Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Does It Mean to Be Ticklish?

- The Two Types of Tickling: Knismesis vs. Gargalesis

- Why Are Some People More Ticklish Than Others?

- What Happens in the Brain When You’re Tickled?

- Why Can’t You Tickle Yourself?

- Why Did Humans Evolve to Be Ticklish?

- Can You Stop Being Ticklish?

- Is Being Ticklish Good or Bad?

- Real-Life Experiences: Living With (or Without) Ticklishness

- Bottom Line

If you’ve ever dissolved into helpless laughter when someone goes for your ribs or feet, you’ve probably wondered, why am I so ticklish? And why can strangers barely pat your shoulder while your best friend knows the exact spot that turns you into a giggling puddle on the floor?

Ticklishness sounds simple, but it’s actually a strange mix of touch, brain chemistry, emotion, and even evolution. Scientists still don’t have all the answers, but what we do know is surprisingly fascinating (and yes, slightly weird).

In this in-depth guide, we’ll break down why people are ticklish, what’s happening in your nervous system when you laugh and squirm, and what you can do to reduce – or at least manage – that intense tickle response.

What Does It Mean to Be Ticklish?

Tickling is the sensation you feel when someone (or something) touches your skin in a way that triggers involuntary reactions – like laughing, squirming, pulling away, or shouting, “Stop!” even as you keep laughing. For many people, ticklishness shows up in a few classic places:

- Ribs and sides

- Armpits

- Neck and collarbone area

- Feet and toes

- Inner thighs and behind the knees

Not everyone is ticklish, and people who are ticklish aren’t ticklish in the same spots. Some find tickling unbearable; others only react when they’re relaxed or with certain people. That alone tells us there’s more going on than just “weird touch.”

The Two Types of Tickling: Knismesis vs. Gargalesis

Science actually has names for different kinds of tickling (because of course it does).

1. Knismesis: The “Something’s Crawling on Me” Tickle

Knismesis is the light, feathery kind of tickle – like a hair brushing your skin, a bug crawling on your arm, or the super soft touch that makes you shiver but doesn’t always make you laugh. It’s more of an itching or tingling sensation than a laugh-out-loud experience. Researchers think this type of tickling evolved as a warning system to help us detect insects or parasites on our skin so we can flick them away.

2. Gargalesis: The “I Can’t Stop Laughing” Tickle

Gargalesis is the intense, laugh-inducing tickling most of us think of: poking or squeezing your ribs, wiggling fingers under your arms, or attacking the soles of your feet. This type usually requires:

- Firm, repetitive pressure

- Specific “tickle spots” on the body

- Another person (you can’t really do this one to yourself)

Gargalesis is more complex and seems to happen mostly in humans and other primates. It’s strongly tied to social interaction, emotion, and the element of surprise.

Why Are Some People More Ticklish Than Others?

Ever notice that some people shriek with laughter the second you <emthreaten to tickle them, while others barely flinch? Ticklishness varies from person to person because it’s influenced by several factors:

- Sensitivity of the skin and nerves: People with more sensitive nerve endings or heightened tactile sensitivity may feel tickles more intensely.

- Personality and mood: When you’re relaxed, playful, or trusting, you’re often more ticklish. If you’re stressed, guarded, or annoyed, the tickle response may fade.

- Relationships and trust: Many people are more ticklish with close friends, partners, or family than with strangers. Emotional context matters.

- Past experiences: If tickling was playful and positive in childhood, you might lean into it. If it was used in a way that felt overwhelming or out of control, your body might react with anxiety instead of laughter.

So ticklishness isn’t just a physical thing – it’s also social and emotional.

What Happens in the Brain When You’re Tickled?

Tickling is a sensory rollercoaster for your nervous system. When someone tickles you, here’s a simplified version of what’s going on:

- Your skin senses the touch. Special nerve endings in the skin send signals through your nerves to your spinal cord and up to the brain.

- The somatosensory cortex processes the touch. This region helps your brain figure out where you’re being touched and what kind of touch it is.

- The anterior cingulate cortex and other emotional areas get involved. These regions process whether that sensation is pleasant, playful, or threatening, and they’re closely connected to laughter and emotional reactions.

- The hypothalamus kicks in. This small but powerful region is involved in fear, defense, and the fight-or-flight response. Some research suggests that intense tickling lights up the same systems that respond to threat – which may explain why tickling makes you laugh and feel slightly panicked at the same time.

The result? A mix of giggles, squirming, and that “I hate this but also can’t stop laughing” feeling that makes tickling such a strange experience.

Why Can’t You Tickle Yourself?

This is one of the biggest tickle mysteries, and science actually has a clever answer. When you move your own hand to touch your body, your brain makes a prediction of what that touch will feel like. This prediction is created using a signal called an efference copy – basically, a copy of your own movement command.

Because your brain already “knows” what’s coming, it tones down the sensation. That’s why:

- Scratching your own side doesn’t feel as ticklish as when someone else does it.

- Lightly running your fingers on your own feet usually just feels like regular touch.

