Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The quick definition (and why “cords” is kind of a lie)

- Where they live: your larynx, aka the voice box

- What they’re made of: the “layer cake” that lets them vibrate

- How your vocal cords make sound (without tiny speakers)

- Their other jobs: breathing, swallowing, and “nope” reflexes

- What irritates or injures vocal cords

- Common vocal cord problems (and what they feel like)

- How doctors actually look at vocal cords

- Vocal hygiene: simple habits that protect your voice

- Mini FAQ

- Conclusion: your two tiny superhero folds

- Real-life experiences related to “What Are Your Vocal Cords?” (About )

Your vocal cords are the reason you can laugh, whisper secrets, belt out a chorus in the car, and say “I’m fine”

in a tone that clearly means “I’m not fine.” They’re small, fast, and surprisingly athleticworking every time you

talk, sing, cough, or even swallow. And despite the name, they aren’t actually “cords” like guitar strings.

(If they were, a lot more people would come with an optional carrying case.)

In medical terms, vocal cords are vocal folds: two flexible bands of tissue inside your

larynx (your “voice box”). They open to let you breathe, close to help protect your airway when you

swallow, and vibrate to create sound when air flows past them. That’s a lot of responsibility for something you

can’t even see in a mirror without special equipment.

The quick definition (and why “cords” is kind of a lie)

Your vocal cords (vocal folds) are two muscular folds covered with a slippery lining. When you breathe,

they separate so air can travel to your lungs. When you speak or sing, they move closer together and vibrate as

air passes through, creating sound waves that your throat, mouth, and nose shape into the voice people recognize as

“you.”

The “cords” nickname sticks because they’re paired and can be tightened or relaxed to change pitchkind of like

adjusting strings. But they’re more like two soft doors that can swing open, snap closed, and flutter in

controlled waves.

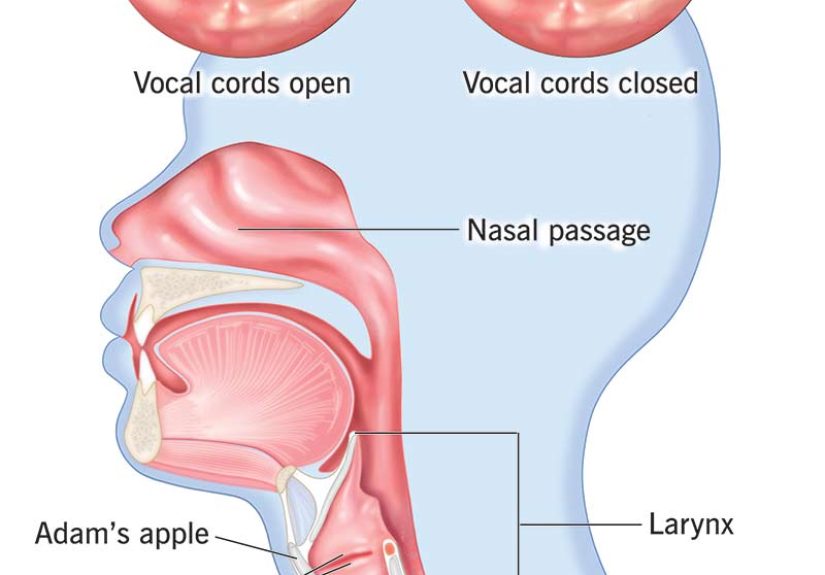

Where they live: your larynx, aka the voice box

Your vocal folds sit in your larynx, a short structure in your neck above your windpipe

(trachea). The larynx has three big jobs:

- Breathing: keeping the airway open so air can move in and out.

- Protection: closing up when you swallow so food and drink go down the right pipe.

- Voice: producing sound through vibration (phonation).

True vocal folds vs “false” vocal folds

If you’ve ever heard someone mention “false vocal cords,” they’re talking about vestibular folds.

They sit just above the true vocal folds (the ones that do most voice-making). False folds don’t

normally vibrate for everyday speech, but they can help with airway protection and sometimes get involved in

certain voice techniques (or in voice strain when the throat tries to “help” too much).

