Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Best Time” Really Means (Hint: Not a Date on a Calendar)

- The Lost Decade Paradox: Sometimes the “Worst Start” Becomes the Best Setup

- “Time in the Market” Beats “Timing the Market” (Because Math Has No Feelings)

- Lump Sum vs. Dollar-Cost Averaging: The Best Strategy Is the One You’ll Stick With

- What If the Market Is at All-Time Highs?

- A Simple “Best Time to Invest” Playbook You Can Actually Follow

- So… What’s the Best Time to Invest?

- Real-World Experiences: Lessons That Stick (About )

- Conclusion

The “best time to invest” question is the personal-finance version of “what’s the best diet?”

Everyone wants a single magical answer, preferably delivered in a fortune cookie, preferably with

a side of guaranteed returns.

But investing doesn’t run on magic. It runs on math, behavior, and timeplus a tiny dash of humility

because the market has a long history of laughing at our predictions. The good news? You don’t need

a crystal ball. You need a plan you’ll actually follow when your group chat is screaming “SELL EVERYTHING”

and your app is flashing red like a microwave that’s been running too long.

What “Best Time” Really Means (Hint: Not a Date on a Calendar)

Most people think “best time to invest” means finding the perfect entry pointbuying right before

a big rally and never experiencing a drawdown that makes you question your life choices.

In real life, “best time” usually means:

- When you have money available (after essentials and an emergency buffer).

- When your time horizon is long enough that short-term chaos doesn’t matter much.

- When your portfolio matches your stomach (risk tolerance is real, and it doesn’t care about your spreadsheets).

- When you can automate it so you don’t rely on willpower at 11:47 p.m. on a Tuesday.

Translation: the “best time” is less about the market’s mood and more about your ability to stay invested.

The market rewards patience. It punishes improvisation.

The Lost Decade Paradox: Sometimes the “Worst Start” Becomes the Best Setup

If you’ve ever hesitated to invest because you feared “what if I start at the top?”congratulations, you are

a normal human. This fear gets extra spicy when people talk about “lost decades,” those stretches where stocks

go nowhere for years and headlines make it sound like capitalism has been canceled.

Why a lost decade can be terrible

A long flat or choppy market can be psychologically brutal. If it convinces you that investing is a scam and

you quit, then yesstarting in a rough period can be genuinely damaging. Your returns don’t suffer first;

your behavior does.

Why a lost decade can be wonderful (if you’re still saving)

Here’s the weird part: if you’re a net savermeaning you’re adding money regularly for yearslower prices are

not your enemy. They’re a discount. A “lost decade” can become a decade of buying more shares with the same

monthly contribution, setting the stage for stronger results when markets recover.

One historical-style thought experiment often discussed in long-term investing circles goes like this:

invest a fixed amount every month for 10 years, then stop contributing and let the portfolio ride for 10 more.

In a roaring bull market, the early results look amazing. In a rough decade, the early results look disappointing.

But when you extend the timeline, the decade where you accumulated shares at lower prices can end up with the

stronger finish.

The punchline: you want bear markets early and bull markets later. Your younger self wants cheaper

shares. Your older self wants higher prices. Starting during ugly times can be an advantageif you keep showing up.

“Time in the Market” Beats “Timing the Market” (Because Math Has No Feelings)

Market timing is seductive because it feels like control. In practice, it often becomes “panic-selling with

better branding.”

The market’s best days often hide inside its worst moods

Many of the strongest single-day gains happen during volatile periodsoften near bear markets and recessions.

That’s why jumping in and out is so risky: you don’t just have to be right about when to leave; you also have

to be right about when to come back. Miss a handful of those rebound days, and long-term results can shrink

dramatically.

This is one reason long-term investing advice keeps sounding boring: “stay invested” isn’t catchy, but it’s

hard to beat. As one example of how costly it can be, research-driven illustrations show that missing just a few

top-performing days over long periods can meaningfully reduce ending wealth.

The “return gap” problem: investors often earn less than the funds they buy

Another sneaky reason timing hurts is that many investors don’t experience the full return of the investments

they own. They buy after a run-up, sell after a drop, then repeat the cycle like it’s a gym membership they

keep paying for but never use.