With external tickling, you don’t fully predict the timing, speed, or pressure of the touch, so your brain doesn’t dampen the sensation the same way. The surprise factor stays high – and so does the tickle response.

Why Did Humans Evolve to Be Ticklish?

Scientists haven’t agreed on one single reason, but several theories try to explain why people are ticklish.

1. Defense and Protection

Many of the most ticklish spots – like the neck, ribs, and belly – are also some of the most vulnerable areas of the body. One leading theory suggests that ticklishness evolved as a defense mechanism. A strong reaction to touch in these areas may have helped our ancestors quickly protect themselves from threats or attacks.

In this view:

- Knismesis (light, itchy tickling) helps detect small threats like insects or parasites on the skin.

- Gargalesis (deep, laugh-inducing tickling) encourages fast, protective movements and teaches the body to guard vulnerable spots.

2. Social Bonding and Play

Another major theory is that tickling supports social bonding. Parents often tickle babies and young kids during play, and those giggles can strengthen emotional connections. In primates, similar playful touching and tickling-like interactions are part of social grooming and bonding.

From this perspective, tickling:

- Reinforces trust and closeness in safe relationships.

- Creates shared laughter, which releases feel-good chemicals like endorphins.

- Helps children learn social cues – like when it’s okay to continue play and when to stop.

3. A Training Ground for Reflexes

Some experts suggest that tickling might help train the body’s defensive reflexes. Think of rough-and-tumble play between siblings or friends: tickling often leads to dodging, blocking, twisting, and guarding sensitive areas. Over time, that playful combat may sharpen reflexes that could be useful in real-world situations.

These theories aren’t mutually exclusive. Ticklishness might serve more than one function – part defense, part social glue, part nervous-system boot camp.

Can You Stop Being Ticklish?

If you’re extremely ticklish, you might not care about the evolutionary advantages. You just want to stop flailing every time someone gets near your ribs. The truth is, you probably can’t completely erase ticklishness, but you may be able to reduce or manage it.

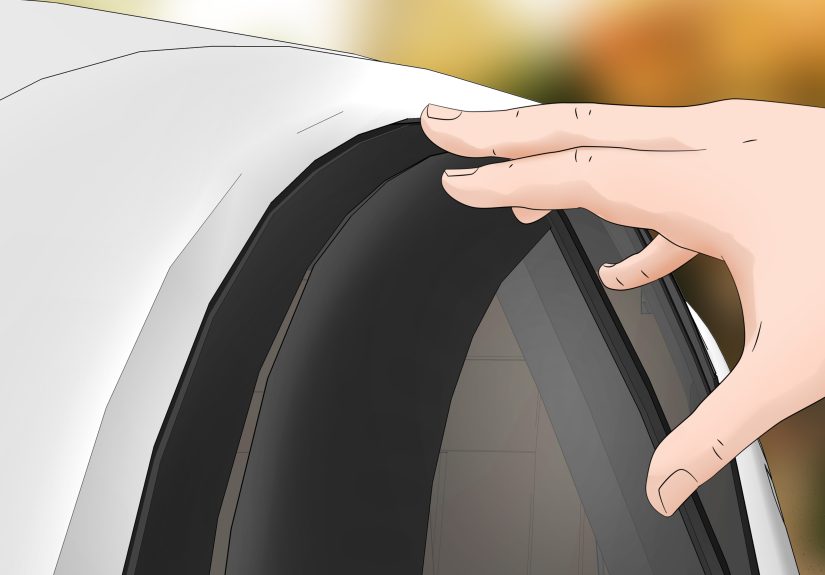

1. Use the “Hand on the Tickler’s Hand” Trick

One practical strategy described by educators and health writers is simple: when someone tries to tickle you, place your hand on their hand while they’re doing it. This does two things:

- Your brain gets better at predicting the sensation because you’re now partially controlling the movement.

- The tickle feels more like self-touch and less like an unpredictable external attack.

For some people, this noticeably reduces that overwhelming, involuntary laughter and squirming.

2. Breathe and Relax (Seriously)

Tickling tends to be worse when you’re already tense or anticipating it. That anticipation alone can make your nervous system more reactive. To dial it down:

- Focus on slow, deep breaths when you feel tickles coming on.

- Try relaxing your stomach, shoulders, and jaw instead of clenching them.

- Mentally remind yourself that you’re safe and in control.

It won’t make you completely immune, but reducing anxiety can soften the response.

3. Desensitize Ticklish Areas Gradually

Some people find that repeated, gentle exposure helps. For example:

- Gently massage or press on your own ticklish spots – like your feet, sides, or neck – in a firm but not ticklish way.

- Use lotion or a massage tool and focus on steady pressure rather than light fluttery touch.

- Over time, your brain may start interpreting touch in those areas as more neutral and less threatening or startling.

This isn’t guaranteed, but it can help some people feel less hypersensitive.

4. Set Clear Boundaries

This one isn’t about your nerves – it’s about the people around you. If tickling makes you uncomfortable, anxious, or triggered, it’s completely okay to say so clearly and firmly:

- “Tickling really overwhelms me. Please don’t do it.”