The moving parts: cartilage, muscles, and nerves

Vocal folds aren’t floating around on their ownthey’re anchored to laryngeal cartilages and moved by small,

precise muscles. Those muscles adjust:

- Position: bringing the folds together (closure) or apart (opening).

- Tension: tightening for higher pitch, relaxing for lower pitch.

- Length: subtly stretching or shortening the folds.

Nerves from your brain coordinate this like a high-speed group chat. If those nerve signals are disrupted, the

vocal folds may not move normallyone reason conditions like vocal cord paralysis can change the

sound and strength of the voice.

What they’re made of: the “layer cake” that lets them vibrate

Vocal folds work because they’re built like a specialized vibration system: a flexible cover over a supportive

core, anchored to muscle. Many medical references describe distinct layers that help explain how the folds can

vibrate smoothly while handling the stress of frequent use.

The cover, the cushion, and the muscle

Think of your vocal folds as a tiny, biologic trampoline:

- Outer lining (cover): a thin surface layer that stays moist and helps create smooth vibration.

-

Middle supportive layers (cushion/ligament): tissues with different firmness that guide how the

vibration wave travels. - Deep muscle (vocalis/thyroarytenoid): the “engine” that helps adjust tension and thickness.

This layered structure matters because voice isn’t just “air making noise.” It’s air + tissue physics + muscle

control + resonancebasically a science fair project you carry around all day.

How your vocal cords make sound (without tiny speakers)

Voice production is often explained as a teamwork chain: lungs provide air, vocal folds vibrate to create sound,

and the vocal tract shapes that sound into speech.

Step 1: Airflow from the lungs

When you decide to speak, your breathing system provides a steady stream of air. That air travels up the trachea

toward the larynx. If the vocal folds are brought close together, the passing airflow sets them into motion.

Step 2: Vibration + the mucosal wave

Vocal folds don’t flap randomlythey vibrate in a patterned way. A ripple called the mucosal wave

moves along the fold’s surface as it opens and closes rapidly. This is one reason healthy vocal folds can produce

a clear tone, while swelling or dryness can make the voice sound rough or breathy.

Step 3: Pitch, loudness, and tone color

Your brain tweaks the vocal folds and airflow to change how you sound:

-

Pitch (how high/low): influenced by fold length, tension, and thickness. Tight/long tends to

raise pitch; relaxed/thicker tends to lower it. - Loudness (volume): often increases with stronger airflow and firm, efficient vocal fold closure.

- Tone quality: shaped by how evenly the folds vibrate and how your throat/mouth/nose resonate.

That’s why “just talk louder” is not always good advicelouder can be produced efficiently, or it can be produced

by squeezing the throat like you’re trying to win an argument with gravity.

Step 4: Your mouth turns buzz into words

The sound created at the vocal folds is more like a raw buzz. Your tongue, lips, jaw, and soft palate turn that

buzz into consonants and vowels. Your nose and sinuses add resonance. In other words: your vocal folds make the

instrument sound; the rest of you plays the song.

Their other jobs: breathing, swallowing, and “nope” reflexes

Vocal folds aren’t just for chatting. They’re also part of your airway safety systemwhich is why the body takes

vocal fold problems seriously.

Breathing (opening wide)

During normal breathing, the vocal folds move apart so air flows freely. If the opening is reduced, breathing can

feel noisy or effortful. This is one reason airway symptoms with voice changes deserve medical attention.

Swallowing (closing fast)

When you swallow, structures in the throat coordinate to keep food and liquid out of the airway. Vocal fold

closure helps form a protective seal so what you eat goes toward your esophagus instead of your lungs.

Coughing and throat clearing (the bouncer function)

Coughing is a powerful protective reflex that uses vocal fold closure and pressure to blast irritants out of the

airway. But frequent throat clearing can also irritate the vocal foldslike repeatedly rubbing a small scrape and

expecting it to heal faster.

What irritates or injures vocal cords

Infections and inflammation (laryngitis)

Laryngitis is inflammation of the larynx, often from a viral infection, overuse, or irritation.

When vocal folds swell, they don’t vibrate as cleanly, so the voice becomes hoarse. Sometimes the voice temporarily

weakens or cuts out entirely.

