Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Who Were Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck?

- How the “Lonely Hearts” Scheme Worked (Without the Gory Details)

- A Mini Timeline: Why 1947–1951 Still Gets Quoted

- Where Do They “Rank” in True-Crime Cultureand Why?

- Ranking Factor #1: The case feels like an early blueprint for modern romance scams

- Ranking Factor #2: It’s a partnership story, not a solo-offender story

- Ranking Factor #3: The victim count is debated, which invites myth-making

- Ranking Factor #4: Media coverage became part of the story

- Ranking Factor #5: The nickname is unforgettable (and that’s part of the problem)

- Opinions: What People Disagree About

- How the Legal System Framed the Case

- Pop Culture: Why Movies Keep Coming Back to This Story

- Myth-Busting: Separating the Core Facts from the Fog

- What This Case Teaches Today: Dating Safety and Scam Awareness

- How to Write About Fernandez and Beck Without Doing Harm (A Quick Checklist)

- Experiences: How People Engage With the Fernandez–Beck Story Today (500+ Words)

- Conclusion: What Their “Ranking” Really Reveals

Content note: This article discusses a historical criminal case in a non-graphic, context-first way. The goal here isn’t to sensationalize violenceit’s to understand why this case still shows up in “rankings,” what people disagree about, and what we can learn from how the story has been told.

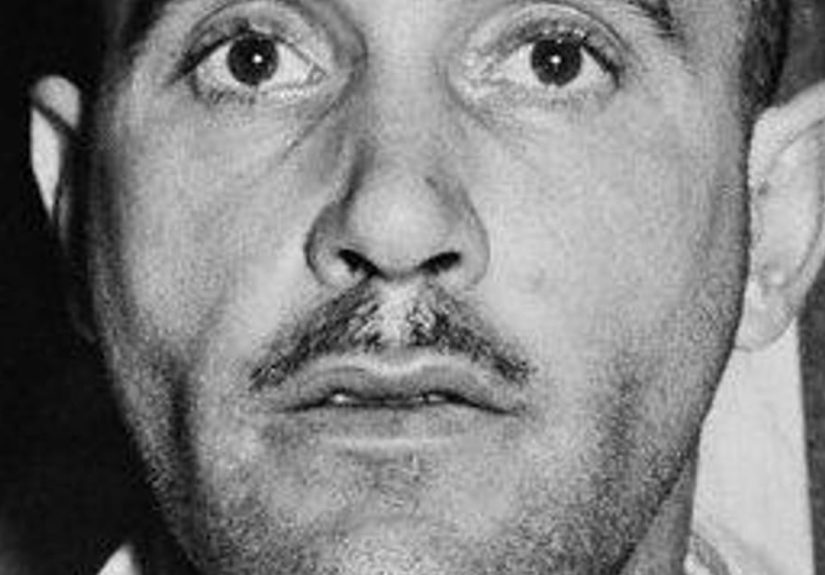

If true crime had a “most likely to become a cautionary headline” category, Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck would be permanently nominated. Known by the tabloid nickname the “Lonely Hearts Killers”, they operated in the late 1940slong before dating apps, verification badges, or the modern concept of “red flags” (though they did manage to wave plenty of those anyway). Their story continues to resurface in documentaries, films, podcasts, and listicles, often framed as one of America’s most infamous criminal couples.

But “rankings and opinions” are tricky territory. Turning real tragedy into a leaderboard can flatten the human impact into trivia. So instead of scoring them like a sports team (please don’t), we’ll look at what drives their notoriety, how different sources characterize the case, where the facts are solid versus disputed, and why the public’s fascination keeps rebootinglike a sequel nobody asked for, yet somehow it still gets greenlit.

Who Were Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck?

In broad terms, Fernandez was a con man who targeted women seeking companionship through personal ads and correspondence. Beck became his partner in the scheme. Together, they used deceptionoften presenting themselves in a way that lowered suspicionto gain trust, access money, and control living situations. The criminal activity escalated into homicide, leading to their arrest in 1949 and execution in 1951 at Sing Sing Prison in New York.

This basic arc appears consistently across mainstream historical summaries and later reporting: the couple used “lonely hearts” ads to identify vulnerable targets, moved through multiple states, and left behind a trail of theft and death that investigators struggled to quantify with certainty. Some accounts cite a small number of confirmed victims; others discuss a much higher suspected total. That uncertainty is one reason the case remains so debatedand so frequently re-packaged.

