Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Market Cycles” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- Why Going “Way Way Back” Helps Your 2026 Brain

- A Decade-by-Decade Reality Check

- The Long-Run Scoreboard: Stocks, Bonds, Cash, and Housing

- The Emotional Cycle: Markets Move, People React

- The “Don’t Miss the Bounce” Problem

- How to Build a Plan That Survives Cycles

- Common Cycle Traps (and How to Sidestep Them)

- Conclusion: The Best Cycle Is the One You Don’t Quit

- Experiences Related to the Topic: Living Through Market Cycles (Extra 500+ Words)

Market cycles have a talent for making smart people act like they’ve never met a chart before.

One decade, stocks are the hero. The next, bonds quietly win the award for “Most Likely to Keep You Sane.”

And every cycleno matter how familiarshows up in a different costume so it feels brand-new.

In Ben Carlson’s classic A Wealth of Common Sense post, the big idea is simple: zoom out until your daily market anxiety

becomes the size of a grain of sand. Not because the past predicts the future (it doesn’t), but because it helps you

prepare for the kinds of environments markets regularly throw at investors: booms, busts, inflation spikes,

falling rates, rising rates, “lost decades,” and sudden recoveries that happen while everyone is still doomscrolling.

What “Market Cycles” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

A market cycle is the recurring pattern of expansion and contraction in prices, sentiment, and risk-taking.

It’s related to the economy, but it isn’t the same thing. The economy has business cycles (growth, slowdown, recession, recovery),

and the stock market tends to move ahead of those shiftsoften changing direction before the headlines do.

The most useful definition is practical: market cycles are the reason your portfolio can look like a genius one year

and a clown car the nextwithout you changing a thing.

Two important clarifications

- A cycle isn’t a schedule. There’s no cosmic calendar where bears punch in for work every 7.3 years.

- A cycle isn’t a prophecy. History is a guidebook, not a fortune cookie.

Think of cycles like seasons. Winter comes back, but it never shows up with the same exact temperature, timing, or snowstorm pattern.

You can’t predict the day it’ll snow. You can decide to own a coat.

Why Going “Way Way Back” Helps Your 2026 Brain

Most investors live inside a tiny reference point“since last month,” “since my last deposit,” or “since I started investing.”

That’s understandable, but it’s also how cycles mess with your decision-making.

When you zoom out by decades, two truths become obvious:

- Markets are cyclical by nature. Leadership rotates. Conditions change. Easy wins become hard wins.

- Your feelings are cyclical too. Optimism turns into confidence, confidence into euphoria, and euphoria into “wait, why is everything on fire?”

Carlson’s decade-by-decade view is basically a vaccination against recency bias. It won’t make downturns feel good

nothing makes downturns feel goodbut it can stop you from treating every scary moment like it’s the first scary moment in history.

A Decade-by-Decade Reality Check

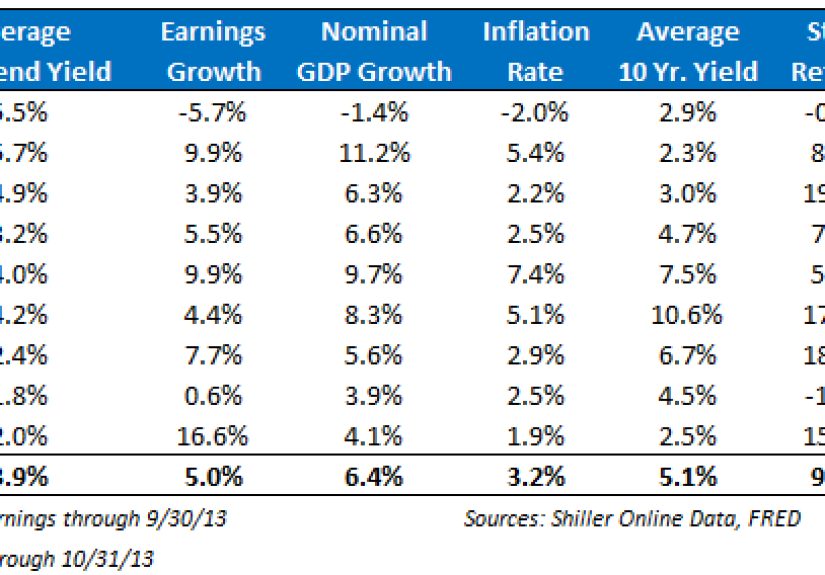

Here’s the big “way way back” takeaway: stock returns are feast-or-famine depending on the decade.

The economy can look relatively stable while markets swing wildly. Inflation can be quiet for yearsthen suddenly become

the main character. Interest rates can rise and stocks can still do fine. And sometimes, bonds actually beat stocks.

Dividends and earnings: the boring math behind the drama

A helpful mental model is that long-run stock returns are driven largely by two engines:

dividend yield (the cash companies pay out) and earnings growth (the cash companies generate).

