Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Exactly Is a Magnetar?

- New Discoveries: Magnetars Keep Leveling Up

- FRBs, Bursts, and the Magnetar Connection

- Why Magnetars Are Even More Hardcore Than Their Reputation

- What Magnetars Teach Us About the Universe

- of Cosmic “Experience”: What It’s Like to Live with Magnetars (From a Safe Distance)

- Wrapping It Up: Hardcore Stars, Softer Humans

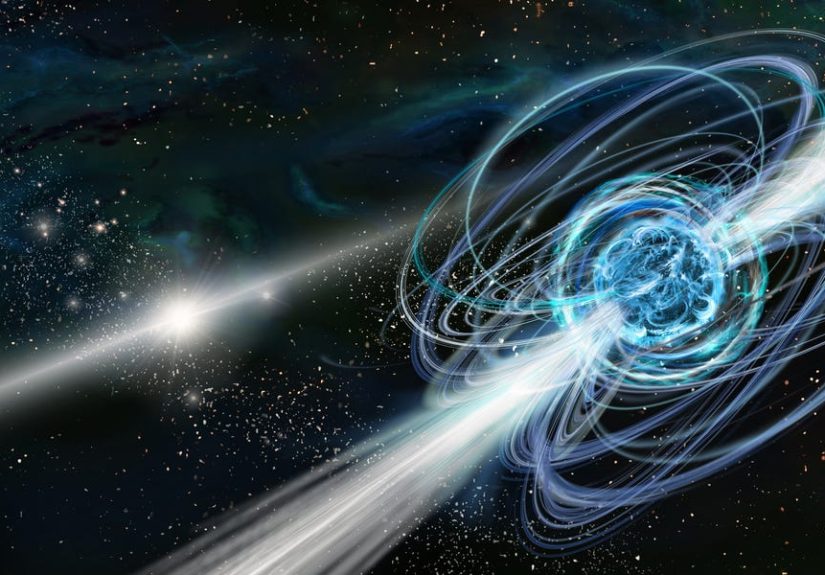

If black holes are the drama queens of the cosmos, magnetars are the quiet punks in the corner who could casually rip your credit card data from halfway to the Moon. These ultra-magnetized neutron stars were already extreme. But new observations keep forcing astronomers to rewrite just how wild, weird, and downright hardcore magnetars really are.

What Exactly Is a Magnetar?

Start with a massive starabout 10 to 25 times the mass of the Sun. Let it live fast, burn hot, and die in a spectacular supernova. What’s left behind is a neutron star: a collapsed core only about 12–20 kilometers across, yet holding more mass than the Sun.

Now take a small fraction of those neutron stars and give them the most ridiculous magnetic fields in the universe. That’s a magnetar: a neutron star whose magnetic field is about a thousand times stronger than that of a typical neutron star and roughly a trillion times stronger than Earth’s field.

Density That Laughs at Your Intuition

The density inside a magnetar is so high that a teaspoon of magnetar matter would weigh hundreds of millions of tons on Earth. You could park entire skyscrapers on that teaspoonif they weren’t instantly vaporized by the environment first.

That density means gravity is insane, too. The surface escape velocity approaches half the speed of light. If you could stand on a magnetar (you can’t), taking a step would be less of a “walk” and more of a very short “life choice.”

Magnetic Fields That Break Chemistry

Magnetars reach magnetic field strengths of about 1010 to 1011 tesla. For comparison, Earth’s field is around 30–60 microteslas, and a strong neodymium fridge magnet is about 1 tesla.

In a magnetar’s vicinity, those fields are so intense they would literally distort the electron clouds in atoms. At distances of around 1,000 kilometers, chemistry as we know it stops working. You don’t just erase hard drives; you erase matter’s ability to behave normally at all.

Already hardcore, right? But the latest research says: actually, you’ve been underestimating them.

New Discoveries: Magnetars Keep Leveling Up

A Runaway Magnetar That Breaks the Origin Story

For years, the standard story was simple: magnetars are born from supernova explosions. But the Hubble Space Telescope recently helped uncover a magnetar that appears to have a very different backstory. SGR 0501+4516, a magnetar zipping through the Milky Way, seems to be a runaway object, traveling from an unknown birthplace and showing signs it might not have formed in a “classic” supernova at all.

This roaming magnetar is like the kid who shows up halfway through the movie with a mysterious past and way more power than anyone expected. If some magnetars aren’t born in standard supernovae, there may be alternative formation channelssuch as stellar mergers or other exotic core-collapse scenarioscreating ultra-magnetized neutron stars in ways we’re only starting to understand.

Polarized X-Rays Reveal Twisted Magnetic Geometry

Another big leap forward comes from NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE). IXPE doesn’t just see X-raysit measures their polarization, which tells astronomers about the geometry and structure of the magnetic fields producing them.