Studies that compare fund returns to “investor returns” (which incorporate real cash flows in and out) often find

that investors capture less than the fund’s published performance because of poorly timed buying and selling.

In plain English: the fund did fine; humans did human things.

Lump Sum vs. Dollar-Cost Averaging: The Best Strategy Is the One You’ll Stick With

If you’re investing money as you earn it (like a 401(k) contribution), you’re effectively dollar-cost averaging

already. The harder question is what to do with a chunk of casha bonus, inheritance, business sale, or a pile

of “I’ve been waiting for the dip” money.

What the math tends to favor

Historically, markets have tended to rise over time, which gives lump-sum investing a natural advantage:

you’re invested sooner, so you have more time exposed to market growth. Research from major providers has

often concluded that immediately investing a lump sum has a higher probability of outperforming spreading it

out, simply because cash on the sidelines doesn’t compound in the same way.

What real life tends to favor

The trouble is that people are not spreadsheets. If investing a lump sum will keep you up at nightor if it

makes you more likely to bail at the first scary headlinethen the “optimal” strategy becomes suboptimal fast.

Dollar-cost averaging can reduce regret risk: if the market drops after your first purchase, you haven’t put

everything in at once.

A practical compromise many long-term investors use:

- Invest a portion right away (so you’re not frozen in cash).

- Schedule the rest over a short, defined period (like 3–12 months).

- Keep the schedule automatic, so you don’t renegotiate with yourself every week.

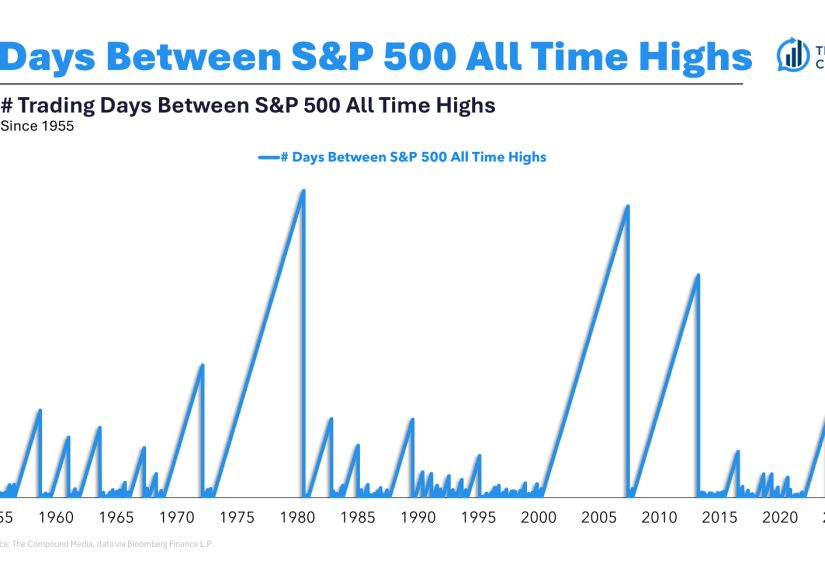

What If the Market Is at All-Time Highs?

This is where people whisper, “Should I wait?”as if the market can hear them (it can, and it will immediately

do something rude).

All-time highs feel dangerous because they sound like “the top.” But markets often make new highs over long

stretches because that’s what growing economies and compounding earnings tend to do. Waiting for a “better”

price can turn into a permanent lifestyle, like saying you’ll start exercising once you find the perfect sneakers.

The better question isn’t “Are we at a high?” It’s:

- Do I have a time horizon that gives my investment room to breathe?

- Is my mix of stocks and bonds appropriate, or am I accidentally running a thrill ride?

- Am I investing consistently, or am I trying to outsmart randomness?

A Simple “Best Time to Invest” Playbook You Can Actually Follow

1) Build your shock absorbers first

Before you invest aggressively, have an emergency fund (even a modest one) and address high-interest debt.

The goal is to avoid becoming a forced seller when life happensbecause life always happens.

2) Automate contributions like it’s your job (because it kinda is)

Regular investing works partly because it removes decision fatigue. Your future self shouldn’t depend on your

current self having a productive day and a calm nervous system.

Automatic investing also turns volatility into a feature: you buy more shares when prices are down and fewer

when prices are up. That’s not a hack; it’s a habit.

