Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Meet the USS Johnston: A “Tin Can” With a Big Attitude

- The Battle off Samar: A Last Stand in the Pacific

- Lost to the Deep: Decades of Mystery

- First Clues: RV Petrel Spots Debris

- Deepest Wreck Dive in History: Caladan Oceanic Confirms the Johnston

- Why the USS Johnston Wreck Matters

- What the Wreck Tells Us About the Final Moments

- Looking Ahead: Other Wrecks, Ongoing Stories

- Experiences and Reflections: What It’s Like to “Visit” the USS Johnston Wreck

- Conclusion: A Heroic Destroyer, Finally Seen Again

Imagine diving four miles straight down into the Pacific, into water so dark and

pressurized it could turn a car into scrap metal in a heartbeat. Somewhere in that

cold black lies one of World War II’s boldest “tin can” destroyers: the USS

Johnston. For decades, the ship’s exact resting place was a mystery,

its story carried mostly in survivor memories and history books about the

Battle off Samar. Now, thanks to modern explorers, high-tech

submersibles, and a lot of stubborn curiosity, we’ve finally come face to face with

this historic wreck.

In this article, we’ll look at how explorers located the USS Johnston wreck, why the

ship’s last battle has become legendary, and what the discovery means for naval

history, deep-sea technology, and the families of the crew. Grab your virtual

dive helmetwe’re going down deep.

Meet the USS Johnston: A “Tin Can” With a Big Attitude

The USS Johnston (DD-557) was a Fletcher-class destroyer, one of the

workhorse ship types of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Laid down in 1942 and

commissioned in October 1943, she measured about 376 feet long and carried five

5-inch guns, torpedo tubes, depth charges, and anti-aircraft weaponsplenty of bite

for a relatively small ship.

Destroyers like Johnston were nicknamed “tin cans” because of their thin hulls. They

were fast and aggressive but not exactly built to trade punches with battleships.

Think of them as the boxing lightweight who somehow keeps getting matched with

heavyweightsand still steps into the ring anyway.

Johnston’s commanding officer, Commander Ernest E. Evans, was known

for being fearless and blunt. At the ship’s commissioning, he reportedly told his

crew that he intended to take them into harm’s wayand that anyone who didn’t like

that idea could leave now. Not many COs open with “this is going to be dangerous,”

but Evans meant it.

The Battle off Samar: A Last Stand in the Pacific

Taffy 3 vs. the Japanese Center Force

On October 25, 1944, Johnston was part of Task Unit 77.4.3,

nicknamed Taffy 3, a group of six small escort carriers guarded by

three destroyers and four destroyer escorts. Their job? Provide air support and

anti-submarine coverage for the invasion of Leyte Gulf in the Philippinesnot duke

it out with the main Japanese fleet.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened. A powerful Japanese forcefour

battleships (including the giant Yamato), cruisers, and destroyersslipped

through the San Bernardino Strait and surprised Taffy 3 off the island of Samar.

The Americans suddenly found themselves facing ships that massively out-gunned and

out-armored them.

Johnston Charges Into History

While the escort carriers turned away and started laying smoke, Commander Evans

didn’t wait for detailed orders. He turned Johnston toward the Japanese

fleet and launched a solo torpedo run, firing her guns at the heavy cruiser

Kumano and setting her ablaze. At least one torpedo blew off

Kumano’s bow, forcing her out of the battle.

That attack drew the attention of multiple Japanese ships. Johnston took hits from

shells as large as 6-inch and 8-inch, losing power in some systems and suffering

heavy damage. Still, once she disengaged briefly under a smoke screen and rain

squall, Evans turned her back into the fight again to support other American

destroyers and protect the escort carriers.

Over the next hours, Johnston punched far above her weight, firing at battleships

and cruisers, laying smoke for the carriers, and drawing fire away from the more

vulnerable vessels. Eventually, the destroyer was hit repeatedly, lost power, and

was left dead in the water. Around 09:45, Evans gave the order to abandon ship. The

USS Johnston sank with about 186 of her crewand with her

reputation as one of the most tenacious destroyers in the Pacific.