Recent IXPE observations of several magnetars, including 1E 2259+586, show highly polarized X-ray emissionmuch more structured than many models predicted. This suggests magnetar magnetic fields are not just simple dipoles like “giant bar magnets” but a tangled mess of twisted field lines and complex configurations threading through and above the star.

In other words, magnetars don’t just have strong fields; they have weirdly organized strong fields, with twisted magnetic “tori” and hotspots that can store and suddenly release enormous amounts of energy in the form of X-ray and gamma-ray bursts.

Magnetars vs. the Laws of Brightness

Neutron stars are already luminous in X-rays, but some systems are so bright they seem to challenge long-held limits in astrophysics. Ultraluminous X-ray sources like M82 X-2 shine millions of times brighter than the Sun. Observations with NASA’s NuSTAR telescope show that at least some of these systems involve highly magnetized neutron stars whose magnetic fields help them funnel and supercharge matter onto their surfaces, pushing brightness levels beyond what was once considered the “Eddington limit” for stable radiation.

While not every ultraluminous X-ray source is a magnetar, these observations reveal that strong magnetic fields allow neutron stars to cheat what used to be thought of as fundamental brightness rules. Magnetars, with fields even stronger than typical neutron stars, may be the ultimate rule-breakers in this category.

FRBs, Bursts, and the Magnetar Connection

Fast radio bursts (FRBs) are one of astronomy’s biggest modern mysteries: millisecond-long flashes of radio light that release more energy in that instant than the Sun emits in days. They seem to come from all over the sky and from distant galaxies.

The leading suspect behind at least some FRBs? Magnetarsspecifically, young or highly active ones with unstable magnetic fields.

X-Ray Bursts in Sync with FRB-Like Radio Flashes

In 2020, a magnetar in our own galaxy, SGR 1935+2154, produced a bright radio burst remarkably similar to an FRB, accompanied by high-energy X-ray emission. Observations like these, along with later work, show that magnetars can produce FRB-like events.

More recently, long-term radio monitoring of magnetar XTE J1810–197 uncovered tens of thousands of individual radio pulses, spanning a wide range of energies and frequencies. This enormous dataset helps researchers explore how the magnetic environment and crustal stresses in a magnetar may scale up from “ordinary” pulses to rare, extreme outbursts that look like FRBs when observed from far away.

Pinpointing the Brightest FRBs with JWST

Fast forward to an FRB with the sci-fi-sounding name FRB 20250316A, one of the brightest ever recorded. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers traced this burst back to a specific region in a nearby galaxy and identified stars likely linked to the burst’s progenitora massive, evolved star possibly associated with a neutron star or magnetar companion.

These observations don’t just say “magnetars might be involved.” They show that FRBs happen in environments where magnetars should form, especially through massive stars or stellar mergers in metal-rich galaxies.

We used to wonder if magnetars could produce FRBs. Now the question is shifting to: how many of the FRBs in the sky are magnetars throwing giant magnetic tantrums?

Why Magnetars Are Even More Hardcore Than Their Reputation

They Warp Space, Time, and Physics Textbooks

Magnetars already sat at the intersection of strong gravity, nuclear physics, and quantum electrodynamics. Their magnetic fields may be strong enough to push matter into exotic quantum regimes where the vacuum itself behaves differentlywhat physicists call “quantum electrodynamic vacuum polarization.”

IXPE’s polarization studies, coupled with data from NICER and XMM-Newton, are letting scientists probe these crazy regimes directly for the first time, using X-rays as tracers of how light travels through ultra-strong magnetic fields.

They Have Short but Furious Lives

The active life of a magnetara period when it’s blasting out high-energy radiation and burstsis probably only about 10,000 years. After that, the magnetic field decays, and the star becomes much quieter.

That means the few dozen magnetars we’ve identified are likely just the tip of a very large, very dark iceberg. Models suggest our galaxy might contain millions of older, “retired” magnetars, now masquerading as ordinary neutron stars.

So the cosmos may be littered with ghost magnetarsonce-furious beasts now quietly coasting through space, their wild days long behind them.

They Refuse to Fit in a Single Box

Some magnetars behave like pulsars (those neatly ticking neutron stars that beam radio waves like lighthouses). Others flip between “radio-loud” and “radio-quiet” phases. Some show sudden glitches in their rotation, followed by bursts or flares, as if their crust cracked under magnetic stress.

Instead of a tidy category, magnetars look more like a dynamic spectrum of behaviors, driven by internal magnetic stresses, crustal fractures, and changing magnetospheric configurations. The more we observe, the harder it is to draw a line between “ordinary” neutron stars, pulsars, and magnetars. They might be different faces of the same underlying physics, just in more or less extreme magnetic moods.

