Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Was Actually Discovered?

- Why This Discovery Matters

- Is This Wasp Dangerous to People, Pets, or Homes?

- What About TreesAre Oaks in Trouble?

- How Non-Native Parasitoids Typically Arrive

- How Scientists Found It: Why This Wasn’t an Accident

- What Homeowners, Gardeners, and Arborists Should Do

- Three Real-World Scenarios

- Myths vs Facts

- What We Still Don’t Know Yet

- Extended Experience Section: from the Field

- Conclusion

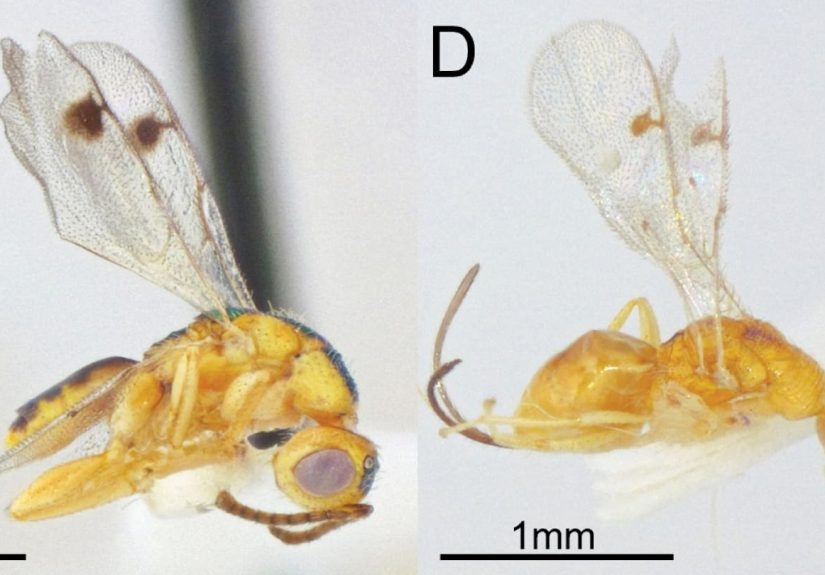

Tiny wasps are having a big moment. In 2025, researchers reported that a European parasitic wasp complex,

Bootanomyia dorsalis, has now been documented in the United Statesmarking a major update for

North American insect records and a fresh reminder that biological invasions do not always arrive with

dramatic fanfare. Sometimes, they arrive smaller than a sesame seed.

If you’re picturing a horror-movie swarm, take a breath. This isn’t that. These are parasitoid wasps tied to

oak gall ecosystems, and they are part of a dense web of insect-on-insect interactions. The real story is

ecological: how non-native species establish, how scientists detect them, and what gardeners, arborists,

and homeowners should do when they hear “invasive wasp” in a headline.

This guide breaks down what was found, why it matters, what risks are known (and still unknown), and how to respond

without panic, pesticide overreaction, or unnecessary tree drama.

What Was Actually Discovered?

The short version

Scientists documented Bootanomyia dorsalis in North America, including U.S. populations associated with oak

gall wasps. Evidence suggests multiple introductions rather than one single event. In other words: this was not one

hitchhiker; it may have been several rides, several routes, and possibly several timelines.

The longer, nerdier (but important) version

The research used integrative taxonomycombining morphology (physical traits) and genetics (including mitochondrial

markers)to confirm identities. Investigators found distinct eastern and western population patterns, consistent with

separate introductions. One population aligns with material linked to a known Palearctic host association in New York,

while western populations show a different pattern and little mitochondrial variation.

Translation: these wasps likely did not spread from one U.S. neighborhood outward in a neat ripple. They appear to have

entered through different pathways, then settled into local oak gall communities.

Why This Discovery Matters

1) It updates U.S. biodiversity records

First records matter. They change species checklists, risk models, and surveillance priorities. A new non-native parasitoid

in oak systems means agencies and researchers may need to refine monitoring and identification workflows, especially where

oak gall wasps are common.