Overuse and misuse (cheering, yelling, whispering)

Heavy voice use can strain the vocal folds, especially if you’re pushing volume or speaking for long stretches

without breaks (teachers, coaches, performers, customer service workersthis is your club). Yelling can slam the

folds together with excess force. And yes, whispering can also be stressful because it often encourages inefficient

airflow and throat tension.

Reflux, smoke, dry air, and allergies

Irritants that dry out or inflame the throat can affect voice quality. Examples include smoking, vaping aerosols,

chronic exposure to dust/chemicals, and reflux that irritates the larynx. Allergies and postnasal drip can lead to

throat clearing and swelling, which can snowball into ongoing hoarseness.

Common vocal cord problems (and what they feel like)

“Hoarse” can mean raspy, rough, weak, breathy, strained, lower than usual, or tiring to use. Different issues can

cause similar symptoms, which is why persistent voice changes shouldn’t be brushed off as “just a weird week.”

Nodules, polyps, and cysts

These are common noncancerous growths or changes on the vocal folds. They can disrupt vibration and closure,

leading to hoarseness and voice fatigue.

-

Vocal nodules: often described as callus-like changes from repeated strainfrequently seen in

people who use their voice heavily. - Vocal polyps: soft, blister-like growths that may follow heavy voice use or irritation.

-

Vocal cysts: sac-like lesions that can interfere with vibration and may not improve without

specialized care.

Treatment often starts with voice therapy (learning efficient voice habits) and reducing triggers.

Some cases may require medical or surgical management, especially if a lesion doesn’t improve.

Vocal cord paralysis

Vocal cord paralysis happens when nerve signals to the laryngeal muscles are disrupted, affecting how one or both

vocal folds move. People may notice a breathy voice, reduced volume, vocal fatigue, or choking/coughing with

liquids if airway protection is affected.

Muscle tension dysphonia and “tight throat” voice

Sometimes the vocal folds aren’t the only issuethe surrounding muscles squeeze too much, creating a strained,

tight, or effortful voice. This pattern is often addressed with skilled evaluation and targeted therapy to reduce

inefficient muscle patterns.

When hoarseness needs a real checkup

Many voice changes improve with rest and time, especially after a cold. But clinical guidelines emphasize that

hoarseness (dysphonia) that doesn’t resolve within about four weeks should be evaluated with a look

at the larynx, particularly if there are concerning symptoms. If you have trouble breathing, significant swallowing

difficulty, coughing blood, a neck lump, or persistent unexplained voice change, it’s time to get checked by a

clinicianpreferably an ENT (otolaryngologist).

How doctors actually look at vocal cords

Laryngoscopy in plain English

You can’t diagnose most vocal fold problems by guessing. That’s why clinicians use laryngoscopya

way to visualize the vocal folds. Sometimes it’s done with a small camera through the nose (flexible scope) or

through the mouth (rigid scope). It sounds dramatic, but it’s usually quick, and it gives real answers instead of

“maybe it’s reflux?”

Voice team: ENT + speech-language pathologist

Many voice clinics use a team approach: an ENT evaluates the larynx medically, and a

speech-language pathologist helps with voice function, technique, and recovery. For performers and

heavy voice users, learning efficient voice habits can be as important as treating the underlying irritation.

Vocal hygiene: simple habits that protect your voice

“Vocal hygiene” is basically the maintenance plan for your built-in instrument. The goal isn’t to never raise your

voice againit’s to help your vocal folds stay healthy, moist, and efficient.

Hydration + humidity

- Drink water regularly: hydration supports smoother vibration.

- Use humidity when air is dry: especially during winter heating or in air-conditioned spaces.

- Go easy on drying habits: smoking and irritant exposure can dry and inflame the larynx.

Smart loudness and “good” voice rest

- Avoid yelling contests: if you need volume, move closer or use amplification.

- Don’t “push through” hoarseness: it’s like running on a sprained anklepossible, but unwise.

- Limit whispering when irritated: it can encourage tension and inefficient airflow.

Warm-ups, breaks, and recovery after you’ve overdone it

Professional voice users often warm up gently, take breaks, and cool downbecause vocal folds respond well to

graded use. If you’ve had a big “concert night” or “sports game scream-fest,” treat your voice like you treated

your legs after an intense workout: rest, hydrate, and ease back in.

