Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Gateway Actually Is (and When It Shows Up)

- “Boots on the Moon” Is a Surface Problem, Not an Orbit Real-Estate Problem

- How Gateway Can Actually Slow the First Landings Down

- So Why Build Gateway At All?

- Gateway’s Best-Case Role: Making Later Landings Less Fragile

- Gateway’s Worst-Case Role: A Detour That Becomes the Destination

- What Would Actually Help Put Boots on the Moon Sooner?

- Conclusion: Gateway Isn’t the Key to the First Footprints

- Experience Notes: What Space Programs Teach Us About “Extra Infrastructure”

If you’re imagining NASA’s Lunar Gateway as the front porch that finally gets astronauts back inside the Moon,

you’re going to be disappointed. Gateway is real. It’s ambitious. It’s also showing up fashionably late to the

“boots on the Moon” partylike the friend who texts “On my way!” after the group photo is already posted.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Gateway isn’t what puts humans on the lunar surface again. The spacecraft that

launch, the landers that actually land, and the suits that let people work on the surface do that. Gateway is

better described as an investment in what comes after the first few landings: sustainability, flexibility, a

bigger operating “neighborhood” around the Moon, and practice for deep-space living.

So when someone says, “NASA’s Lunar Gateway won’t help put boots on the Moon,” they’re mostly rightat least

for the first return-to-the-surface missions. But the more interesting question is why NASA keeps building it

anyway, and what we gain (or risk losing) by turning a direct trip into a multi-stop itinerary.

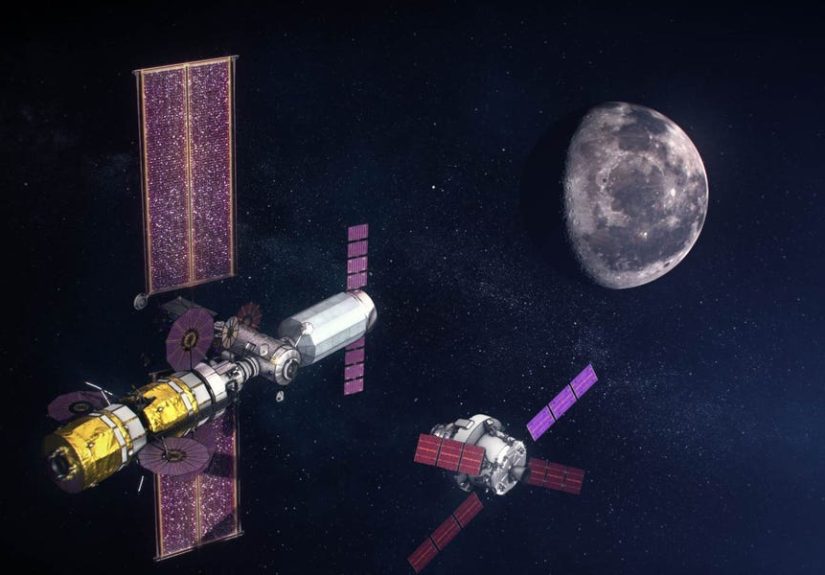

What Gateway Actually Is (and When It Shows Up)

Gateway is a small, human-tended space station intended to orbit the Moon in a special path called a

near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO). Think of NRHO as the Moon’s “good lighting” orbit:

it offers long lines of sight back to Earth, stable geometry for communications, and favorable access to the

lunar south pole region over time.

The starter kit: PPE + HALO

The first version of Gateway begins with two main elements launched together: the

Power and Propulsion Element (PPE) and HALO (Habitation and Logistics Outpost).

PPE provides power and the ability to maneuver the outpost; HALO provides early living and working volume plus

docking ports. The plan is for them to launch together on a commercial rocket and then cruise to lunar orbit.

Notably, Gateway isn’t positioned as “step one” for a near-term lunar landing. NASA’s current plan is for the

first crewed entry into Gateway to occur on Artemis IV, not the first landing mission. In other

words, Gateway is designed to support later lunar surface expeditions, not to unlock the first one.

NRHO: the orbit that makes engineers smile and mission planners sweat less

NRHO is part of why Gateway is attractive on paper: it reduces the amount of propellant needed for long-term

station-keeping compared with lower lunar orbits, offers good communications geometry, and provides a useful

staging region that repeatedly “leans” toward the lunar poles. It’s a clever choice for an outpost meant to

last years and host a variety of visiting vehicles.

But “clever orbit” is not the same as “required for a landing.” You can rendezvous in lunar orbit without a

station. Apollo did. Artemis can, too. Gateway’s orbit optimizes a long-term campaign; it doesn’t magically

shorten the path to the first set of footprints.

“Boots on the Moon” Is a Surface Problem, Not an Orbit Real-Estate Problem

To land astronauts on the Moon, you need three things to align: a ride to lunar orbit, a lander capable of

descending and ascending, and surface systems (spacesuits, life support, power, comms, tools) that let humans

operate safely.

