Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The simplest shared DNA: both are priced off future cash flows

- The “equity coupon” idea: stocks can behave like bonds in disguise

- Inflation: why it can “swindle” stock investors too

- Rising rates vs rising inflation: same headline, different story

- Equity duration: why some stocks act like long-term bonds

- Stocks vs bonds as competitors: the “relative value” tug-of-war

- Earnings yield, bond yield, and the equity risk premium (without the nonsense)

- Portfolio reality: stocks can diversify bonds (and bonds can diversify stocks)… until they don’t

- Practical examples: seeing the stock-bond resemblance in the wild

- Bottom line: the bond mindset can make you a calmer stock investor

- Experiences Investors Commonly Have With This “Stocks Are Like Bonds” Reality (Extra )

If you’ve ever said, “Stocks are risky, bonds are safe,” congratulationsyou have successfully repeated the

first sentence of every investing 101 slideshow ever made. But here’s the twist: stocks and bonds are

cousins, not strangers. They’re both just different ways of buying a stream of future cash flows, and they

both get moody when inflation and interest rates start doing the cha-cha.

The fun part is that once you start viewing stocks through a “bond lens,” a bunch of confusing market behavior

suddenly makes sense: why “growth stocks” can act like long-term bonds, why inflation can hurt equities even

though companies sell “real stuff,” and why sometimes stocks help diversify bonds (yes, really).

The simplest shared DNA: both are priced off future cash flows

Strip away the tickers, jargon, and dramatic headlines, and you’re left with a basic reality: both stocks and

bonds are valued by discounting expected future cash flows back to today.

Bonds: the cash flows are promised

A traditional bond is the cleanest version of this idea. You know the coupon payments, you know the maturity

date, and you can estimate the yield. The big question is whether the issuer pays you back and how market

interest rates move while you’re holding the bond. When yields rise, existing bond prices usually fall. When

yields fall, existing bond prices tend to rise. It’s math, not magic.

Stocks: the cash flows are “messier,” but the math idea is the same

With stocks, you don’t get a contract that says, “Here is your coupon, enjoy.” Instead, you own a claim on a

company’s future profits and distributionsdividends today, buybacks tomorrow, reinvestment that (hopefully)

becomes bigger profits later. The exact cash flows are uncertain, but the valuation logic is still: future

cash, discounted to the present, minus the market’s daily emotional weather.

In other words, stocks aren’t “random.” They’re just bonds with variable coupons and no maturity date. Which

sounds terrifying until you remember that bonds can be terrifying too (hello, 2022).

The “equity coupon” idea: stocks can behave like bonds in disguise

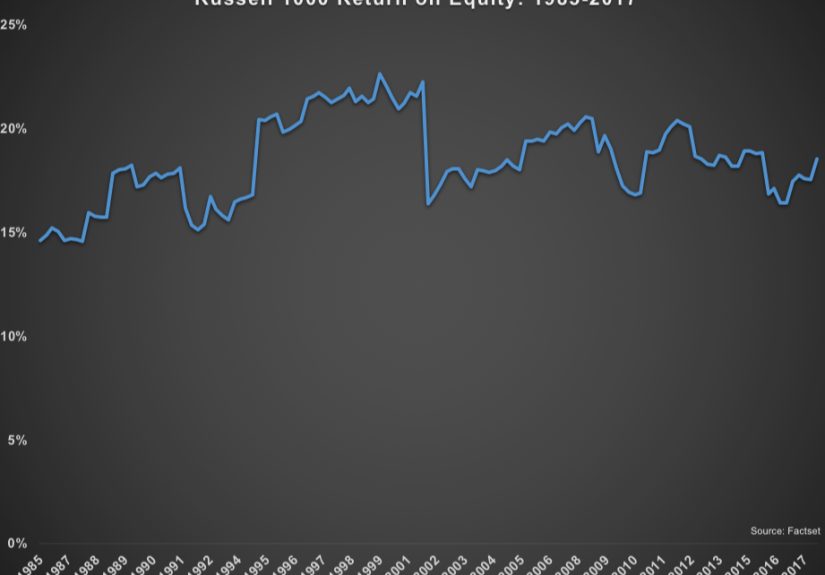

A classic argument (popularized in modern investing conversations) is that corporate profitability tends to be

more stable over long stretches than people assume. Even though individual companies swing wildly, the broad

market’s return on equity (ROE) has often been relatively steady compared with the day-to-day drama of stock

prices.