Evans was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, and Johnston

received the Presidential Unit Citation and six battle stars for her World War II

service.

Lost to the Deep: Decades of Mystery

After the battle, survivors knew roughly where Johnston had gone down, but that

didn’t mean she was easy to find. The sinking took place near the

Philippine Trench, in some of the deepest waters on Earth. Depths

in this area exceed 20,000 feet (over 6,000 meters), far beyond what traditional

research submarines could safely visit for many years.

For decades, the ship existed mostly in memoirs, naval archives, and books like

The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors. The exact location of the wreck was

unknown. Unlike shallower wrecks that divers and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs)

can visit regularly, Johnston remained in the category of “someday, when we have

the tech.”

First Clues: RV Petrel Spots Debris

The first real break came in 2019, when researchers aboard the

late Paul Allen’s research vessel RV Petrel used a deep-diving ROV

to explore the seafloor off Samar. They found a debris field containing a 5-inch

gun, propeller shaft, and other wreckage consistent with a Fletcher-class

destroyer. At depths around 20,400 feet, it was the deepest wreck located up to

that time.

The catch: the ROV couldn’t safely reach the deepest parts of the site, and the

debris alone wasn’t enough to positively identify the ship as Johnston rather than

another lost destroyer such as USS Hoel. Researchers had a strong hunchbut not yet

a confirmed ID.

Deepest Wreck Dive in History: Caladan Oceanic Confirms the Johnston

Enter the DSV Limiting Factor

In 2021, undersea explorer and former U.S. Navy officer Victor Vescovo

and his company Caladan Oceanic mounted a new expedition to the

Samar battlefield. Using the titanium-hulled submersible

DSV Limiting Factor, designed to withstand full ocean-depth

pressure, Vescovo and his team were able to dive repeatedly to more than 21,000

feet (about 6,456 meters).

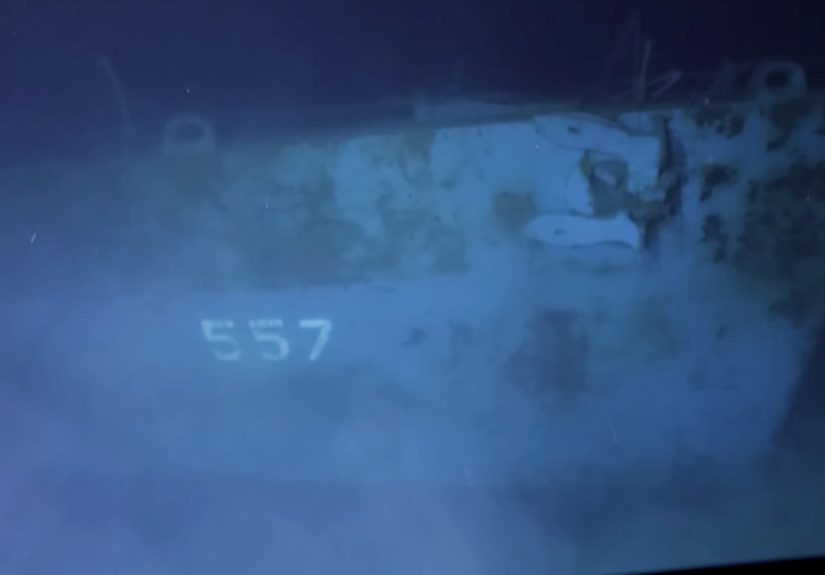

On two eight-hour dives, the team surveyed the wreck lying upright on the seafloor.

They documented key featuressuch as the bow shape, gun mounts, superstructure,

and, most importantly, the clearly visible hull number “557” painted on the side.

That left no doubt: this was USS Johnston.