3) Diversify so one headline can’t ruin your week

Broad diversification (often through low-cost index funds or diversified ETFs) is the grown-up version of not

putting all your eggs in one basket. If you concentrate too much in one stock, sector, or trendy theme, you

increase the odds that the “best time to invest” turns into “the best time to learn a painful lesson.”

4) Rebalance with rules, not moods

Rebalancing is how you keep your risk from quietly drifting. When stocks surge, your portfolio can become more

aggressive than you intended. When stocks drop, fear can tempt you to “reduce risk” at the exact wrong moment.

A simple calendar-based rebalance (or threshold rules) can keep you honest.

5) Create a “panic protocol” before you need it

When the market drops, decide in advance what you will do:

- Keep contributions running.

- Don’t check your portfolio 17 times a day.

- Revisit your time horizon and asset allocation.

- If you must act, rebalancedon’t react.

This is not about pretending volatility doesn’t exist. It’s about refusing to turn volatility into self-sabotage.

So… What’s the Best Time to Invest?

The best time to invest is when you can commit to a long-term planbecause the real edge isn’t predicting next

month. The real edge is staying invested long enough for compounding to do its slow, slightly boring, extremely

powerful thing.

If you’re still accumulating wealth, rough markets aren’t automatically bad news. They can be the years you

buy future returns at a discount. If you’re closer to needing the money, the “best time” becomes less about

maximizing returns and more about matching risk to your timeline.

Either way, the common sense answer is surprisingly consistent: get invested, stay invested, and keep it

realistic.

Real-World Experiences: Lessons That Stick (About )

To make this topic feel less like theory and more like life, here are a few “seen-it-a-million-times” scenarios

that capture how the best time to invest usually plays out. These are composite storiescommon patterns, not

one specific personbecause investing mistakes are wildly unoriginal.

Experience #1: “I’m Waiting for the Dip” Becomes a Multi-Year Hobby

Someone decides the market looks “too high,” so they park cash in a savings account and promise themselves they’ll

invest after the next big pullback. The pullback arrives… but it’s attached to terrifying headlines. Instead of buying,

they wait for “more clarity.” Then the rebound happens quickly, and now the market feels high again. The cycle repeats

until the person is effectively timing the market by doing nothing.

The lesson: waiting feels safe, but it can quietly turn into the riskiest plan of allbecause the biggest risk in long-term

investing is never starting.

Experience #2: The “I Bought at the Worst Time” Investor Who Kept Going Anyway

Another investor starts a monthly contribution right before a nasty stretch. For a while, their account balance looks like

it’s auditioning for a sad movie. But they keep contributing because it’s automated and tied to a goal (retirement, a future

home down payment, financial independencepick your motivation).

Years later, something interesting happens: those early contributions, purchased at lower prices, become the foundation of

the portfolio’s growth. They don’t remember the exact week they started. They remember that they didn’t quit. That’s the point.

Experience #3: The “I’ll Get Back In When Things Calm Down” Trap

Some investors sell during a downturn to “protect what’s left,” planning to buy back in later. The problem is that “later” rarely

feels safe. Markets often recover while news is still gloomy, and the investor waits for a feel-good headline that arrives after prices

have already moved.

The lesson: the market tends to reward patience, not comfort. If your strategy requires you to feel calm to invest, you’ll invest at the

most expensive momentsbecause calm usually shows up after the recovery.

Experience #4: The Quiet Power of Boring Consistency

The most successful long-term investors are often the least dramatic. They set contributions, diversify, rebalance occasionally, and focus on

their savings rate. They treat volatility like weather: annoying, sometimes extreme, but not something you can negotiate with.

They also don’t confuse “best time to invest” with “best time to check your portfolio.” (Spoiler: the best time to check your portfolio is not

every time your phone buzzes.)

Conclusion

If you want the most common-sense answer to the best time to invest, it’s this: the best time is when you can start and keep going.

You can’t control market cycles, but you can control your contributions, your diversification, your costs, and your behavior. That’s where the

real advantage lives.

Start with a plan that matches your goals. Automate it. Diversify it. And when the market throws a tantrumas it eventually willremember:

the goal isn’t to avoid every scary moment. The goal is to still be invested when the better moments arrive.