Prices can swing more than fundamentals in the short run, but over long stretches, fundamentals tend to matter a lot.

That’s why a decade-level lens is so useful: it lets you see when the “engines” were strong, when valuations did the heavy lifting,

and when investors paid the price for optimism getting ahead of reality.

When bonds win (yes, it happens)

There are periods where bonds outshine stocksnot because bonds are exciting (they’re not),

but because stocks can go through long stretches of disappointment. If your entire plan assumes stocks always beat bonds

over every meaningful timeframe, you’re going to have a rough emotional ride precisely when discipline matters most.

Inflation: the quiet villain of “real” returns

Inflation doesn’t need to crash your portfolio to hurt you. It can simply erode purchasing power slowly, like a leaking tire.

During high-inflation regimes, investors often discover the difference between “my account balance went up” and

“my money buys more stuff.” Those are not the same thing.

In decade terms, there have been stretches where stocks didn’t keep up with inflation, and stretches where bonds delivered

weak real returns even if nominal returns were positive. That’s why diversification isn’t about maximizing fun;

it’s about maximizing your odds of sticking with a plan.

The Long-Run Scoreboard: Stocks, Bonds, Cash, and Housing

One of the most grounding exercises is looking at long-run returns across major asset classes. In Carlson’s post,

the “really long-term” numbers (1928–2013) show stocks leading, with bonds and cash trailing, and housing providing

more modest growthespecially after adjusting for inflation.

The lesson isn’t “stocks always win.” The lesson is: time and compounding are powerful,

but only if you can stay invested through the messy middle parts (which is… most parts).

What this view is actually good for

- Setting expectations: markets reward patience, not perfection.

- Building humility: no single decade should become your “forever forecast.”

- Planning behavior: the biggest threat isn’t volatilityit’s panic.

If you want the shortest possible summary: the long run tends to reward risk-taking, but the short run tests whether

you deserve the long run.

The Emotional Cycle: Markets Move, People React

Market cycles aren’t just about returns. They’re about investor behavior.

When prices rise, narratives get more confident. When prices fall, narratives get more certain in the other direction.

The cycle of emotions often looks like: hope → optimism → confidence → thrill → euphoria → anxiety → denial → fear → capitulation → despair → disbelief → relief.

This emotional loop matters because it can turn a decent plan into a self-sabotage machine:

buy high when confidence is loud, sell low when fear is louder, then wait for “clarity” that only arrives after prices recover.

The behavior gap is real (and expensive)

Studies of investor behavior frequently show that the average investor’s realized returns can lag the returns of the investments

they ownlargely due to mistimed buying and selling. In plain English: people often underperform their own portfolios

because they can’t stop touching the stove.

Cycles are why “knowing where you are” beats “predicting what’s next”

One of the best cycle mindsets comes from investors who obsess less about forecasts and more about positioning.

You may not know what next year will bring, but you can usually tell whether markets feel cold and fearful or hot and frothy.

That doesn’t mean you time tradesit means you manage risk, expectations, and behavior.

The “Don’t Miss the Bounce” Problem

A cruel feature of market cycles is that the best days often cluster near the worst days.

Big movesdown and uptend to happen during volatile periods. That’s exactly when people are most tempted to exit.

The result is the classic tragedy: investors sell to “avoid more pain,” then miss the rebound that does most of the repair work.

It’s like leaving the gym after the warm-up and still expecting abs.

Why market timing is harder than it looks

- You have to be right twice: when to get out and when to get back in.

- News is a lagging indicator: by the time it feels “safe,” prices may have already moved.

- Volatility is deceptive: it feels like chaos, but it’s also where recoveries are born.

Many “stay invested” studies show the same theme: missing a small number of strong market days can meaningfully reduce long-term returns.

That’s not because markets are magicit’s because compounding is picky about consistency.

How to Build a Plan That Survives Cycles

If market cycles are inevitable, your strategy should assume they’ll show uplike taxes, traffic, and someone replying “per my last email.”

The goal isn’t to eliminate volatility. The goal is to design a system you’ll actually follow.

1) Choose an asset allocation you can live with

Asset allocation is your “volatility thermostat.” Stocks may drive growth, bonds may reduce the gut-punch factor,

and cash can be a short-term stability tool (not a permanent lifestyle choice).

Simple frameworkslike a mostly-stock portfolio plus a bond buffercan work well for many long-term investors.

The best allocation is the one you’ll stick with when markets are doing their scariest impression of a roller coaster.

2) Automate contributions (especially when it feels wrong)

Regular investinglike dollar-cost averagingcan turn volatility into a feature instead of a bug. When prices are down,

your contributions buy more shares. When prices recover, those shares participate in the rebound.

3) Rebalance with rules, not vibes

Rebalancing is the adult version of “take profits and buy what’s on sale,” without pretending you can predict next month.

If stocks run up and dominate your portfolio, rebalancing trims risk. If stocks crash and shrink, rebalancing nudges you to buy

when it feels emotionally unpleasantoften the exact time discipline is most valuable.

