Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- CTE in Plain English

- What Causes CTE?

- Who Is at Risk?

- Symptoms: What CTE Can Look Like

- CTE vs. Concussion vs. Post-Concussion Symptoms

- How Is CTE Diagnosed?

- What Science Knows (and What It Doesn’t)

- Treatment: What Can Be Done?

- Prevention and Risk Reduction: The Practical Stuff That Actually Helps

- When to See a Doctor

- Big Picture: A Calm Take in a Loud Internet

- Experiences Related to CTE: What People Commonly Describe

- Conclusion

CTE (short for chronic traumatic encephalopathy) is one of those medical terms that sounds like it was invented by a committee that hates vowels. But the idea behind it is actually pretty simple: CTE is a progressive brain disease linked to long-term exposure to repeated head impacts. It’s most often discussed in connection with contact sports (think football, boxing, hockey) and sometimes military serviceany situation where the brain might get rattled again and again over time.

Here’s the tricky part (and why the topic gets so much attention): CTE can’t currently be diagnosed with certainty in living people. The definitive diagnosis still requires examining brain tissue after death. That means a lot of what you read online blends real science with guesswork, headlines, andlet’s be honestsome dramatic “WebMD energy.” This overview sticks to what researchers and major medical organizations broadly agree on, what’s still unknown, and what practical steps can reduce risk.

CTE in Plain English

CTE is considered a neurodegenerative disease, meaning it involves the gradual loss of healthy brain cells and brain function over time. Researchers classify it as a tauopathy, because an abnormal form of a protein called tau builds up in certain patterns in the brain. In CTE, tau deposits tend to appear in a distinctive wayoften around small blood vessels and in the folds of the brain (the “valleys” between the ridges).

Even if you never plan on memorizing the word “tauopathy,” the key takeaway is this: CTE is not “just a concussion.” It’s not the same as a short-term head injury. It’s a long-term disease process that may develop years or even decades after repeated head impacts.

What Causes CTE?

The best-supported risk factor for CTE is repetitive head impacts (RHI) over time. Importantly, these impacts can include:

- Concussions (head injuries that cause symptoms such as headache, dizziness, confusion, or memory issues)

- Subconcussive impacts (hits that don’t cause obvious concussion symptoms but still jolt the brain)

This is where the conversation often needs a reset. Many people assume CTE is caused by “a concussion or two.” But large public health organizations have emphasized that current evidence is stronger for long-term, repeated exposure than for isolated events. In other words, CTE is more about the accumulation of impacts than one “big hit.”

How repeated impacts might lead to long-term brain changes

Researchers are still mapping the exact chain reaction, but several mechanisms show up often in the scientific discussion:

- Abnormal tau buildup that spreads over time and interferes with nerve cell function

- Chronic inflammation in brain tissue

- Changes in blood vessels and the blood-brain barrier

- Loss of neurons in areas involved in thinking, mood, and behavior

None of this means that everyone who plays a contact sport will develop CTE. It does mean that reducing unnecessary head impacts is a smart movelike wearing sunscreen even if you don’t burn easily.

Who Is at Risk?

CTE has most commonly been identified in people with long histories of repetitive head impacts, including:

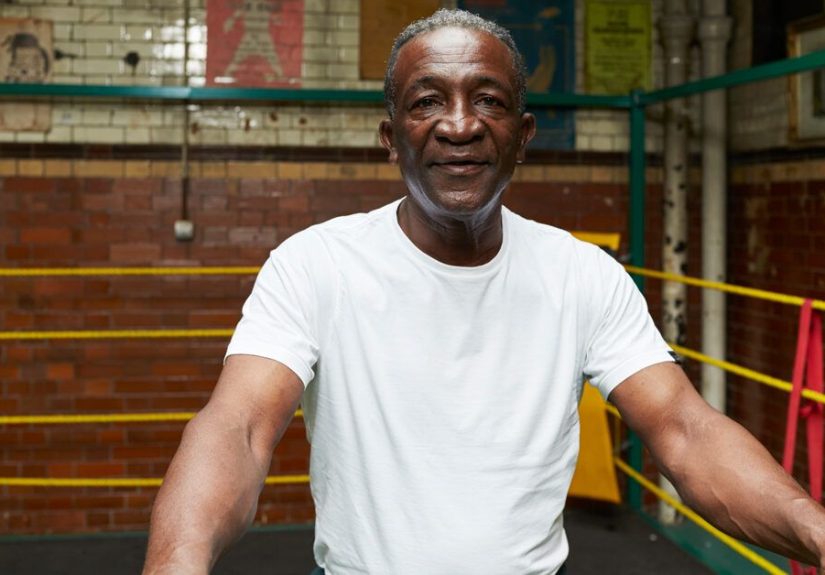

- Contact and collision sport athletes (football, boxing, ice hockey, rugby, and more)

- Some military veterans, especially those with repeated blast exposure or head trauma

- Others with repeated head impacts over time (for example, through certain occupations or frequent falls)

What about youth sports?

Youth sports are a huge part of the U.S. conversation about head impacts because brains are still developing, and because practice routines can create lots of repeated contact. Research comparing different versions of the same sport has found major differences in head impact exposure (for example, tackle versus non-tackle formats). That doesn’t automatically translate into “this kid will get CTE,” but it does reinforce a practical principle: less head contact is generally better, especially when it isn’t essential to learning the sport.

Symptoms: What CTE Can Look Like

CTE is associated with symptoms that may involve thinking, mood, behavior, and movement. Symptoms reported in people later found to have CTE have included:

- Memory problems and difficulty learning new information

- Confusion or disorientation

- Problems with judgment and decision-making

- Impulse control issues (doing things without thinking them through)

- Irritability, mood swings, anxiety, or depression

- Aggression or increased emotional reactivity

- Speech or balance problems in some cases

- Parkinsonism (movement symptoms like slowed movement or stiffness) in later stages for some people

One of the reasons CTE is so hard to study is that these symptoms are not unique to CTE. They can also occur with other conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, sleep problems, PTSD, Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurodegenerative diseases. That overlap makes it especially important not to “diagnose” someone based on a checklist from the internet.

When do symptoms start?

Symptoms are often described as appearing years or decades after the period of repeated head impacts. That time lag is part of what makes people feel blindsidedlike the brain kept receipts and decided to present the bill in middle age.

CTE vs. Concussion vs. Post-Concussion Symptoms

These terms get mixed together all the time, so let’s separate them cleanly:

Concussion

A concussion is a type of mild traumatic brain injury. It can cause short-term symptoms such as headache, dizziness, sensitivity to light, brain fog, or trouble concentrating. Most people recover, especially with proper rest and medical guidance.

Persistent post-concussion symptoms

Some people have symptoms that last longer than expected. These can include headaches, sleep issues, mood changes, and cognitive difficulties. Persistent symptoms can be real and seriousand still not be CTE.

CTE

CTE is a specific neurodegenerative disease linked to long-term repeated head impacts. It is currently confirmed by specific patterns in brain tissue, not by symptoms alone.

Bottom line: A concussion is an injury. CTE is a disease process. They’re related in the sense that repeated brain trauma increases concern, but they are not interchangeable.

How Is CTE Diagnosed?

Right now, CTE can only be definitively diagnosed after death through a specialized examination of brain tissue. This is one of the most important facts to keep straight, because it affects everythingfrom research to media stories to how clinicians talk with patients.

So what happens during life if someone has symptoms?

Clinicians can evaluate symptoms and risk history and may diagnose treatable conditions (like depression, anxiety, sleep apnea, migraine, or substance use issues) that can mimic or worsen cognitive and mood symptoms. Researchers have also proposed criteria for a clinical syndrome associated with repetitive head impacts, often called traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES). TES is used mainly in research settings to describe patterns of symptoms and exposure history; it is not the same thing as a confirmed CTE diagnosis.