Think of ROE as the market’s “earnings engine” relative to the shareholder capital behind it. If that engine

doesn’t wildly change from decade to decade, you can squint and see something that looks bond-ish: a

semi-stable earning power that functions like an “equity coupon.” The stock market price, however, behaves

like the bond pricerising and falling as investors change the discount rate they demand.

This framing helps explain a weird truth: stocks can get hit not only when profits weaken, but also when the

“price of money” changes. If investors suddenly demand a higher return (because yields rose, risk appetite

changed, or inflation got spicy), stock valuations can compress even if the company is still making money.

Inflation: why it can “swindle” stock investors too

Bonds are the obvious inflation victim. If your bond pays a fixed coupon and inflation rises, your purchasing

power shrinks. You’re earning dollars that buy fewer groceries, fewer plane tickets, and fewer streaming

subscriptions you forgot to cancel.

Stocks feel like they should be immune because companies can raise prices. Sometimes they can. But inflation

can still hurt equities through multiple channels:

1) Higher discount rates can shrink valuations

Inflation often pushes interest rates higher (or at least pushes expectations higher). Higher rates tend to

raise the discount rate investors apply to future cash flows. When the discount rate rises, the present value

of far-off cash flows falls. This is the same basic mechanism as bond price declines when yields rise.

2) Costs rise too (and margins are not invincible)

Companies don’t just sell things; they buy thingslabor, materials, energy, shipping, components, and the

occasional executive-level coffee habit. If costs rise faster than prices, profit margins get squeezed. Even

if revenue climbs, earnings growth can lag.

3) Inflation can increase the amount of capital a business must reinvest

In higher inflation environments, working capital needs often grow. Inventory costs more, replacing equipment

costs more, and maintaining the same real business capacity can require more dollars. That can reduce the

cash available to distribute to shareholdersagain, bond-like logic: your “coupon” might not stretch as far as

you hoped.

Put these together and you get a very unromantic conclusion: stocks are not an automatic inflation shield.

They can be a partial shield if companies have strong pricing power and inflation stays moderate. But when

inflation jumps and stays hot, both stocks and bonds can suffer at the same time.

Rising rates vs rising inflation: same headline, different story

Investors often lump “rates are going up” into one bucket. But markets care about the why.

When rates rise because growth is strong

If interest rates rise because the economy is strengthening, companies may also be growing sales and profits.

In that case, rising rates can coexist with decent stock returns. Bonds may still take a hit from higher

yields, but equities can sometimes shrug and keep movingespecially if earnings momentum is strong.

When rates rise because inflation is running hot

If rates rise because inflation is accelerating, the environment can be more hostile for both asset classes.

Stocks face valuation pressure and margin pressure. Bonds face price declines and the ongoing “your coupon is

being eaten alive” problem. This is one reason inflation is often the culprit when both stocks and bonds have

a rough year together.

Same rate direction. Totally different vibe.

Equity duration: why some stocks act like long-term bonds

Duration is a bond concept that measures sensitivity to interest-rate changes. Long-duration bonds (think

long maturities) typically move more when rates change. Short-duration bonds move less.

Stocks have something similaroften called “equity duration.” The idea is straightforward: the more of a

stock’s value is tied to cash flows far in the future, the more sensitive that stock tends to be when

discount rates change.