4) Use history as perspective, not a prediction engine

Historical averages can be helpful, but only if you treat them as a rangenot a promise. Valuations, inflation regimes,

policy environments, and investor behavior all change. A wise approach is to let history inform your expectations

without letting it dictate your certainty.

5) Keep your “cycle-proof” habits boring

- Maintain diversification.

- Keep costs and taxes as low as reasonably possible.

- Have a written plan for what you’ll do in a bear market (before the bear shows up).

- Limit portfolio-checking when volatility spikes (yes, that’s allowed).

Common Cycle Traps (and How to Sidestep Them)

Trap: “This indicator worked last time, so it will work forever.”

Indicators can provide context, but no single metric is a universal remote control for markets. If your entire strategy depends on one signal,

you’re not investingyou’re auditioning for stress.

Trap: “Cash is safe, so I’ll wait until it feels safe to buy.”

Cash can reduce volatility, but it can also create a different risk: missing compounding and losing purchasing power to inflation over time.

Waiting for comfort often means buying after prices have already recovered.

Trap: “The last decade’s winner is the only thing that matters.”

Decade leadership rotates. What worked great recently can underperform next. Diversification is the antidote to falling in love with the past.

Trap: “If I feel anxious, I should take action.”

Anxiety is not a signal; it’s a sensation. Your plan should tell you when to actideally based on goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance,

not your nervous system.

Conclusion: The Best Cycle Is the One You Don’t Quit

The whole point of going “way way back” is not to worship history. It’s to build resilience.

When you understand that markets have survived decades of wildly different conditionsbooms, busts, inflation spikes,

rate shocks, bubbles, crashesyou stop expecting a smooth ride and start building a plan that assumes turbulence.

Market cycles will keep cycling. Your job is to keep showing upconsistently, patiently, and with a strategy that doesn’t require you

to be a forecasting wizard. Because the market doesn’t reward the most emotional person in the room.

It rewards the person who can stay invested while everyone else auditions for a panic-selling documentary.

Experiences Related to the Topic: Living Through Market Cycles (Extra 500+ Words)

If you want to understand market cycles, don’t start with spreadsheetsstart with the human experience of living through one.

Because the real challenge isn’t knowing that cycles exist. The real challenge is what a cycle does to your brain at 2:00 a.m.

when your portfolio feels like it’s being graded by a moody professor.

Experience #1: The “I Started Investing at the Worst Time” phase

Many investors describe a painfully common origin story: they finally start investing, and almost immediately the market drops.

It feels personal, like the market waited for them to click “Buy” before pulling the rug. In cycle terms, this is normal.

Your start date is just a random dot on a very long timeline.

The investors who make it through this phase usually do two things: (1) they keep contributing on schedule, and (2) they stop treating

a short-term dip as proof they were “wrong.” Over time, those early contributions during ugly periods often become the ones that look smartest,

because they were bought at lower prices. It’s not fun in the moment. It’s just effective later.

Experience #2: The “Everything is different now” storyline

Another common experience is narrative overload. During a boom, the story is that a new era has arrived and old rules don’t apply.

During a bust, the story is that the system is broken and recovery is impossible. In both cases, the storyline can feel airtight because

it’s supported by real eventsnew technology, new policy, new risks, real pain.

What cycle-aware investors learn is that “different” doesn’t mean “never happened before in any form.”

Every cycle has unique catalysts, but human behavior tends to rhyme. Excitement leads to overreach. Overreach leads to disappointment.

Disappointment creates opportunityusually when people feel least interested in taking it.

Experience #3: The “I sold to feel better… and it worked (briefly)” trap

Selling during a downturn can feel like relief. You stop watching the red numbers. You sleep better for a week.

And then the market bounces, and you’re stuck with a new problem: deciding when to re-enter.

That decision is harder than the exit, because it requires buying when the headlines still look scary.

Investors who have been through this once often describe a lasting lesson: the pain of volatility is temporary,

but the pain of missing a recovery can linger. Many end up creating a personal rulelike rebalancing bands,

automatic contributions, or a written “bear market checklist”because they don’t want their future self making

high-stakes decisions while emotionally compromised.

Experience #4: The “I finally learned what risk tolerance actually means” moment

Risk tolerance isn’t what you put on a questionnaire when markets are calm. It’s what you can live with when markets are not.

Many investors only discover their true tolerance after they experience a real drawdown. The healthiest outcome isn’t shame.

It’s adjustment: a more realistic allocation, a bigger cash buffer for near-term needs, or a shift toward a plan that reduces

the temptation to panic.

In other words, market cycles are not just price cycles. They’re education cycles. They teach you what you value:

growth, stability, flexibility, or peace of mind. And once you design a portfolio that matches your life (not your ego),

cycles don’t disappearbut they become survivable. Even manageable.

That’s the “way way back” wisdom in real life: you don’t need to predict the next cycle. You need a plan that can live through it.