Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- ASL Isn’t “English on the Hands”So Why Start With the Alphabet?

- Meet VulcanV3: A Low-Cost, Open-Source Ambidextrous Fingerspelling Hand

- The Control Stack: How a Robot Hand “Says” Letters

- Accuracy: Can Humans Actually Read the Robot’s Fingerspelling?

- What This Robot Hand Canand Can’tDo for Accessibility

- Why Ambidexterity Matters More Than It Sounds

- Design Lessons: What VulcanV3 Gets Right (Even If You Never Build One)

- What’s Next: From Alphabet to Real Interaction

- Conclusion: A Small Hand, A Big Signal

- Experience Add-On (Approx. ): What It’s Like Around a Signing Robot Hand

If you’ve ever watched someone fingerspell in American Sign Language (ASL), you know it’s equal parts language and choreography.

Now imagine a robotic hand doing itsmoothly, consistently, and (here’s the flex) in either a left-hand or right-hand configuration.

That’s not just a party trick for engineers. It’s a tiny glimpse of what “accessible tech” looks like when it’s built with creativity,

affordability, and a healthy disrespect for the idea that robotics must be expensive to be impressive.

This article dives into an open-source, 3D-printed ambidextrous robotic hand that can fingerspell the entire ASL alphabet.

We’ll unpack what “ambidextrous” really means in a one-handed robot, why fingerspelling matters, how the mechanics work,

and where projects like this can go nextwithout pretending a single hand can replace interpreters, Deaf culture, or the full richness of ASL.

(A robot hand can do letters; it can’t do the eyebrow grammar. Yet.)

ASL Isn’t “English on the Hands”So Why Start With the Alphabet?

First, a reality check: ASL is a complete natural language with its own grammar, expressed through hand and body movement,

facial expression, and spatial structure. It is not a manual version of English. That matters, because when technology projects

treat sign language like a simple “hand gesture dictionary,” they miss the pointand often miss the community.

So why would a robotic hand focus on fingerspelling (the manual alphabet) instead of full sign language?

Because fingerspelling is a practical starting point: it’s finite (26 letters), measurable (did the handshape match?),

and widely used for names, places, acronyms, and words without a standard sign. It’s also a gateway skill for learners.

In short, fingerspelling is where language, literacy, and engineering can shake handspun fully intended.

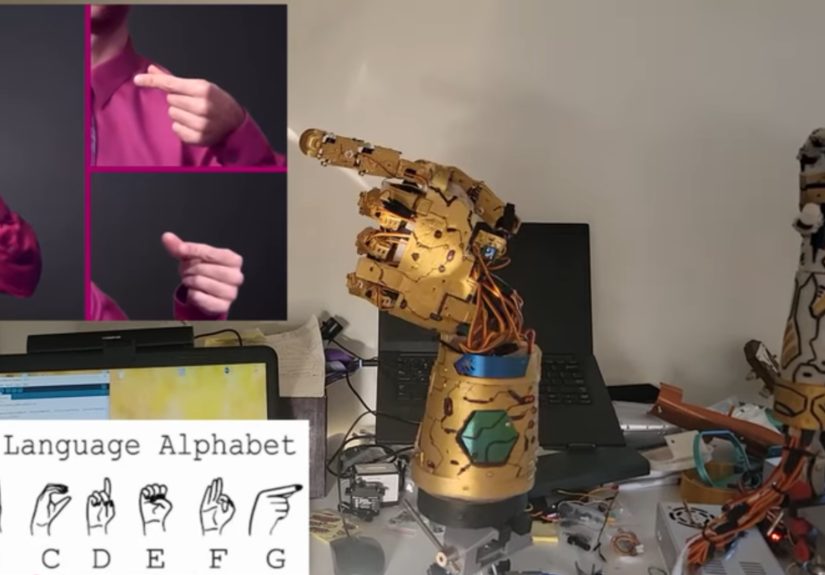

Meet VulcanV3: A Low-Cost, Open-Source Ambidextrous Fingerspelling Hand

The project that put this idea on the map is VulcanV3, a low-cost, open-source, 3D-printed ambidextrous robotic hand

built to reproduce the full ASL alphabet in both right-hand and left-hand configurations. The creator’s approach is refreshingly direct:

if human hands can do it with bones, tendons, and years of practice, a robot can do it with plastic, servos, and unapologetically specific angles.

Ambidextrous, But Make It Mechanical

In humans, ambidexterity is a brain-and-muscle story. In robotics, it’s a geometry story.

VulcanV3 is designed so it can be configured to fingerspell as either a right hand or a left handeffectively “mirroring” the alphabet.