How the “Lonely Hearts” Scheme Worked (Without the Gory Details)

At its core, the scheme followed a grimly familiar logicfamiliar, at least, to anyone who’s ever seen a romance-scam warning from a bank or consumer protection agency. Replace “DMs” with “letters,” and the structure is painfully recognizable:

1) Identify people looking for connection

Personal ads and lonely-hearts clubs offered a pool of people explicitly searching for companionshipoften older adults, widows, or individuals living alone.

2) Build trust fast

They used charm, flattery, and the language of commitmentfuture plans, marriage talk, urgency. When someone is hopeful, urgency can feel like romance. That’s the trap.

3) Create “proof” that lowered suspicion

Accounts commonly describe them presenting themselves as relatives or as a respectable pair. The presence of a second person can make a situation feel “safer,” even when it isn’t.

4) Move from emotional access to practical access

Money, valuables, bank accounts, and property weren’t side queststhey were the point.

5) Control the environment

Getting victims isolated or under the couple’s roof made the scam easier to run and harder to detect.

That’s the mechanism that keeps the case relevant: it’s an early, extreme example of romance fraud plus predatory coerciona pattern that still exists today, even if the technology changed.

A Mini Timeline: Why 1947–1951 Still Gets Quoted

Different sources slice the timeline differently, but a consensus outline looks like this:

- Late 1940s: Fernandez targets women via personal ads and correspondence; Beck becomes involved as a partner.

- 1947–1949: The couple travels and continues the fraud; homicide occurs within this spree period.

- 1949: Arrest and investigation intensify; the case becomes a national sensation.

- 1949–1950: Trial proceedings and appeals.

- March 8, 1951: Execution at Sing Sing Prison in New York.

Those dates matter because they anchor the story in a specific post–World War II social climate: rapid movement between states, booming print media, and lonely-hearts matchmaking as a mainstream, mail-based social tool. It was a world where your “profile” was a paragraph in print and your “verification” was… vibes. (Not ideal.)

Where Do They “Rank” in True-Crime Cultureand Why?

In popular true-crime ecosystems, Fernandez and Beck frequently appear in lists like “infamous couples,” “crime duos,” or “killer partners.” Their “ranking” is less about a single authoritative list and more about a repeated pattern: major outlets and entertainment media keep placing them among the most notorious American criminal couples.

So what drives that recurring placement? These are the most cited “ranking factors,” for better or worse:

Ranking Factor #1: The case feels like an early blueprint for modern romance scams

Even without modern tech, the narrative structure resembles what we now call “romance scam playbooks”: targeted outreach, fast intimacy, financial extraction, isolation. That familiarity makes the case “sticky” in readers’ mindsbecause it doesn’t feel like a relic. It feels like a warning label.

Ranking Factor #2: It’s a partnership story, not a solo-offender story

Public fascination spikes when crime is framed as a relationshipespecially when the relationship appears volatile, co-dependent, or transactional. People argue over who led, who followed, and how responsibility should be understood. The “couple” element adds narrative tension in a way that single-offender cases often don’t.

Ranking Factor #3: The victim count is debated, which invites myth-making

Some sources describe a small number of confirmed victims; others cite suspicions of up to around twenty. That range fuels speculation, and speculation fuels content. (It also fuels misinformation, which is why careful phrasing matters.)

Ranking Factor #4: Media coverage became part of the story

From the start, the case wasn’t only investigatedit was consumed. Later cultural portrayals kept the story alive and sometimes reshaped it, emphasizing certain themes: jealousy, deception, and the “strange romance” angle. That framing can eclipse victims unless writers actively resist it.

Ranking Factor #5: The nickname is unforgettable (and that’s part of the problem)

“Lonely Hearts Killers” is a catchy label. Catchy labels travel farther than complicated truths. That’s why the case persists in pop cultureand why responsible coverage has to work harder to keep the story grounded.

Opinions: What People Disagree About

When you read across historical summaries, legal overviews, and cultural criticism, the opinions tend to cluster around a few recurring debates. Here are the big oneswithout pretending there’s a clean, comfortable answer.

Opinion Debate #1: “How many victims were therereally?”

This is the most common dispute. Some accounts emphasize a limited number of proven killings (based on what was tried in court and what evidence could support). Others highlight broader suspicions and the couple’s alleged claims. The safest, most accurate way to write it is: they were convicted in New York in connection with one murder, and investigators suspected additional victims beyond what could be fully proven in court.

