Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Proxy Server Definition in Plain English

- How a Proxy Server Works

- Main Types of Proxy Servers

- Forward Proxy vs Reverse Proxy

- Why Use a Proxy Server?

- Proxy Server Benefits (and Honest Limitations)

- Proxy vs VPN vs Firewall vs NAT

- Common Proxy Security Mistakes

- How to Choose the Right Proxy Server

- How to Implement a Proxy Without Drama

- Practical Examples

- FAQ: Fast Answers

- Conclusion

- Field Experience Notes (About )

If the internet were a busy restaurant, your device would be the customer, the website would be the kitchen, and a proxy server would be the calm, efficient server who says, “I’ll handle this,” then returns with your order. Sometimes that server also checks your ID, filters your requests, speeds up repeat orders, and keeps the kitchen from seeing your home address. Handy, right?

In technical terms, a proxy server is an intermediary that receives a request from a client, then forwards that request to a destination server (or vice versa), and returns the response. That simple middleman role powers huge parts of modern IT: web filtering, content caching, threat control, privacy layers, API gateways, and enterprise traffic policies.

In this guide, you’ll get a practical, no-fluff explanation of proxy servers: what they are, the major types, how they work with HTTP and HTTPS, where they help, where they fail, and how to choose one without accidentally creating a security horror story.

Proxy Server Definition in Plain English

A proxy server is a computer system (or cloud service) that sits between a requester and a resource. Instead of connecting directly to a website or service, a user or application connects to the proxy first. The proxy then relays traffic on the requester’s behalf.

This “in-between” position gives the proxy power to:

- Inspect requests and responses

- Apply access and security policies

- Cache content for faster repeat access

- Mask internal IP details from external systems

- Balance traffic across multiple back-end servers

Think of it as a programmable traffic checkpoint. It can be friendly and helpful, strict and policy-driven, or both before lunch.

How a Proxy Server Works

Step-by-Step: Forward Proxy Flow

- A user device sends a request to a configured proxy.

- The proxy authenticates the user or device (if required).

- The proxy checks rules (allow/deny categories, domains, protocols, time windows, etc.).

- If allowed, the proxy forwards the request to the destination.

- The destination server returns data to the proxy.

- The proxy may scan, log, modify headers, cache, then return the response to the client.

What Changes With HTTPS?

With encrypted traffic, proxies often use tunneling behavior (for example, HTTP CONNECT) so a client can establish a secure path to the destination through the proxy. Enterprise environments may also implement deeper inspection with explicit trust controls, certificates, and policy management.

Step-by-Step: Reverse Proxy Flow

- A user sends a request to a public endpoint (domain/app).

- The reverse proxy receives the request in front of origin servers.

- It applies logic like TLS termination, routing, rate limiting, WAF rules, bot filtering, and caching.

- It forwards traffic to the best back-end server/service.

- The response returns through the reverse proxy to the user.

End users usually don’t realize a reverse proxy is involved. They just notice the app is faster and less likely to explode at peak traffic.

Main Types of Proxy Servers

1) Forward Proxy

Sits in front of clients (users/devices). Common in schools, enterprises, and managed networks for outbound web control, logging, and policy enforcement.

2) Reverse Proxy

Sits in front of servers/apps. Common for load balancing, security controls, TLS offloading, traffic steering, and caching.

3) Transparent Proxy

Intercepts traffic without requiring users to manually configure proxy settings. Often used on managed networks and public access environments.

4) Anonymous / High-Anonymity Proxy

Designed to obscure client-origin information to varying degrees. Important note: “anonymity” claims vary wildly by provider quality, logging behavior, and detection methods.

5) Distorting Proxy

Identifies as a proxy while presenting altered origin details. Used in niche scenarios, though many modern services detect or restrict this behavior.

6) Data Center Proxy

IPs come from hosted infrastructure, usually fast and cost-efficient. Often easier to detect than residential sources.

7) Residential Proxy

Uses IP addresses associated with consumer networks/devices. Can appear more “natural” to websites, but brings ethical and compliance considerations depending on sourcing and consent.

8) HTTP/HTTPS Proxy

Optimized for web protocols and policy logic around HTTP semantics.

9) SOCKS Proxy

Operates at a lower layer and can relay multiple traffic types beyond standard web browsing.

10) Caching Proxy

Stores reusable responses to reduce latency and bandwidth consumption for repeated requests.

11) Secure Web Gateway (SWG-style Proxy)

A policy-rich proxy model that combines filtering, threat protection, and traffic governance for organizational environments.

