days around big milestones.

That structure gives the viewer something to inhabit.

2) Material choices can carry the message

The glitter and embellishment aren’t decoration for decoration’s sake. They function like visual stage directions:

“This moment is sacred.” “This person mattered.” “This joy is intentional.” If you’re a creator, that’s a useful

reminder: medium choices can be part of the argument, not just the packaging.

3) “Reimagining” works best when it’s honest about being imagined

The project’s power comes from clarity: it’s an artifact from another world. That transparency creates trust. It

allows viewers to feel the emotional truth without confusing the work for literal documentation.

FAQ: Quick answers people tend to search for

Is “An Impossibly Normal Life” a real family album?

It’s presented like an album, but it’s an invented narrative built from collected vintage snapshots and crafted

interventionsan alternate history designed to visualize acceptance.

Why use found photographs at all?

Found photos carry the texture of real lifeclothing, posture, settings, and the casual intimacy of snapshots. They

let the work speak in the visual grammar of everyday memory.

What’s the main takeaway of the “20 vintage photos” selection?

That queer joy isn’t newand it doesn’t need to be treated as a special category. The images argue for a world where

love is routine, not controversial.

Conclusion

“20 Vintage Photos Show A Reimagined Queer Life By Matthew Finley” isn’t just a headline-friendly galleryit’s a

compact version of a bigger, braver idea. Finley takes the most familiar visual object we havethe family snapshot

and uses it to build a timeline where acceptance is the default setting. The work doesn’t deny history’s harm. It

refuses history’s limits.

And if you leave the series with a lump in your throat or a weird urge to call someone you love, that’s not you being

dramatic. That’s the project doing its job: reminding you that “normal” should never have been an impossible dream.

Experiences: What it feels like to encounter Finley’s reimagined queer album

People often talk about “representation” like it’s a box to checkadd one character here, sprinkle a rainbow there,

done. But the experience of seeing queer life treated as unremarkably ordinary can land in a totally

different place in your body. It’s less like being handed a trophy and more like realizing you’ve been holding your

breath in a room you didn’t know was stuffy.

Imagine scrolling through the photos late at night, the way you’d wander through a friend’s social feed. At first,

your brain registers the familiar cues: aged paper tones, old-school poses, a sense of “this happened a long time

ago.” Then you notice something softer: the closeness doesn’t feel like it’s performing for the camera. It feels like

the camera just happened to catch it. That’s when the quiet shock arrivesbecause so many queer stories from “back

then” are framed as tragedies or cautionary tales. Here, the photos refuse the usual script. Nobody is being punished

by the narrative. Nobody is reduced to a problem that needs solving.

For LGBTQ+ viewers, especially, the experience can be oddly practical. You’re not only seeing romance or prideyou’re

seeing logistics. You’re seeing the small life-stuff that makes a relationship real: birthdays, friends who stick

around, awkward outfits, trips that weren’t perfect, moments that are funny in hindsight. That’s a rare gift. It says,

“Your life is allowed to be boring sometimes.” And that might be the most radical compliment a piece of art can give.

For viewers who aren’t queer, the experience often flips expectations. Instead of asking, “How is this different from

me?” the images quietly ask, “How is this not the same?” A couple being affectionate at a celebration. Friends

packed into a frame like they’re building a little universe. A family scene that says, “You belong here.” Those are

universal emotional beats. The only “difference” is the history that made those beats feel risky for some people and

effortless for others. Seeing the effortless versionseeing it without apologycan help someone understand the harm of

the old rules without needing a lecture.

There’s also a tactile, craft-like warmth to the whole thing. When you notice decorative flourishessparkle,

embellishment, little visual signals of careit can feel like someone is actively blessing the past. Not pretending it

happened exactly this way, but insisting that the people who could have lived this way deserved it. That

sensation is strangely tender: it’s art behaving like a relative who finally knows what to say, even if it’s late.

And then there’s the aftereffect. Many people don’t finish a series like this and immediately become historians.

Instead, they become memory-editors in the best sense: they start re-reading their own photo boxes with new questions.

Who isn’t labeled? Who got called a “friend” forever? Which silences were protection, and which were simply habit?

Finley’s work doesn’t answer those questions for you. It just makes it feel possibleand maybe necessaryto ask them.

Ultimately, the experience is a reminder that acceptance is not an abstract policy argument. It changes the texture of

a whole life. It changes what gets photographed, what gets kept, what gets captioned, and what gets celebrated. If a

handful of reimagined vintage snapshots can make that visible, then the real-world version of that acceptance is not

only imaginableit’s overdue.