2) It raises ecological questionsnot just taxonomic ones

Parasitoids can influence food webs in subtle ways. They may suppress certain hosts, compete with native parasitoids, or

shift timing in multi-species interactions. Because oak gall ecosystems are already complex, adding a non-native parasitoid

can have effects that are real but not immediately visible in your backyard.

3) It highlights the “quiet invasion” pattern

Invasive species aren’t always loud, obvious, or instantly destructive. Some settle in quietly, spread through trade and

plant movement, and only get detected when specialists do careful rearing and genetic work. This case is a textbook example

of why early detection and long-term surveillance matter.

Is This Wasp Dangerous to People, Pets, or Homes?

For most people, the practical risk is low. Parasitoid wasps in this ecological group are not house-damaging pests like

termites, and extension sources consistently describe many parasitoid wasps as harmless to humans. They are typically tiny,

focused on host insects, and not interested in stinging you during your Saturday tomato-check routine.

So no, this is not a “cancel your picnic forever” insect event. The concern is ecological balance, not human medical danger.

What About TreesAre Oaks in Trouble?

Oak galls often look alarming (they can resemble odd fruit, marbles, or spiky growths), but many extension resources note

that most oak galls do not seriously threaten overall tree health. Galls are part of a long-evolved interaction between oaks

and gall-forming wasps, and those galls themselves host entire communities of parasitoids, inquilines, predators, and microbes.

In plain English: weird bumps on oak leaves are often more “ecological apartment complex” than “tree death sentence.”

Tree stress depends on species, infestation intensity, weather, and overall health.

How Non-Native Parasitoids Typically Arrive

If you guessed “airline ticket under a fake name,” close. Federal research on interception records shows insect predators

and parasitoids are often transported unintentionally, with imported plants and plant products representing a major pathway.

The hitchhiker model is well established: tiny organisms move with trade, then establish where hosts and suitable climate exist.

That doesn’t mean every non-native parasitoid becomes a disaster. Some introduced natural enemies can help suppress pests.

But unintentional introductions are less controlled than intentional biological control programs, and that uncertainty is why

regulators and ecologists stay cautious.

How Scientists Found It: Why This Wasn’t an Accident

Large-scale sampling

Teams collected oak galls across regions and reared large numbers of parasitoids. This matters because rare or newly

introduced insects can be missed in casual sampling.

Morphology + genetics together

Appearance alone can be tricky in tiny wasps. Pairing structural traits with DNA makes identification stronger, especially

for species complexes and closely related lineages.

Cross-institution collaboration

University labs and taxonomic specialists compared material from different geographies, improving confidence that records

represented real introduction patterns rather than local anomalies.

What Homeowners, Gardeners, and Arborists Should Do

Do this

- Observe before acting: Not every gall or tiny wasp warrants treatment.

- Document suspicious finds: Clear photos, date, host plant, and location are useful.

- Report through proper channels: Local extension offices, state agriculture agencies, and vetted reporting platforms can triage observations.

- Reduce spread pathways: Be careful moving plant material across regions; buy from reputable domestic sources.

- Support beneficial insects: Diverse flowering habitat and reduced broad-spectrum pesticide use can stabilize beneficial communities.

Don’t do this

- Don’t panic-spray: Broad insecticides can kill beneficials and worsen ecological imbalance.

- Don’t assume every wasp is harmful: Many parasitoids are allies in pest suppression.

- Don’t remove every gall on sight: In many cases, management is unnecessary and ecological costs can outweigh cosmetic benefits.

Three Real-World Scenarios

Scenario A: The suburban oak owner

You notice spherical galls on leaves and fear an infestation apocalypse. Best move: photograph, monitor, and consult extension guidance.

If the tree is otherwise vigorous, immediate chemical treatment is rarely the right first step.

Scenario B: The nursery manager

You source ornamental oaks and related plant material from multiple regions. Your best defense is prevention:

supplier vetting, incoming inspections, sanitation protocols, and staff training on unusual gall/parasitoid signs.