What Magnetars Teach Us About the Universe

Beyond the spectacle, magnetars are powerful astrophysical laboratories:

- Testing extreme physics: They let us explore matter at nuclear density and fields where quantum theories of light and vacuum can be tested.

- Tracing stellar evolution: Their origins reveal how massive stars live, die, and sometimes merge, especially in metal-rich, star-forming galaxies.

- Probing galaxies with FRBs: FRBs likely powered by magnetars act as cosmic flashbulbs, illuminating the gas between galaxies and helping measure cosmic structures.

The punchline: the tougher we make our theories to explain magnetars, the more these stars respond with, “Nice try, here’s a new kind of burst you didn’t predict.”

of Cosmic “Experience”: What It’s Like to Live with Magnetars (From a Safe Distance)

Most of us will never get closer to a magnetar than a telescope image or a space-telescope press releaseand that’s honestly for the best. But we can still talk about the “experience” of magnetars in three ways: what it’s like for astronomers who study them, what it would feel like (in theory) to encounter one up close, and how they change our experience of the night sky.

Life as a Magnetar Astronomer

If you work on magnetars, your job is a mix of patience and panic. For months, a magnetar might sit there, doing very little. You monitor its X-ray emission, you track its spin rate, you write calm, careful papers. Then one day it erupts: a bright burst of X-rays, maybe a gamma-ray flare, or a sudden swarm of radio pulses. Instruments like Chandra, NICER, IXPE, and ground-based radio telescopes scramble to pivot and observe.

Teams coordinate across time zones; data floods in. Within hours to days, you’re comparing spectra, timing, polarization, and pulse shapes, trying to understand what just happened inside an object smaller than a city but more massive than the Sun. Did the crust crack? Did the magnetic field rearrange itself? Did we just witness a baby FRB event from our own galaxy?

The emotional experience is a roller coaster of “nothing, nothing, nothing… EVERYTHING!” Magnetars are like that friend who never textsuntil they send 47 unhinged messages in five seconds.

Imagining a Close Encounter (Don’t Try This at Home)

Now imagine, purely in thought experiment territory, approaching a magnetar. You would never get remotely close in reality; spacecraft, electronics, and biological matter would fail long before you glimpsed the surface. But conceptually:

- First, your instruments would notice insanely strong X-ray and gamma-ray fluxes long before your eyes saw anything unusual.

- Your navigation systems and onboard magnets would behave strangely as the magnetar’s field dominated your local environment.

- At closer distances, atomic structures themselves would be distorted. Chemical bondsthe stuff that makes up you, your ship, your snackswould stop behaving correctly.

It wouldn’t feel like “standing near a big magnet.” It would feel like reality itself was glitching at the level of matter and light. Magnetars are less like giant magnets and more like localized “physics anomalies” cruising through the galaxy.

How Magnetars Change Our View of the Night Sky

From Earth’s surface, magnetars don’t stand out to the naked eye. No brilliant neon star labeled “DO NOT TOUCH.” Yet they dominate the high-energy sky seen by X-ray and gamma-ray observatories. Soft gamma repeaters and anomalous X-ray pulsarsmany of which turned out to be magnetarswere first recognized by their bursts, not by a pretty visible-light picture.

For modern astronomy students, learning about magnetars is often the moment you realize just how far beyond “normal” stars the universe goes. Planetary systems, main-sequence stars, even red giants feel almost cozy and familiar by comparison. Once you’ve wrapped your head around a teaspoon of matter weighing a mountain, or a magnetic field that shreds chemistry, you can’t look at the sky quite the same way again.

In short, magnetars deepen our sense of cosmic awe. They’re reminders that the universe is not tuned for human comfort; it’s tuned for physics, and sometimes physics produces objects that make our boldest sci-fi ideas look tame.

Wrapping It Up: Hardcore Stars, Softer Humans

Magnetars started as a theoretical explanation for weird gamma-ray bursts. In just a few decades, they’ve become one of the most fascinating, multi-messenger laboratories in the universe. We now know they’re:

- Insanely dense and magnetic, with fields powerful enough to disrupt matter and light.

- More diverse in origin than we thought, possibly born not only in supernovae but also in exotic stellar mergers and runaway scenarios.

- Key suspects behind at least some fast radio bursts, linking high-energy and radio astronomy in surprising ways.

- Rule-benders in terms of brightness, pushing neutron stars to luminosities that once seemed impossible.

Every new magnetar discovered, every fresh burst observed, is another reminder that the universe is far more hardcore than we usually give it credit for. And magnetars? They’re leading that chargespinning slowly, flaring violently, and daring us to keep up.