Forward Proxy vs Reverse Proxy

| Aspect | Forward Proxy | Reverse Proxy |

|---|---|---|

| Protects / Represents | Clients (users/devices) | Servers/services |

| Traffic Direction Focus | Outbound | Inbound |

| Common Goals | Access control, privacy layer, user policy | Performance, security, scalability, reliability |

| Typical Features | URL filtering, user auth, logging | Load balancing, TLS termination, WAF, caching |

| Who Knows It Exists? | Often the organization and sometimes users | Usually invisible to end users |

Why Use a Proxy Server?

Security Control

Proxies can enforce outbound web rules, block known bad categories, and reduce direct exposure of internal systems.

Performance Improvement

Caching and request optimization can lower latency and reduce repetitive origin load.

Operational Visibility

Centralized logging and policy checkpoints simplify monitoring, governance, and incident response.

Scalability for Public Apps

Reverse proxies distribute traffic, support maintenance windows, and protect origin services from traffic spikes.

Access Governance

Teams can enforce role-based access patterns and route users through approved paths (for example, identity-aware access layers).

Proxy Server Benefits (and Honest Limitations)

Benefits

- Centralized policy enforcement

- Reduced origin exposure

- Improved performance through caching

- Flexible traffic shaping and routing

- Better compliance visibility in managed networks

Limitations

- Misconfiguration can break apps, auth flows, or redirects

- A proxy can become a single point of failure without redundancy

- Poor trust handling of forwarded headers creates security risk

- “Free proxy” ecosystems can be risky for privacy and integrity

- Proxy use is not a legal or ethical bypass pass

Proxy vs VPN vs Firewall vs NAT

- Proxy server: Intermediary at application/service layer for selected traffic, often policy-rich.

- VPN: Encrypted tunnel for broader network traffic between device and VPN endpoint.

- Firewall: Rule-based traffic control, usually focused on packet/session policies.

- NAT: Address translation mechanism, not a full security or policy platform by itself.

These are complementary, not mutually exclusive. Mature architectures often combine all four.

Common Proxy Security Mistakes

1) Trusting Client-Origin Headers Blindly

Headers like X-Forwarded-For can be useful, but only when trust boundaries are well-defined. Treating all inbound header values as truth can enable spoofing and logging abuse.

2) Overly Permissive CONNECT Tunnels

Allowing arbitrary destination ports through CONNECT can create abuse paths. Restrict to safe targets and approved ports.

3) Open Proxy Exposure

Publicly reachable, unauthenticated proxies can be quickly abused for malicious traffic and reputation damage.

4) Caching Sensitive Content Incorrectly

Shared caches require correct cache-control behavior. Misapplied caching directives can leak private data or serve stale responses.

5) Ignoring Proxy Health and Failover

If the proxy fails and nothing backs it up, your “high availability” design becomes “high anxiety” in minutes.

How to Choose the Right Proxy Server

Ask these questions before picking tools or providers:

- Do you need to control outbound user traffic, inbound app traffic, or both?

- Is your priority security inspection, speed, privacy, compliance logging, or all of the above?

- Which protocols must be supported (HTTP/HTTPS only or broader transport)?

- How will identity and authentication integrate?

- What are your uptime and failover requirements?

- How will you handle certificate management and trust chains?

- What data retention and jurisdiction rules apply?

- Can your team operate and audit this at scale?

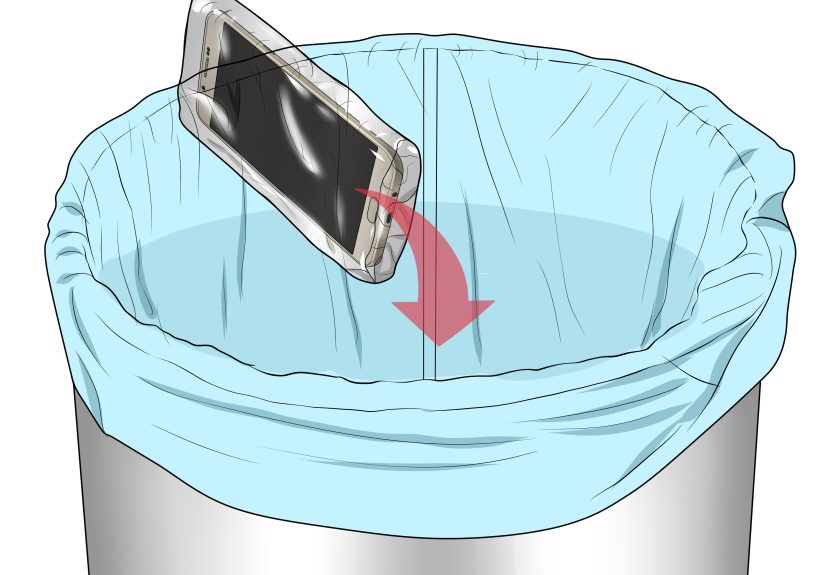

How to Implement a Proxy Without Drama

- Define use case and trust boundaries first.