Reflux-friendly tweaks

If reflux symptoms are part of the picture, lifestyle changes (like timing meals and avoiding known triggers) may

help. Importantly, clinical guidance discourages treating isolated hoarseness with reflux meds unless reflux signs

and symptoms support that approachanother reason proper evaluation matters.

Mini FAQ

Can you “strengthen” your vocal cords?

You can improve how efficiently you use your voice. Voice therapy and good technique can reduce strain and make the

sound stronger without “bulking up” the folds. Think coordination, not biceps.

Are vocal cords the same as your Adam’s apple?

Not exactly. The Adam’s apple is the front of the thyroid cartilagepart of the larynx structure. The vocal folds

are inside the larynx, attached to cartilages that move as you speak and swallow.

Why does your voice sound weird on recordings?

Your voice reaches you through both air and vibration through your skull, which changes how you perceive it.

Recordings capture mostly the air-conducted soundso it can feel unfamiliar, even though everyone else thinks it

sounds normal.

Conclusion: your two tiny superhero folds

Your vocal cordsmore accurately, your vocal foldsare a pair of specialized tissues in the larynx that open for

breathing, close for swallowing safety, and vibrate to create the sound of your voice. Their layered structure and

precise muscle control let them shift pitch, volume, and tone in milliseconds. And because they’re both delicate

and hardworking, they can get irritated by infections, dryness, reflux, smoke, or repeated strain.

If your voice is hoarse for weeks instead of days, or if you have symptoms like breathing trouble or swallowing

problems, it’s worth getting your larynx evaluated. The good news: many voice issues improve with smart habits,

targeted therapy, and addressing the underlying causeso your vocal folds can get back to doing what they do best:

turning thoughts into sound.

Real-life experiences related to “What Are Your Vocal Cords?” (About )

People usually notice their vocal cords only when something changeskind of like how you don’t think about your

knees until you take the stairs after leg day. One of the most common experiences is the “morning voice.” You wake

up and sound lower, rougher, or slightly gravelly, then your voice clears after a few minutes of talking. This can

happen because tissues are a bit drier after hours of breathing at night, and because your voice “warms up” as your

breathing and muscle coordination become more active.

Another classic moment: cheering at a game or singing loudly at a concert, then waking up the next day with a voice

that sounds like it got replaced by a rusty door hinge. That’s often a sign of temporary irritation or swelling in

the vocal folds. The experience can be surprising because you might not feel painjust a voice that cracks, fades,

or tires quickly. People often describe needing extra effort to speak, as if their voice is “stuck” behind the

throat. That effort can lead to even more squeezing, which makes the sound worse, creating an annoying loop:

strained voice → more pushing → more strain.

Heavy voice users have their own recognizable patterns. Teachers and coaches sometimes notice their voice fades by

afternoon, especially during the first weeks of a busy season. They may feel like they’re always “projecting,”

which can push the vocal folds to collide harder and more often. Many learn that the best upgrade isn’t superhuman

lungsit’s strategy: using a microphone, facing the group instead of talking while writing on the board, building

in quiet activities, and taking short vocal breaks. When those changes work, the experience is almost magical:

the same amount of teaching, but far less hoarseness at the end of the day.

Some people experience hoarseness during or after a cold, and the voice can take longer to bounce back than the

sniffles. They might notice that speaking at a normal pitch feels uncomfortable, or that their voice “breaks” when

they try to go higher. This can happen because the vocal folds are still swollen or irritated even after other

symptoms improve. A common experience is discovering that whispering doesn’t feel like “rest”it can feel oddly

tiring, because the throat may tighten while trying to create a quiet sound.

Then there’s the experience of voice anxiety: you have an important presentation, and suddenly your throat feels

tight and your voice feels less reliable. Stress can change breathing patterns and muscle tension, which can affect

voice clarity and endurance. Many people find that slow breathing, gentle warm-ups (like easy humming), and sipping

water help the voice feel steadiernot because water is a magic potion, but because hydration and calm breathing

support more efficient vibration.

The shared takeaway from these everyday experiences is simple: vocal cords are responsive. When you treat them like

delicate tissues that do athletic workhydration, breaks, less shouting, less throat clearingthey often reward you

with a clearer, easier voice.