“Long-duration” stocks: growth and high-multiple names

Companies expected to generate a big portion of their cash flows far down the road often trade at higher

valuation multiples today. If rates rise, those distant cash flows get discounted more heavily, and prices

can drop sharply. This is why some growth-heavy segments can feel like “bond proxies” during rate shocks.

“Short-duration” stocks: value, dividends, and near-term cash generation

Companies that return more cash todaythrough dividends or buybacksoften behave more like shorter-duration

assets. They can still fall in a bear market, of course, but their valuations may be less dependent on

ultra-low discount rates.

This doesn’t mean “growth bad, value good.” It means interest-rate sensitivity isn’t evenly distributed

across the stock market. Rate changes don’t hit every ticker the same wayjust like they don’t hit every bond

the same way.

Stocks vs bonds as competitors: the “relative value” tug-of-war

Your money is always choosing between options: stocks, bonds, cash, real estate, and whatever your cousin is

pitching at dinner (“It’s like Bitcoin but with more synergy!”).

When bond yields are low, stocks often look comparatively attractive because the “alternative” is earning

very little in fixed income. When bond yields rise, bonds become more competitive. Suddenly, investors can

get meaningful income without needing a company to grow earnings, expand margins, and cure a disease.

This is where the stock-bond similarity becomes practical: both assets are priced off required returns. If

bonds start offering higher returns with lower risk, investors may demand a higher expected return from

stocks too. One way the market can deliver that higher expected return is by lowering stock prices today

(so future returns, mathematically, improve).

Earnings yield, bond yield, and the equity risk premium (without the nonsense)

A popular way to compare stocks and bonds is to look at the stock market’s earnings yield (roughly the inverse

of the P/E ratio) versus Treasury yields. The difference is often framed as an “equity risk premium” concept:

how much extra return you expect from stocks compared with bonds.

Helpful, but not a crystal ball

Comparing yields can be useful because it forces you to think in “cash flow terms.” But it can also be abused

with simplistic takes like “stocks are cheap because earnings yield is higher than bond yield,” ignoring

inflation, growth expectations, profit margins, and risk.

Make it more real: think in scenarios

Instead of treating yield comparisons like a fortune cookie, try scenario thinking:

- What if inflation stays elevated and real rates remain higher?

- What if earnings growth slows because margins compress?

- What if productivity improves and growth holds up even with higher rates?

In each case, stocks can still be “bond-like” in the sense that a changing discount rate can dominate price

moves, even when the business outlook hasn’t changed much.

Portfolio reality: stocks can diversify bonds (and bonds can diversify stocks)… until they don’t

Many investors learned a simple rule: “When stocks fall, bonds rise.” Historically, that pattern has shown up

often because in economic slowdowns investors flee to safety, and central banks may cut ratesboosting bond

prices.

But the relationship is not a law of physics. In inflation shocks, both can fall together. When inflation

forces rates higher, bonds drop from rising yields, and stocks can drop from both valuation compression and

profit pressure.

The takeaway isn’t “bonds are useless” or “stocks are doomed.” It’s that diversification depends on the type

of shock. Growth shocks and deflationary scares often favor bonds. Inflation shocks can punish both.

So what do you do with this information?

-

Diversify across different “durations.” In bonds, that means mixing maturities. In stocks,

it means not accidentally loading up on only long-duration equity exposure. -

Favor quality and pricing power. Companies that can raise prices without losing customers

tend to handle inflation better than those competing only on price. -

Stay humble about the macro. Predicting inflation and rates consistently is hard. Build a

portfolio that doesn’t require you to be a wizard.

And yes, none of this is personalized financial advice. It’s portfolio common sense with a side of “markets

are complicated, please don’t mortgage your house to buy a narrative.”

Practical examples: seeing the stock-bond resemblance in the wild

Example 1: When “safe growth” stopped feeling safe

In periods of ultra-low rates, long-duration stocks (often high-multiple growth companies) can soar because

the discount rate is low and investors are willing to pay up for future potential. But when rates rise,

those same stocks can reprice fastsimilar to what happens to long-term bonds when yields jump.