That’s not only clever; it’s useful. Left-handed signing is a real thing, and building a system that can demonstrate both configurations

makes the tool more flexible for education, demos, and experimentation.

Direct-Drive Servos: The “More Motors, Fewer Mysteries” Strategy

Many robotic hands use tendons, cables, springs, or remote actuation to keep the hand light and reduce the number of motors.

VulcanV3 goes the other way: it uses 23 direct-drive servo actuators to articulate fingers and wrist/forearm joints.

The tradeoff is obviousmore servos means more wiring, more calibration, and more opportunities to learn new curse words.

The upside is also obviousdirect control can simplify mapping finger positions to ASL handshapes with repeatable, programmable precision.

In practical terms, direct-drive makes it easier to say, “Letter ‘R’ equals these joint angles,” and have the hand do that consistently,

without the variability introduced by stretchy tendons or cable friction. It’s brute force, but it’s an organized kind of brute force.

What It’s Made Of (And Why It Looks Like It Belongs in a Museum Exhibit)

VulcanV3 is primarily 3D-printed, using materials like PLA for fingers and nylon for more structural parts such as the palm/forearm.

The build is intentionally accessible: off-the-shelf electronics, printable parts, and open files. And yessome builds are finished in a gold paint job,

because if your robot hand is going to spell at people, it might as well do it with dramatic flair.

The Control Stack: How a Robot Hand “Says” Letters

Here’s the secret sauce: the robot doesn’t “understand” language. It executes pose programs.

Each letter in the ASL manual alphabet is represented by a specific handshape, which can be approximated by a set of joint angles.

VulcanV3 uses an Arduino Mega paired with PCA9685 PWM driver modules to control the servo fleet.

That combination is popular in DIY robotics for a reason: it’s affordable, well-documented, and doesn’t demand a PhD in suffering.

The hand’s software maps each letter to servo positions for both hand configurations. That means you can run a sequence like:

neutral pose → A → B → C … → Z → neutral pose, then repeat in the mirrored configuration.

It’s the robotic equivalent of practicing scales on a pianoexcept the piano is your wiring harness.

Accuracy: Can Humans Actually Read the Robot’s Fingerspelling?

A fingerspelling robot hand lives or dies by one question: Do people recognize what it’s forming?

VulcanV3’s write-up reports empirical testing that reproduced all ASL alphabet handshapes in both configurations, plus a small participant study

in which viewers identified letters with high recognition accuracy. That’s an encouraging signalnot because it proves the hand is “fluent,”

but because it proves the shapes are legible to humans, which is the entire point of the exercise.

But recognition isn’t magic; it’s design discipline. Fingerspelling can be tricky even between humans because of speed, coarticulation

(letters influencing each other in a flowing word), and viewing angle. A robotic hand has advantages (repeatability) and disadvantages

(stiffness, limited micro-adjustments, and the fact it can’t naturally “cheat” with human softness).

What This Robot Hand Canand Can’tDo for Accessibility

Let’s be careful with the hype. A robotic hand that fingerspells the alphabet is not a replacement for interpreters.

It’s not a universal translator. It’s not “sign language solved.”

What it is can still be valuable:

- Education tool: A consistent, repeatable demo of the manual alphabet for learners who want to practice recognition.

- Maker-friendly assistive prototype: A low-cost platform that researchers and builders can extend into more complex signing behaviors.

- Exhibit or outreach device: Museums, STEM programs, and accessibility showcases can use it to spark conversations about Deaf culture and tech.

- Research stepping stone: Fingerspelling is a contained task that helps test dexterity, control, and legibilityuseful metrics for robotic hands.

The biggest “can’t” is also the most important: ASL communication is more than handshapes.

Meaning lives in motion, space, facial expression, and context. A hand alone is like a keyboard without a screen:

it can generate symbols, but it can’t guarantee understanding.

Why Ambidexterity Matters More Than It Sounds

You might wonder: if the hand can already do the alphabet, why bother with left-hand and right-hand configurations?

Because real communication is messy, and people are diverse. Some signers favor one hand, some mirror based on positioning,

and learners may benefit from seeing both orientations depending on how instruction is delivered (in-person vs. video, mirrored camera views, etc.).

Ambidexterity also forces the engineering to be more thoughtful: mirroring a handshape isn’t always trivial, and a design that supports both

nudges the project toward robustness rather than a one-off demo.