- “I know it looks funny, but I actually hate being tickled.”

Healthy relationships respect boundaries. You don’t owe anyone a performance just because they think your ticklishness is entertaining.

5. When Ticklishness Changes Suddenly

If you notice a sudden change – like you used to be very ticklish and now you’re not, or the sensation feels painful or very different – talk with a healthcare professional. While ticklishness itself isn’t a medical condition, changes in sensation can sometimes be connected to nerve or neurological issues that deserve attention.

Is Being Ticklish Good or Bad?

Being ticklish isn’t inherently good or bad – it’s just one way your nervous system reacts to certain types of touch. For some people, it’s a fun part of playful connection. For others, it’s overwhelming or even distressing.

What matters most is consent and comfort. Tickling should always stop the moment someone says “no,” “stop,” or even just looks uncomfortable. Laughter during tickling isn’t always a sign that someone is enjoying it – it’s often part of the reflex itself.

When handled kindly and respectfully, tickling can be:

- A playful way to connect with kids, partners, and close friends

- A window into how amazingly complex our brains and nerves really are

- A reminder that even ordinary sensations have deep biological and emotional roots

Real-Life Experiences: Living With (or Without) Ticklishness

For something so small and silly, being ticklish can shape a surprising number of life moments. Here are a few common experiences many people can relate to – and what they reveal about the way ticklishness works in everyday life.

The “Don’t You Dare” Standoff

Picture this: you’re on the couch, someone wiggles their fingers in the air and says, “I’m gonna get you.” You immediately curl up, start laughing before they even touch you, and maybe roll off the couch in self-defense. No tickling has actually happened yet – but your brain and body have already jumped to high alert.

This moment shows how much anticipation shapes the tickle response. Your nervous system remembers exactly what those wiggling fingers feel like, and even the threat is enough to launch you into a half-panicked, half-amused reaction. It’s a perfect example of how memory and emotion amplify simple touch.

The Foot Massage Problem

Plenty of people dream about a relaxing pedicure or a spa day foot massage… until they remember that their feet are so ticklish they practically kick on reflex. For some, even a light touch at the salon can trigger an uncontrollable jerk or burst of laughter that feels anything but peaceful.

Over time, some people learn to manage this by communicating clearly with the person doing the massage: “My feet are super ticklish, so please use firmer pressure.” Steady, firm touch is less likely to trigger the classic ticklish sensation than light, unpredictable strokes. Many eventually discover they can enjoy foot care as long as they stay relaxed and the person touching them moves confidently instead of tentatively.

Tickling and Kids: Fun vs. Overwhelming

Tickling is practically a language in many families: parents tickling toddlers, siblings starting tickle wars, kids collapsing into giggles on the carpet. Used gently and respectfully, it can be a bonding ritual filled with shared laughter and affection.

But there’s another side to this, too. Because tickling can activate the body’s fight-or-flight systems, a child might laugh uncontrollably while actually feeling overwhelmed or out of control. Many adults remember times when a tickle game went on a little too long and shifted from fun to distressing.

The big lesson here? Even if someone is laughing, it’s still important to check in: “Is this fun? Do you want me to stop?” Teaching kids that their “no” matters – even in playful moments – helps build body autonomy and trust.

The “I Used to Be Ticklish, Now I’m Not” Story

Some people notice that their ticklishness changes over time. Maybe you were extremely ticklish as a child and now barely react, or certain spots don’t bother you anymore. A few different things may be going on:

- You’ve become less sensitive in certain areas due to repeated touch or massage.

- Your brain no longer interprets those touches as surprising or threatening.

- Your emotional reactions to tickling have shifted – maybe you’re less playful with it or have clearer boundaries.

In some cases, bigger changes in sensation can be a reason to check in with a healthcare provider, but gradual changes in ticklishness are often just part of how your nervous system and emotional life evolve together.

Owning Your Boundaries

For people who really dislike being tickled, one of the most powerful “prevention strategies” is social, not neurological: learning to say no early and clearly. That might mean telling family or friends, “I know I laugh, but I really don’t enjoy being tickled,” or setting a rule that tickling stops immediately when you say a safe word.

Over time, many people find that once they know they’re in control of when tickling starts and stops, it feels less like something being done to them and more like just another playful option – one they can opt into or out of based on their mood.

Bottom Line

So, why are people ticklish? It’s a complicated blend of sensitive skin, busy nerve pathways, brain regions that handle both touch and emotion, plus a dash of evolution and social bonding. Ticklishness protects us, connects us, and occasionally embarrasses us in public when someone grabs our sides unexpectedly.

You may never be able to completely turn off your tickle response, but understanding what’s happening inside your body – and knowing a few tricks to reduce it – can make you feel more in control. Whether you’re someone who loves playful tickling or someone who would be perfectly happy to never be poked in the ribs again, your reaction is valid. Your nervous system is just doing its quirky, complicated thing.