Are there tests for CTE in living people?

Not definitive onesyet. Researchers are investigating tools like advanced brain imaging, blood-based biomarkers, and other measures, but these are still developing. If you see a headline claiming a simple “CTE blood test,” read carefully: it may refer to early-stage research, not something widely validated for routine diagnosis.

What Science Knows (and What It Doesn’t)

Here’s the most honest, useful way to think about the current state of evidence.

What’s reasonably supported

- Long-term exposure to repeated head impacts is associated with increased risk of CTE.

- CTE has a distinctive pattern in the brain involving abnormal tau deposits.

- Symptoms reported in people later found to have CTE can involve cognition, mood, behavior, and movement.

- CTE can’t be confirmed during life with current standard tools.

What’s still uncertain

- Why some people develop CTE and others don’t, even with similar exposure

- How much exposure is “too much” (there’s no universal threshold)

- The role of genetics, age at first exposure, and other health factors

- Exactly how symptoms map to brain changes in an individual person

One important public health message: major health organizations have noted that there isn’t strong evidence that a few concussions or occasional hits automatically lead to CTE. The greatest concern is cumulative exposure over time.

Treatment: What Can Be Done?

There is currently no cure that reverses CTE. Care focuses on:

- Managing symptoms (for example, treating depression, anxiety, sleep problems, headaches, or irritability)

- Supporting cognitive function through structured routines, therapy, and, when appropriate, medications

- Addressing overall brain health (exercise, sleep, nutrition, social support, and controlling cardiovascular risks)

Because CTE shares symptoms with many treatable conditions, getting a thorough medical evaluation matters. Sometimes the best “CTE care” starts with discovering something else that can be improvedlike sleep quality, stress load, untreated ADHD, or chronic migraines.

Prevention and Risk Reduction: The Practical Stuff That Actually Helps

If CTE is strongly linked to repeated head impacts, then risk reduction is mostly about one theme: reduce the number and intensity of head impacts over time. That’s it. That’s the plot.

In sports

- Limit full-contact practices when possible.

- Teach safer techniques (for example, avoiding head-first contact).

- Follow concussion protocols and don’t rush return-to-play.

- Consider lower-impact alternatives (like flag versions of contact sports) when appropriate.

- Use well-fitted protective gearbut don’t treat it like a magical force field.

Protective equipment can reduce certain injuries, but it can’t eliminate brain movement inside the skull. So the biggest wins often come from rules, coaching, and cultureespecially moving away from the “shake it off” mindset.

Outside sports

- Prevent falls (good lighting, safe footwear, physical therapy when balance is an issue).

- Use seatbelts and follow traffic safety guidance.

- Address risk factors early (vision problems, medication side effects, untreated dizziness).

When to See a Doctor

If you (or someone you care about) have a history of repeated head impacts and notice persistent changes in memory, mood, behavior, sleep, or daily functioning, it’s worth talking with a healthcare professional. Ask for a thorough evaluation that considers:

- Medical and mental health history

- Sleep, stress, and substance use

- Neurologic exam and cognitive screening when appropriate

- Other conditions that can mimic or worsen symptoms

Important safety note: If someone is experiencing severe depression or thoughts of self-harm, treat it as an urgent health issue and seek immediate help from a trusted adult, a healthcare professional, or local emergency services.

Big Picture: A Calm Take in a Loud Internet

CTE is real. Repeated head impacts are a real concern. But the loudest voices online often turn complex science into simple storylines: “Concussions equal CTE” or “Helmets fix everything” or “If you played football, you’re doomed.” None of those are accurate.

A more useful framework is this: your brain is worth protecting. Whether you’re a weekend athlete, a former player, a coach, a parent, or someone who just wants to keep their neurons for the long haul, the smartest approach is evidence-based cautionreducing unnecessary head impacts, taking symptoms seriously, and getting proper care rather than guessing.