Example 2: When both stocks and bonds fell together

Inflation-driven rate hikes can create a tough environment where bonds lose value as yields rise and stocks

also drop as valuations compress. Investors expecting bonds to “save the day” may be surprised when the usual

negative correlation weakens or flips.

Example 3: When dividends and buybacks look like a “floating coupon”

Mature companies that consistently return cash to shareholders can be easier to think about in bond terms:

you’re receiving ongoing distributions that may grow over time. It’s not fixed like a bond coupon, but the

investor experience can feel similarespecially if you focus on income and long holding periods.

Bottom line: the bond mindset can make you a calmer stock investor

If you only think of stocks as “random price lines,” you’ll be at the mercy of headlines. If you think of

stocks as claims on cash flowspriced with a discount rate, sensitive to inflation, and influenced by

competing yieldsyou start to understand why markets move the way they do.

Stocks aren’t bonds. They’re riskier, more volatile, and way more dramatic on social media. But they share

the same valuation foundation. And once you get that, you can stop being shocked when stocks behave like a

long-term asset whose price depends on the level and direction of ratesbecause that’s exactly what they are.

Experiences Investors Commonly Have With This “Stocks Are Like Bonds” Reality (Extra )

The most memorable “stocks are more like bonds than you think” moment usually isn’t learned from a textbook.

It’s learned the hard wayright around the time someone in your group chat says, “Wait… why is my stock fund

down when the company’s earnings look fine?”

One common experience happens when investors fall in love with a story stock and accidentally buy duration.

They don’t think they’re buying duration, of course. They think they’re buying “innovation,” “the future,”

and a CEO who wears the same hoodie every day to prove they’re too busy changing the world to pick outfits.

Then rates rise. Suddenly, the market doesn’t want to pay 40 times earnings for cash flows that might show up

in the distant future. The company may still be growingcustomers still exist, products still shipbut the

valuation multiple shrinks. It feels unfair until you realize it’s basically the equity version of a long-term

bond getting punched when yields climb.

Another experience: the “diversification betrayal.” Many investors build a classic stock-and-bond portfolio

expecting bonds to be the emotional support animal when stocks panic. Then an inflation shock arrives and

bonds don’t provide comfortthey join the tantrum. If you lived through a period where both fell together,

you probably remember the confusion: “I thought bonds were supposed to be safe.” The lesson isn’t that bonds

are broken; it’s that bonds are sensitive to inflation and rate moves, and stocks can be sensitive to the

same forces. When the discount rate regime changes, the whole portfolio notices.

A third experience is more encouraging: the “I got paid to wait” realization. Investors who focus on cash

distributionsdividends and buybacksoften find it easier to stay calm during price swings. When the market

drops, they still see money being returned to shareholders, and they treat it like a growing coupon rather

than a promise of instant price appreciation. Over time, that mindset can reduce the urge to panic-sell at

the worst moment. It’s not a guarantee of success, but it’s a psychological advantage: you’re anchoring on

cash flow, not mood.

Finally, there’s the experience of learning that “rates” are not just a bond investor’s problem. Many people

first pay attention to interest rates when they refinance a mortgage. But markets are full of invisible

refinancing: every day, stocks are effectively “re-priced” based on what return investors demand. When that

demanded return changesbecause of inflation fears, policy shifts, or risk appetitestocks can revalue quickly,

just like bonds do. Once you’ve seen it happen a few times, you stop asking, “Why did stocks drop today?”

and start asking the more useful question: “Did expected cash flows change, or did the discount rate change?”

That’s the practical payoff of the bond lens. It won’t eliminate volatility, but it can turn market chaos

into something more understandableand understanding is underrated in a world where a single tweet can

temporarily move billions of dollars.