Design Lessons: What VulcanV3 Gets Right (Even If You Never Build One)

1) It’s Open-Source, Which Means It Can Grow Up

Open projects invite iteration: improved joints, quieter servos, better wrist articulation, refined hand proportions, stronger materials,

and alternative control methods. Accessibility tech benefits enormously from this because the “right” solution depends on context and users

and no single team can guess every context.

2) It Prioritizes Legibility Over Flash

A robot hand can do plenty of impressive things that are useless for communication.

Fingerspelling flips the priority: the output has to be readable by a person.

That’s a design constraint with teeth, and it’s the kind of constraint that creates better robotics.

3) It’s Affordable Enough to Be Reproducible

A “breakthrough” that costs thousands of dollars is often just a press release with screws.

A system that targets a few hundred dollars is a platform. It can be used in classrooms, labs with tight budgets,

and by makers who don’t have corporate sponsorship and a spare aerospace machine shop.

What’s Next: From Alphabet to Real Interaction

If you’re thinking, “Coolnow make it sign whole words,” you’re not alone. The next steps typically fall into three lanes:

- More articulation: Better wrist motion, smoother transitions, and more natural hand dynamics for clarity and speed.

- Better language modeling: Turning text into fingerspelled sequences with timing rules, coarticulation modeling, and readability checks.

- Community-centered design: Involving Deaf signers early and often to ensure the output is useful, respectful, and not built on assumptions.

Even without “full signing,” a refined fingerspelling hand could plug into kiosk interfaces, museum placards, classroom tools,

and accessibility demosespecially if paired with captions, visuals, or haptic/tactile feedback experiments for Deaf-blind communication research.

Conclusion: A Small Hand, A Big Signal

VulcanV3 doesn’t claim to replace language. It demonstrates something more grounded and, in some ways, more powerful:

high-dexterity assistive robotics can be open, affordable, and legible.

It also reminds us that “communication tech” isn’t only microphones and speech-to-text.

Sometimes it’s a gold-painted robot hand quietly spelling out lettersinviting engineers to build better tools,

and inviting everyone else to recognize that accessibility is a design choice, not an afterthought.

Experience Add-On (Approx. ): What It’s Like Around a Signing Robot Hand

Even if you never print a single part, projects like an ambidextrous ASL fingerspelling hand tend to create the same set of experiences

wherever they show up: workshops, classrooms, maker spaces, robotics clubs, and accessibility demos. The first experience is almost always

calibration reality. In videos, the hand snaps into crisp poses like it’s following choreography. In real life, your “A” might look

like a crab trying to hold a marble. You learn quickly that one servo horn being a tooth off can turn a confident “M” into an “N,” and suddenly

you’re doing robotics and typography: tiny adjustments, constant checking, and the occasional dramatic sigh.

Then comes the moment builders chase: the first perfectly readable letter. It’s oddly satisfyinglike hearing a musical instrument play

its first clean note. People tend to celebrate the same way, too: they run the alphabet once, then run it again, then film it from three angles

because proof is a powerful motivator. That’s also when you start noticing the “human factors” you didn’t plan for. Servos whine. Lighting changes

how readable a pose looks on camera. A gold finish can make joints pop visually (great for demos) but also reflect glare (not great for legibility).

You begin to understand that communication devices aren’t only about mechanicsthey’re about how humans perceive output in real spaces.

In educational settings, the strongest moments often happen when the hand becomes a conversation starter instead of a “solution.”

Students ask why fingerspelling matters. Someone brings up that ASL isn’t English. Another person asks about interpreters, captioning, and why

accessibility tech needs community input. A good facilitator uses the robot hand the way you’d use a telescope: not to replace the sky,

but to help people see what they’ve been missing. The project becomes a bridge between STEM curiosity and real-world inclusivity.

When Deaf community members are involved (as they should be), the experience typically becomes more honestand more useful.

Feedback tends to be specific: which letters are easily confused, which transitions look unnatural, whether the wrist position helps or hurts,

and how speed affects recognition. People also point out something engineers sometimes overlook: fingerspelling is often dynamic.

Even “static” letters carry subtle motion and timing. That kind of critique is gold (again: pun intended), because it moves the project

from “cool demo” toward “usable tool.”

Finally, there’s the long-tail experience: iteration. Once the novelty wears off, you’re left with a platform.

Builders start swapping servos for quieter ones, strengthening joints, improving cable management, adding a better wrist, or experimenting with

algorithms that smooth transitions. Educators create lesson plans around it. Researchers treat it like a testbed for dexterity and legibility.

And that’s the best outcome: a robot hand that doesn’t just “speak in signs” once for the camera, but keeps teaching peopleabout robotics,

about language, and about designing with humans at the center.