Experiences Related to CTE: What People Commonly Describe

Because CTE can’t be confirmed during life with a simple test, the “experience” side of this topic often revolves around uncertaintypeople noticing changes and wondering what they mean. Many individuals with a history of repeated head impacts describe a similar emotional pattern: they’re not only dealing with symptoms, they’re dealing with the question mark.

Living with the question mark

For some former athletes, the experience starts with something small: misplacing items more often, struggling to focus at work, or feeling unusually short-tempered. Maybe it’s a spouse noticing that arguments escalate faster than they used to, or a friend saying, “You seem different lately.” The hard part is that these changes can come from dozens of causesstress, poor sleep, depression, anxiety, chronic pain, aging, or past injuries. But once CTE enters someone’s mind, it can become the only explanation that feels big enough to match the fear.

Clinicians who work with people worried about CTE often describe a key turning point: shifting from “Do I have CTE?” to “What’s happening with my health right nowand what can we improve?” That shift matters because many problems that look like “brain decline” respond to real treatment. Sleep disorders, untreated mood disorders, migraines, and even vitamin deficiencies can seriously affect thinking and emotions. Addressing them doesn’t “prove it isn’t CTE,” but it can change daily life in a meaningful way.

The family perspective

Families often describe the experience less in medical terms and more in day-to-day moments: someone becoming more impulsive with money, losing patience with kids, or withdrawing from social life. Care partners may feel like they’re walking on eggshells, especially if irritability or emotional outbursts increase. In these situations, therapy and structured support can help, even when the exact diagnosis remains unclear. A practical strategy many families find helpful is focusing on patterns and triggerssleep deprivation, alcohol, high stress, overstimulationbecause changing those variables can reduce symptom intensity.

Identity, grief, and the “sports shaped me” effect

Another common thread is identity. For lifelong athletes, sports aren’t just an activity; they’re a community, a routine, and a self-image. When brain health concerns show up, it can feel like the cost of something they loved. Some people experience a form of griefsometimes mixed with angerbecause they feel they weren’t fully informed about risks or that the culture rewarded playing through injury. Others feel conflicted, because sports also gave them structure, mentorship, and joy. Both realities can be true at once, and working through that complexity is part of the lived experience.

Coaches and parents: the “I’m trying to do the right thing” dilemma

Coaches and parents often describe a different kind of stress: balancing safety with opportunity. They want kids to be active and build confidence, but they also want to minimize harm. Many describe feeling caught between two extremespanic or denialwhen a calmer middle path is usually best. That middle path looks like: teaching proper technique, choosing leagues that limit unnecessary contact, taking concussion symptoms seriously, and building a team culture where “reporting symptoms” is treated like “good decision-making,” not weakness.

What helps, even without certainty

People who cope best with CTE-related worries often share a similar playbook:

- Get evaluated for treatable causes of symptoms (sleep, mood, headaches, stress).

- Track patterns (what makes symptoms better or worse).

- Prioritize brain basics (sleep, movement, social connection, cardiovascular health).

- Use support (therapy, support groups, cognitive rehab when appropriate).

- Reduce future head impacts (even in recreational sports or daily activities).

In other words: the experience isn’t just fear and headlines. For many people, it becomes a long-term project of protecting brain health, rebuilding routines, and making choices that keep life stable and meaningfuleven when the internet wants everything to be a dramatic plot twist.

Conclusion

CTE is a progressive brain disease associated with repeated head impacts over time. It’s best understood as a long-term risk tied to cumulative exposurenot as a guaranteed outcome from a single concussion. While researchers continue working toward better diagnosis tools for living people, the most useful steps right now are practical: reduce unnecessary head impacts, follow concussion safety protocols, take persistent symptoms seriously, and get a thorough medical evaluation for treatable conditions. The goal isn’t panic. It’s smarter protection for the brain you plan to use for the rest of your life.