The World’s Deepest Known Shipwreck (For a While)

At the time of the survey, Johnston was recognized as

the deepest shipwreck ever visited and identified, sitting more

than 20,000 feet below the surfaceabout 62 percent deeper than where the Titanic

rests in the North Atlantic. Later, Vescovo’s team found USS

Samuel B. Roberts (“Sammy B”) even deeper, but Johnston still holds a special place

as the first “tin can” from Samar to be found and fully surveyed.

High-definition video shows the forward two-thirds of the destroyer resting

upright. Her main guns are still trained off to starboard, just as they were during

her final minutes as she fired on the Japanese fleet. Many of the shell holes

visible in the hull line up closely with survivor accounts and wartime action

reports.

Why the USS Johnston Wreck Matters

A Powerful Memorial to “Tin Can Sailors”

For historians and families of the crew, the wreck is more than rusty steel. It’s a

war grave and a physical memorial. U.S. policy treats such wrecks

as protected sites, not salvage opportunities, so the team took care not to disturb

the ship.

The visual confirmation of Johnston’s condition helps validate survivor stories

about where and how the ship was hit. It also personalizes the Battle off Samar.

Reading that a destroyer fought battleships is one thing; seeing the torn metal,

the still-aimed guns, and the hull number glowing faintly in deep-sea light is

another. It drives home the cost of that courage.

Pushing the Limits of Deep-Sea Exploration

The expedition also marks a major step forward in

deep-ocean exploration technology. Diving a crewed submersible to

more than 6,400 meters, maneuvering it around a wreck, and capturing sharp imagery

is no small feat. Techniques developed for exploring sites like the Johnston wreck

can be applied to studying deep-sea ecosystems, mapping the seafloor, and even

monitoring critical underwater infrastructure.

In other words, chasing a World War II shipwreck isn’t just nostalgiait’s a test

bed for the next generation of undersea science and engineering.

Connecting Past and Present

Finally, the rediscovery of USS Johnston helps connect modern audiences to a

rapidly receding generation. Fewer and fewer World War II veterans are alive to

tell their stories. High-quality video of the wreck, carefully contextualized by

historians, gives us a powerful way to keep those stories alive for students,

museum visitors, and casual history nerds alike.

What the Wreck Tells Us About the Final Moments

Detailed analysis of the wreck has allowed naval historians to reconstruct parts of

Johnston’s last battle with surprising precision. A 3-D model created from

expedition data shows that the forward two-thirds of the ship is relatively intact,

while the aft section appears to have broken off and remains undiscovered or

scattered.

Shell damage on the superstructure and hull matches accounts of hits from Japanese

cruisers, destroyers, and secondary batteries from battleships like Yamato. Some

large holes may correspond to massive shells that over-penetrated before

detonatingor didn’t explode at allhelping to explain how the ship stayed

afloat as long as it did despite overwhelming fire.

The guns frozen in place at high elevation, still pointed toward where the Japanese

fleet once was, are a visual echo of Johnston’s reputation: fighting to the end,

even when the odds made survival nearly impossible.

Looking Ahead: Other Wrecks, Ongoing Stories

USS Johnston is only one of several ships from the Battle off Samar and the wider

Battle of Leyte Gulf that lie in deep water. Other wrecks, such as

USS Samuel B. Roberts and USS Hoel, have also been located or are the subjects of

ongoing search efforts. Each new discovery adds another puzzle piece to the picture

of what happened on that chaotic October morning in 1944.

As technology improves, we can expect more detailed mapping, more 3-D modeling, and

more respectful documentation of these underwater battlefields. The key is balance:

use modern tools to learn as much as possible while remembering that these are also

graves and deserve the same respect as any military cemetery on land.

Experiences and Reflections: What It’s Like to “Visit” the USS Johnston Wreck

Most of us will never sit inside a deep-sea submersible looking out at a shipwreck

four miles down. Still, thanks to expedition footage, interviews, and reports, we

can piece together what that experience is likeand why it leaves such a deep

impression on the people who make the journey.