Scenario C: The city arborist

You manage hundreds of urban oaks. Build a data workflow: periodic surveys, geotagged observations, lab confirmation

for unusual finds, and communication templates that prevent public panic while promoting reporting accuracy.

Myths vs Facts

Myth: “Parasitic wasp” means danger to people.

Fact: In this context, “parasitic” refers to insect hosts, not humans.

Myth: Any non-native insect should be exterminated immediately.

Fact: Rapid response should be targeted and evidence-based, not blanket spraying.

Myth: Oak galls always mean your tree is dying.

Fact: Many oak galls are primarily aesthetic and not severe threats to tree health.

Myth: If it is tiny, it is insignificant.

Fact: Tiny parasitoids can reshape insect communities over time.

What We Still Don’t Know Yet

- How widely these lineages are already distributed across U.S. oak habitats.

- Which native parasitoids may be displaced, if any.

- Whether effects will remain subtle or become measurable at broader ecosystem scales.

- How climate shifts may influence establishment and spread over the next decade.

Good science here means disciplined patience: more surveys, better records, and fewer assumptions.

Extended Experience Section: from the Field

Over the past year, conversations with gardeners, extension volunteers, and municipal tree teams reveal the same pattern:

the moment people hear “new invasive wasp,” they picture immediate damage. Then they walk outside, inspect the nearest oak,

and discover something surprisingmost of what they thought was catastrophic is actually normal ecological complexity.

One Master Gardener in the Mid-Atlantic described a neighborhood workshop where residents brought in leaves covered with odd,

bead-like growths. At first glance, the room felt tense. Somebody joked that the tree had “chicken pox.” Another asked whether

the HOA should remove every oak before spring. But once the group reviewed basic gall biology, the mood changed from panic to curiosity.

People stopped saying “infection” and started saying “life cycle.” That vocabulary shift matters. It changes decisions.

A city forester in the Pacific Northwest shared a practical lesson: communication has to be specific. Generic warnings like

“watch for invasive insects” lead to overreporting and false alarms. Instead, his team used simple visual checklists:

host tree, gall type, approximate timing, and photo angles that help experts identify structures. Reports became fewer, but far better.

Better data meant faster triage and less wasted labor.

In a community garden setting, one coordinator noticed volunteers were squashing hornworms covered in white cocoons.

They believed those cocoons were “eggs of a worse pest.” After a short training session, volunteers learned those white structures

often indicate parasitoids already doing biological control. The following season, pest pressure looked lower in beds where beneficials

were protected and broad-spectrum sprays were reduced. Nobody claimed magic. But the result was a calmer, smarter IPM routine.

Another recurring theme: people trust what they can document. A homeowner in upstate New York started logging oak leaf observations

with date-stamped phone photos every two weeks. By the end of summer, she had a simple timeline showing when galls appeared, darkened,

and developed exit holes. That record helped an extension specialist reassure her that the tree’s canopy density and annual growth

were still strong. Instead of paying for unnecessary treatments, she invested in mulch rings, drought-watering during heat waves,

and pruning deadwood at the right time.

Researchers often say early detection is a team sport, and field experience supports that. The best results came from collaboration:

residents who observe, extension agents who interpret, labs that confirm, and local agencies that coordinate. Even digital tools helped.

Community members who posted careful observations to science platforms gave experts leads they might not have found quickly through formal

surveys alone.

The broader experience is this: fear shrinks when people understand process. Once you know that oak galls are habitats, parasitoids are

often beneficial, and non-native detection requires evidence, the story becomes less about “kill it now” and more about stewardship.

Monitor. Record. Report responsibly. Protect tree health fundamentals. And keep your sense of humorbecause nature has always been a bit

strange, long before the headlines caught up.

Conclusion

The first U.S. documentation of this parasitic wasp complex is an important scientific development, not a reason for public panic.

The right response is informed vigilance: accurate identification, careful reporting, and ecological management that avoids collateral

damage from overreaction. Invasive species management works best when it combines science, local observation, and practical restraint.

Tiny wasps, big lesson: good data beats loud assumptions every time.