Gateway doesn’t replace any of those. It’s not a lander. It’s not a launch vehicle. It’s not a spacesuit.

It’s infrastructure that becomes useful once you have frequent traffic, multiple destinations, and the

operational complexity that comes with a sustained presence.

Artemis III doesn’t “need a station” to do the core job

NASA’s Artemis III concept centers on getting a crewed spacecraft to lunar orbit and transferring two crew

members into a separate Human Landing System vehicle for descent to the surface and back.

That rendezvous can happen without a station in the middlebecause the rendezvous is between spacecraft, not

between spacecraft and real estate.

In fact, NASA has previously stated that Gateway is not mandatory for initial lunar landings, explicitly taking

it off the “critical path” for getting astronauts to the Moon early in the program. That architectural choice

matters: it’s a recognition that the fastest route to the surface is usually the simplest one.

Gateway arrives later because the early bottlenecks are elsewhere

The critical path for “boots on the Moon” tends to be dominated by development, integration, and testing of

human-rated systems: heat shields and life support for crew vehicles, the lander’s ability to perform complex

missions, and spacesuits that function reliably in the lunar south pole environment. A station in lunar orbit

doesn’t solve those. At best, it helps after those pieces work.

How Gateway Can Actually Slow the First Landings Down

A space station sounds like a helpful pit stopuntil you tally up what a pit stop costs in deep space.

Every extra major element in the architecture adds:

- More launches that must happen on time and work the first time

- More docking events (each one a complex, safety-critical operation)

- More mission rules and cross-program handoffs to coordinate

- More ways to slip the schedule when any component is late

Engineers love redundancy. Schedules do not.

Docking is not free, and “extra docking” is not extra fun

A direct rendezvous between a crew vehicle and a lander is already demanding. If you require both spacecraft

to dock to a station, then undock, then dock to each other (or to multiple ports), you increase the number of

critical events. Each event needs validated software, trained crew procedures, compatible docking systems, and

contingency planning for what happens if something doesn’t latch, align, or pressurize on the first try.

Gateway’s defenders will correctly note that docking is routine in low Earth orbit. But in lunar orbit, you

don’t get the same safety net: faster return timelines are harder, communications are different, and rescue

options are limited. Adding complexity before you’ve built cadence is like adding an extra ingredient to a

recipe you’ve never cookedthen serving it at a dinner party.

Integrated missions multiply risk across programs

Gateway-based missions pull together a long list of moving parts: a heavy-lift launch, a crew capsule,

a station element, a lander, and often international and commercial components. A Government Accountability

Office review has highlighted program-level risks (including mass management) and the multi-organization

complexity tied to the first Gateway landing mission. When everything must arrive and work together, “late”

becomes contagious.

So Why Build Gateway At All?

If Gateway isn’t the fast pass to the first footprints, why does NASA keep building it? Because NASA isn’t

only chasing a single landing. The Artemis vision is a long-term campaign: repeated lunar expeditions, science

in lunar orbit, technology demonstrations, and a bridge toward Mars-class deep space operations.

1) It’s a logistics and operations hub for later missions

Once you have multiple landing sites, multiple lander providers, cargo deliveries, and longer surface stays,

an orbital outpost becomes more valuable. Gateway can serve as:

- A place to stage and check out landers between missions

- A communications relay for surface assets (especially for polar regions)

- A platform for science in lunar orbit that complements surface science

- A “meet-up point” that supports reusability and a broader lunar transportation network

2) It’s a deep-space living lab, not just a lunar accessory

Gateway is meant to be inhabited in a harsher radiation and thermal environment than low Earth orbit. That

experienceoperating life support, doing maintenance, living and working with longer resupply linesdirectly

supports “Moon to Mars” goals. NASA’s own descriptions emphasize Gateway as a technology and habitation testbed

for deep space.

3) It keeps international partnerships meaningfully integrated

Artemis is structured around international collaboration. Gateway provides a clear place for partners to

contribute major hardware and capabilities. That’s not just diplomacy; it’s program resilience. When partners

invest real modules and systems, they become stakeholders in the long-term campaignand that can stabilize

political support over the long haul.

Cynically, you could call this “coalition management.” Practically, it’s how you build a multi-decade program

in a world where budgets and administrations change faster than rockets get certified.

Gateway’s Best-Case Role: Making Later Landings Less Fragile

In the best case, Gateway doesn’t speed up the first landingit de-risks the decade after it. Here’s

what “good” looks like:

-

More mission flexibility: If the lander arrives early, it can wait at Gateway. If Orion’s

schedule shifts, you may have a safe operating node already in orbit. -

Better surface support: Gateway can host communications gear, spare parts, and payloads that

improve surface mission productivity without forcing everything into one launch. -

Richer science: A lunar orbit outpost can support experiments that benefit from long, stable

baselines and deep-space exposure.