Descending Into the Dark

Explorers describe the descent to the USS Johnston wreck as a surreal, almost

meditative process. The submersible leaves the surface in bright daylight, then

slowly passes through bands of fading blue until the outside world is completely

black. The only light is whatever the crew brings with them. It takes hours to

fall through that water column, with the passengers feeling more like they’re in

space than under the sea.

During these hours, the team monitors depth, systems, and navigation, but there’s

also time to think. For many, this means reflecting on the sailors who went down in

this same stretch of ocean under very different circumstancesclinging to rafts,

struggling with injuries, and hoping rescue ships would find them in time.

A Sudden Encounter With the Past

When the submersible finally nears the seabed, the pilot begins sweeping with

sonar and lights, searching for any hint of structure on the bottom. In the case of

the Johnston, the first glimpses are often hauntingly ordinary: a patch of sand,

then a line that turns into part of the hull, or the faint glow of “557” emerging

in the headlamps.

Explorers often talk about a jolt of emotion at that moment. Even for seasoned

deep-sea crews who have visited other wrecks, seeing a famous “tin can” destroyer

appear out of the darknessand knowing what happened to the people aboardcan be

overwhelming. There’s excitement at finally confirming the wreck, but also a sense

of solemn responsibility to get everything right.

Working Carefully in a Place That Isn’t Yours

Operating a submersible around a wreck at these depths is a delicate balancing act.

The team wants detailed imagery and mapping, but they also know the wreck is

legally and morally a protected site. That means no touching, no

collecting souvenirs, and no disturbing the structure more than necessary

for navigation.

Pilots report that maneuvering around twisted metal and collapsed structures feels

a bit like flying a helicopter inside a cathedral made of steel. One wrong move

could damage the wreckor the submersible. So movements are slow and deliberate.

Lights trace along gun barrels still aimed skyward, across torn plating, and over

torpedo racks now half-buried in sediment.

Emotional Impact on Explorers and Families

Many expedition members have military backgrounds themselves, which adds another

layer of connection. They aren’t just visiting a famous ship; they’re visiting the

final resting place of sailors who wore the same uniform. Some have described

quietly reading out the ship’s name and hull number over the submersible’s

intercom, or pausing operations briefly to “stand in silence” in their own way,

four miles underwater.

For families of the crew, seeing images of the wreck can be bittersweet. On one

hand, the footage confirms what history has always said: Johnston fought hard and

died hard. On the other, it offers a sense of closure. The ship isn’t lost in some

abstract senseit’s there, in a real place, still bearing scars that match

the stories passed down through generations.

Why These Deep-Sea Visits Matter

Ultimately, deep-sea expeditions to wrecks like USS Johnston are about more than

technology or record-setting depth numbers. They’re about knitting together the

human experience across time. From the sailors who fought on deck in 1944, to the

explorers piloting submersibles in the 2020s, to the people watching documentary

clips at home, everyone shares a piece of the same story.

When we “visit” the Johnstonphysically with a sub or virtually through video and

articleswe’re reminded that history isn’t just dates and diagrams. It’s real

people, real risks, and real courage, all still resting quietly on the bottom of

the sea.

Conclusion: A Heroic Destroyer, Finally Seen Again

The discovery and survey of the USS Johnston wreck bring together

everything that makes this story compelling: daring naval combat, cutting-edge

technology, deep-sea exploration, and a powerful human legacy. From Commander

Ernest Evans’s fateful decision to charge a vastly superior enemy, to modern

explorers diving to record-breaking depths, the Johnston’s story spans generations.

Today, the ship rests quietly on the seafloor, guns still aimed toward where the

enemy once was. Thanks to the work of explorers, historians, and engineers, we can

now see and study that final poseand, more importantly, remember the people who

put the ship there. For the “tin can sailors” of Taffy 3, the rediscovery of the

USS Johnston is a long-overdue salute from the deep.