Opinion Debate #2: “Was this primarily a money scheme that escalatedor violence from the beginning?”

Many retellings frame the arc as “fraud first, then escalation.” That framing can help explain how scams slide into coercionbut it can also accidentally sound like minimizing. A better approach is to state plainly: the scam was predatory from the start, and the outcomes became lethal.

Opinion Debate #3: “Who was driving the partnership?”

People argue about leadership: was Fernandez the planner and Beck the enforcer, or was Beck the catalyst that pushed the scheme into murder, or were they mutually reinforcing? Different portrayals push different answers. The reality is that partnership crime often involves dynamic power shiftscontrol, dependence, fear, manipulationrather than a single permanent “boss.”

Opinion Debate #4: “Does media portrayal educateor exploit?”

Film and TV adaptations have a habit of polishing rough truths into dramatic arcs: detectives with personal demons, lovers with “fatal attraction,” a sense of inevitability. Critics often point out that this can make the story more watchable while making the victims less visible.

How the Legal System Framed the Case

Legal summaries of the case emphasize procedure and outcomes: jurisdiction, extradition, the death penalty, appeals, and the mechanics of trial. One reason the case is frequently discussed in law-oriented references is that it reflects how prosecution choices can narrow a sprawling series of suspected crimes into a single, winnable caseespecially when evidence varies by state and by incident.

In plain English: even when investigators suspect more crimes, the courtroom is built on what can be proven to a jury under specific rules. That differencebetween investigative suspicion and legal proofhelps explain why the case’s “numbers” remain debated.

Pop Culture: Why Movies Keep Coming Back to This Story

The Fernandez–Beck case has been reinterpreted multiple times, including notable films that treat it with very different tonessome gritty and intimate, others structured as a procedural with detectives and pursuit. Film criticism around these adaptations often highlights a recurring tension: audiences want the “mystery” and “thrill,” while the subject matter demands restraint and moral clarity.

Two titles commonly referenced in discussions of this case are:

- The Honeymoon Killers (1970) frequently cited as an influential, stark portrayal that stays close to the killers’ relationship dynamics.

- Lonely Hearts (2006) a later adaptation that places more emphasis on law enforcement pursuit and period storytelling.

Readers’ opinions about these portrayals often split along lines like “realistic vs. exploitative,” “victim-centered vs. killer-centered,” and “historically grounded vs. melodramatic.” That split isn’t just tasteit’s ethics. The same story can be told as a warning or as entertainment, and sometimes it’s uncomfortably both.

Myth-Busting: Separating the Core Facts from the Fog

Because this case has been told so many times, it attracts “sticky myths”details repeated because they’re dramatic, not because they’re the most reliable. If you’re writing about Fernandez and Beck (or reading someone who is), these are the clarity rules that keep the story honest:

Rule #1: Use careful language about victim totals

Say “suspected” or “believed” when discussing higher numbers, and separate that from what was proven in court. Avoid treating the maximum estimate like a settled fact.

Rule #2: Avoid turning psychological claims into certainties

Popular retellings sometimes lean on occult/voodoo beliefs, mental instability, or “jealous rage” as a neat explanation. Those elements can appear in accounts, but they don’t “explain away” choices. People are responsible for what they do, regardless of the story’s dramatic accessories.

Rule #3: Don’t let the couple’s “romance” swallow the victims

The more a retelling focuses on the couple’s relationship drama, the easier it is to forget the human beings harmed by the crimes. A responsible piece keeps the victims’ reality in frame, even if names and personal histories are limited in public summaries.

What This Case Teaches Today: Dating Safety and Scam Awareness

You don’t need to live in the 1940sor reply to a lonely-hearts adto learn from the underlying pattern. Many modern safety tips exist precisely because romance fraud and coercive manipulation are still around. Here are practical, non-alarmist takeaways that apply today:

Trust is earned, not speed-run

Fast intimacy can feel flattering. It can also be a tactic. If someone pushes commitment quickly, treat it as a cue to slow down, not a cue to keep up.

Verify identity with more than stories

Consistency matters: details that match across time, friends, work, and basic documentation. If someone’s life story changes depending on the dayor they resist simple verificationthat’s information.

Keep boundaries around money and access

Requests for loans, bank details, property access, or “temporary help” can be the hinge where romance becomes exploitation. It’s okay to say no. It’s also okay to ask someone you trust for a reality check.