- Choose architecture (forward, reverse, or layered model).

- Set explicit allow/deny policy baselines.

- Configure authentication and least-privilege access.

- Lock down CONNECT and sensitive egress paths.

- Harden forwarded-header trust logic.

- Tune caching rules for public vs private content.

- Enable health checks, redundancy, and graceful failover.

- Log events with privacy-aware retention settings.

- Test with real traffic patterns, then iterate.

Practical Examples

Example A: School Network

A forward proxy enforces category filtering and time-based rules while giving administrators visibility into outbound browsing patterns.

Example B: E-commerce Platform

A reverse proxy in front of origin services handles TLS, caches static assets, and spreads bursts across back-end clusters to protect checkout reliability.

Example C: Hybrid Enterprise Access

Identity-aware proxy patterns allow controlled access to internal apps without exposing them broadly to the internet.

FAQ: Fast Answers

Is a proxy server the same as a VPN?

No. A proxy typically handles selected traffic flows; a VPN usually tunnels broader device/network traffic.

Can proxy servers improve speed?

Yes, especially with caching and optimized routingbut only when configured correctly for your workload.

Do proxies guarantee anonymity?

No. They can reduce direct exposure, but anonymity depends on provider behavior, logging, browser fingerprinting, and detection controls.

Do small teams need reverse proxies?

Often yes. Even modest apps benefit from centralized TLS, request routing, and protective controls.

Conclusion

A proxy server is not just a “technical middleman.” It is a strategic control point. Done well, it improves performance, strengthens security posture, and simplifies traffic governance. Done badly, it creates blind spots and brittle architecture.

Start with one clear use case, design trust boundaries carefully, and treat proxy configuration as security infrastructurenot a quick checkbox. If your internet stack is a city, the proxy is both traffic light and gatekeeper. Keep it smart, monitored, and boringly reliable.

Field Experience Notes (About )

Across real-world IT operations, proxy projects usually begin with a simple goal“block bad traffic” or “speed up the site”then quickly grow into architecture decisions that affect security, availability, compliance, and user happiness. One repeated pattern is that teams underestimate how many systems quietly depend on original headers, hostnames, and redirect behavior. A reverse proxy goes live, traffic flows, and then authentication callbacks fail, cookies break, or absolute URLs start pointing to internal domains. The fix is rarely magical; it’s usually careful header handling, host preservation, and environment-specific testing before rollout.

Another common experience comes from forward proxies in organizations with remote users. At first, policy control improves quickly: better visibility, cleaner outbound filtering, fewer risky destinations. Then edge cases appear. Developer tools, package managers, and third-party APIs may require specific exceptions. Teams that succeed avoid one giant “allow all” rule and instead build tiered, documented policy sets: baseline rules for everyone, scoped exceptions for teams, short expiration dates for temporary access, and automatic review cycles. That operational discipline prevents policy drift and keeps the proxy useful instead of becoming a legacy bypass machine.

Performance-focused proxy deployments often teach a valuable lesson: caching helps only when cache strategy matches content behavior. Static assets (images, scripts, versioned files) are usually easy wins. Dynamic or personalized responses are where mistakes happen. Several teams discover that overly broad caching causes stale dashboards, cross-user content confusion, or support tickets that begin with, “I swear I changed that setting.” Mature teams solve this with explicit cache-control policies, separation of public vs private responses, and purge workflows tied to deployment pipelines. In other words, cache is not a switch; it’s a contract.

Security teams also learn quickly that proxy logs are powerful but sensitive. Logging everything forever sounds attractive during incident response planning, but indiscriminate retention can create privacy and compliance headaches. Teams that balance both sides define what must be logged, who can access logs, how long records are retained, and how sensitive fields are minimized or masked. They also treat header-based client identification carefully, especially in multi-proxy chains, because trusting unvalidated origin headers can poison analytics and rate-limiting logic.

On the reliability side, one of the biggest “aha” moments is realizing the proxy itself is critical infrastructure. If it fails, everything behind it fails. High-performing teams design for graceful degradation: multiple proxy instances, health checks, rolling deployments, and clear fallback paths. They test failure scenarios intentionallycertificate expiration, upstream timeout spikes, DNS issues, and sudden traffic burstsbefore users test them by surprise.

Finally, there’s the human side. Proxy projects work best when network, security, platform, and application teams collaborate early. When one team “owns” the proxy in isolation, blind spots appear. When teams share runbooks, dashboards, and incident drills, the proxy becomes what it should be: a dependable control plane for traffic, not a mysterious box everyone blames at 2:00 a.m.