Gateway is most compelling when you’re not doing a single heroic landing, but running a lunar “railway” of

repeated sorties and cargo deliveriesbuilding toward something like a lunar base camp.

Gateway’s Worst-Case Role: A Detour That Becomes the Destination

The nightmare scenario isn’t that Gateway fails technically. It’s that it succeeds technically while stealing

oxygenbudget, attention, schedule marginfrom the things that actually touch the Moon.

If a program spends years perfecting the orbital outpost while landers and surface systems slip, you can end up

with a stunning piece of infrastructure and no reliable way to use it for what the public cares about:

astronauts walking on the surface, doing science, and returning safely.

A lunar space station is not a consolation prize for a delayed lunar landingunless you let it become one.

What Would Actually Help Put Boots on the Moon Sooner?

If the goal is “boots on the Moon” on a tighter timeline, the most helpful moves are boring in the best way:

they attack the real bottlenecks.

Focus areas that matter more than Gateway for near-term landings

-

Human Landing System readiness: Demonstrate the full mission profilerendezvous, descent,

ascent, and safe returnrepeatedly and predictably. -

Spacesuits and surface mobility: Lunar south pole operations are unforgiving: lighting,

temperature, dust, terrain. Suit reliability is mission reliability. -

Flight rate and learning curve: Cadence reduces risk. The faster you can safely fly, the more

you learn, and the less every mission feels like a once-in-a-lifetime stunt. -

Integration discipline: Complex programs fail in the seams. Testing interfaces earlyand

obsessing over those seamsbeats heroic “we’ll figure it out in flight” optimism.

Gateway can be a powerful asset once these pieces are in place. But Gateway can’t substitute for them, and it

can’t pull them forward by itself.

Conclusion: Gateway Isn’t the Key to the First Footprints

NASA’s Lunar Gateway is not a ladder that helps astronauts climb down to the Moon. It’s more like a workshop

you build once you already know how to get to the job site. The first set of Artemis lunar landings can happen

without it, and the program has treated Gateway as a later-phase enabler rather than an initial requirement.

The strongest argument against Gateway isn’t that it’s useless. It’s that it’s easy to confuse “impressive

infrastructure” with “mission-critical capability.” If the public wants boots on the Moon, the real story is

landers, suits, and flight-ready systemsnot an orbital waypoint that arrives after the first big milestone.

The strongest argument for Gateway is also simple: if Artemis is meant to become routine instead of symbolic,

a reusable outpost in lunar orbit could make the entire architecture more flexible and sustainableafter

the surface-return hurdle is cleared.

So yes: Gateway won’t help put boots on the Moonat least not the first pair. But it might help keep the boots

coming back, year after year, when the goal shifts from “plant a flag” to “build a presence.”

Experience Notes: What Space Programs Teach Us About “Extra Infrastructure”

Space exploration has a long history of building the “support system” firstsometimes wisely, sometimes

accidentally. The International Space Station is the obvious example: it took years of launches, assembly

flights, and international coordination before it became the orbiting laboratory most people picture today.

Early ISS missions weren’t glamorous; they were about making sure the basics worked: power, docking, life

support, and maintenance in a place where a hardware store run is not an option. That experience matters

because it shows what a space station is really for. It’s not the headline. It’s the rhythm.

Gateway is trying to borrow that lesson for the Moon: create a repeatable operating environment where crews

can practice deep-space procedures, fix things, test new systems, and host visiting spacecraft without turning

every mission into a do-or-die sprint. In the “space program lived experience” categorymeaning what decades of

missions reveal through hard-earned operationsstations tend to pay off when you fly often enough to learn.

Cadence turns novelty into normal.

But those same decades also teach the cautionary lesson: infrastructure can become a magnet for time and money.

Once a big station is on the books, it needs launches, logistics, upgrades, and endless engineering attention.

That’s not a moral failure; it’s physics plus paperwork. The risk is that everyone starts optimizing for the

station’s needs rather than the original mission’s goal. You’ve seen this pattern in major programs where the

“support element” becomes the center of gravityand suddenly the tail is wagging the lunar dog.

There’s also the psychological experience of complex mission design: every added stop feels comforting on a

diagram. More nodes. More options. More arrows. Then the first time you run a full mission rehearsal, the

arrows turn into meetings, interfaces, schedules, and “one more test we absolutely need.” A direct lunar

mission is already complex; a station-based architecture is a complex mission plus a permanent apartment that

needs utilities. The joke in engineering circles is that space is hardthen you add humansand then you add a

schedule. Gateway adds a schedule all by itself.

The best operational “experience” takeaway is this: Gateway should be treated like a force multiplier, not a

prerequisite. Fly the simplest path to prove you can land, then let the outpost amplify what you can do next:

longer stays, more surface sorties, more science, more international participation. If you reverse that order,

you risk building the nicest waiting room in the solar system while the ride to the destination keeps getting

rescheduled.