Meet safely and keep your people in the loop

Public places, your own transportation, and a friend who knows where you are: boring safety habits are underrated heroes.

These tips aren’t about paranoia. They’re about keeping power balanced when emotions run highbecause scammers count on people feeling too embarrassed to pause and ask questions.

How to Write About Fernandez and Beck Without Doing Harm (A Quick Checklist)

If your goal is a responsible, high-performing web articleone that ranks without being grossthis checklist helps:

- Don’t glamorize: avoid romantic framing, “iconic couple” language, or admiration-coded adjectives.

- Keep it non-graphic: summarize facts without dwelling on violent details.

- Separate confirmed facts from estimates: be explicit about what’s proven versus suspected.

- Center prevention and context: explain how scams work and what institutions learned.

- Use culture coverage carefully: mention films/books as interpretation, not evidence.

Done right, “rankings and opinions” becomes a study of why society fixates on certain casesand how we can engage without turning suffering into entertainment confetti.

Experiences: How People Engage With the Fernandez–Beck Story Today (500+ Words)

Because the Fernandez–Beck case sits at the crossroads of romance, deception, and historical media frenzy, people tend to “experience” it in a few predictable modern ways. One common entry point is the “top crime duos” or “infamous couples” list formatreaders stumble across the nickname, pause at how old the story is, and then realize the structure feels surprisingly modern. Many people describe that moment as unsettling: the technology changed, but the manipulation pattern didn’t.

Another experience is film-first discovery. Some viewers watch a dramatizationoften without knowing it’s based on real eventsand then go looking for the historical record to separate what was invented for drama from what’s grounded in reporting. That fact-checking journey can be eye-opening. Viewers often notice how adaptations can shift emphasis: sometimes the pursuit by detectives becomes the emotional center, sometimes the couple’s toxic dynamic becomes the hook, and sometimes (unfortunately) the victims fade into the background. That realization frequently changes how people watch true crime afterward. They start asking: “Who is this story for?” and “What is it teaching me?”

For students and researchers, the case is often encountered as a discussion starter about gender expectations, postwar loneliness, and tabloid influence. The 1940s setting matters: personal ads and correspondence were socially acceptable ways to seek connection, especially for people who felt isolated. In classroom discussions, the case can become a lens on vulnerabilityhow social isolation and financial insecurity can make someone more exposed to manipulation. The “experience” here is less about shock and more about social analysis: how communities, institutions, and media environments shape risk.

True-crime podcast listeners often describe a different kind of engagement: they compare multiple retellings. One version might emphasize the scam mechanics, another might lean into relationship drama, and another might focus on the investigation. As listeners notice these differences, they develop sharper media literacy. They recognize that even “fact-based” storytelling involves choiceswhat to include, what to omit, what to dramatize, and what to soften. That is a surprisingly empowering experience: the story stops being a single fixed narrative and becomes a study in how narratives are made.

There’s also a practical, present-day experience that shows up in comment sections and discussion forums: people connect this case to modern online dating and romance scams. They talk about friends who were catfished, relatives who were financially exploited, or moments when someone tried to rush intimacy and isolate them. In that sense, the Fernandez–Beck story becomes a historical “case file” that helps people name uncomfortable dynamicsespecially the way shame can keep victims silent. Readers often say the most valuable part isn’t the history itself, but the reminder that asking for help early is smart, not embarrassing.

Finally, for many readers, the experience is emotional but quiet: it’s a recognition that behind every sensational nickname are ordinary people whose lives were interrupted. That recognition can change how someone reads true crime. Instead of chasing the most shocking detail, they start looking for context, accountability, and prevention. And honestly? That’s the kind of “ranking” we could use more of: not “most infamous,” but “most useful lessons learned.”

Conclusion: What Their “Ranking” Really Reveals

Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck remain “high-ranking” in true-crime notoriety not because the story is stylish or cinematic, but because it sits on a haunting overlap: romance and risk, trust and exploitation, media appetite and moral responsibility. The factslate 1940s crimes, 1949 arrest, 1951 executionare the spine. The opinionsvictim totals, partnership dynamics, and ethical storytellingare the debate that keeps the case circulating.

If you’re reading or writing about them today, the most valuable approach is also the simplest: keep it factual, keep it non-graphic, and keep the focus on what prevents harm. Because the goal shouldn’t be to remember the nickname. The goal should be to recognize the patternso fewer people get trapped by it.