Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Are Valence Electrons (and Why Do They Matter)?

- The Fast Method: Use the Periodic Table Group (Main-Group Elements)

- Examples: Main-Group Elements (Where the Shortcut Shines)

- What If Your Periodic Table Uses A/B Groups?

- The Reliable Backup Method: Use Electron Configuration

- Transition Metals: Why the Shortcut Gets Tricky

- Lanthanides and Actinides: The “Extra Credit” Zone

- Quick Memory Tricks That Actually Help

- Practice Checks (With Answers)

- Common Mistakes (So You Can Avoid Them Like a Pro)

- Conclusion: Your 10-Second Valence Electron Workflow

- Experiences Learning to Find Valence Electrons (The Real-Life Version)

The periodic table isn’t just a classroom poster that slowly fades in the sun while you forget where you put your pencil.

It’s a cheat sheet for how atoms behaveespecially when it comes to valence electrons, the “outer-ring” electrons

that decide whether an element is chill, clingy, or ready to start chemical drama with the element sitting next to it.

In this guide, you’ll learn how to find valence electrons quickly using the periodic table, when that shortcut works perfectly,

and when chemistry makes things “interesting” (looking at you, transition metals). You’ll also get examples, a few memory tricks,

and practice-style checks so you can be confidentnot just lucky.

What Are Valence Electrons (and Why Do They Matter)?

Valence electrons are the electrons in an atom that are most available for bonding and chemical reactions.

For many elements (especially the main-group elements), these are the electrons in the outermost energy level.

They’re the reason sodium loves giving away an electron, chlorine loves adopting one, and carbon basically refuses to commit to a single bonding style.

Valence electrons help you predict:

- Reactivity: Why some elements explode in water and others just sit there looking fancy.

- Bonding patterns: How many bonds an element tends to form (Lewis structures become way less scary).

- Ion charges: Why Na becomes Na+ and O becomes O2− in many compounds.

- Periodic trends: Similar behavior within columns (groups) starts to make sense.

The Fast Method: Use the Periodic Table Group (Main-Group Elements)

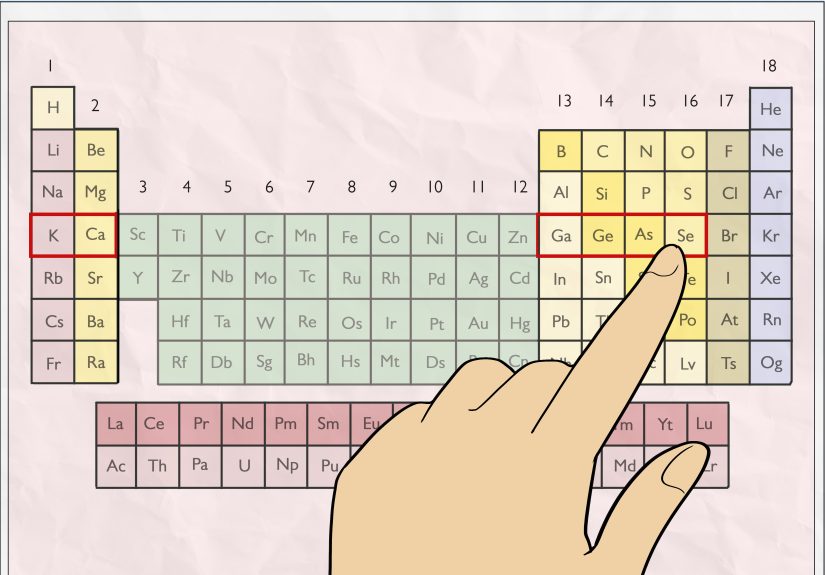

Here’s the headline: for main-group elements (the s- and p-block: Groups 1–2 and 13–18),

the number of valence electrons is strongly tied to the group number.

Step-by-Step: Finding Valence Electrons Using Group Numbers

- Find your element on the periodic table.

- Identify its group (column) using the modern 1–18 numbering system.

- Convert group → valence electrons using the rules below (with one famous exception).

Main-Group Valence Electron Rules

| Group | Common Name | Valence Electrons (Typical) | Quick Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alkali metals | 1 | Very reactive metals (H is special, but still has 1 valence electron) |

| 2 | Alkaline earth metals | 2 | Often form 2+ ions |

| 13 | 3 | Think “13 → 3” | |

| 14 | Carbon group | 4 | Carbon is the bonding overachiever |

| 15 | Nitrogen group | 5 | Often form 3 bonds in neutral molecules |

| 16 | Oxygen group | 6 | Often form 2 bonds (octet rule patterns) |

| 17 | Halogens | 7 | One electron short of a full octet |

| 18 | Noble gases | 8 (except He) | Helium is the exception: it has 2 valence electrons |

The helium exception: Helium is in Group 18, but it only has 2 valence electrons because its outermost (and only) shell is the first shell,

which maxes out at 2 electrons. So yeschemistry lets you learn a perfect pattern and then immediately reminds you it’s in charge.

Examples: Main-Group Elements (Where the Shortcut Shines)

Example 1: Sodium (Na)

Sodium is in Group 1, so it has 1 valence electron.

That’s why sodium often forms Na+: it’s easier to lose one electron than to collect seven more.

Example 2: Oxygen (O)

Oxygen is in Group 16, so it has 6 valence electrons.

It tends to form two bonds (or gain two electrons to form O2−) to reach a stable octet-like arrangement.

Example 3: Chlorine (Cl)

Chlorine is in Group 17, so it has 7 valence electrons.

It’s famously “one electron away” from a full valence shell, which explains why it so often forms Cl−.

Example 4: Carbon (C)

Carbon is in Group 14, so it has 4 valence electrons.

That “4” is the reason carbon can form four bonds in many stable moleculeshello, organic chemistry.

What If Your Periodic Table Uses A/B Groups?

Most modern periodic tables use Groups 1–18. Some older or alternative tables show A/B labels (like 1A, 2A, 3A…).

If you see “A groups,” those typically refer to the main-group elements where the “group number = valence electrons” shortcut is intended to work.

If your table is confusing, stick to this reliable rule of thumb: for the main group, you want the columns on the far left (Groups 1–2)

and the far right (Groups 13–18). That’s your valence-electron sweet spot.

The Reliable Backup Method: Use Electron Configuration

When group shortcuts aren’t enough (or when you want deeper understanding), use electron configuration.

The idea is simple: for main-group elements, valence electrons are the electrons in the highest principal energy level (highest n).

How to Count Valence Electrons from an Electron Configuration

- Write the electron configuration (or use noble-gas shorthand).

- Find the largest n (the outermost energy level).

- Count the electrons in that level’s s and p orbitals.

Example: Phosphorus (P)

Phosphorus: [Ne] 3s2 3p3

Highest n is 3. Valence electrons = 2 + 3 = 5.

That matches the periodic table shortcut (Group 15 → 5 valence electrons). Nice when life agrees with itself.

Transition Metals: Why the Shortcut Gets Tricky

Transition metals (Groups 3–12) live in the d-block, and they don’t always behave like the neat main-group pattern.

If you’ve ever asked, “How many valence electrons does iron have?” and gotten multiple answers, congratulationsyou’ve met chemistry’s favorite party trick.

Here’s the practical reason: in transition metals, the ns and (n−1)d electrons can both participate in bonding,

and the energy difference between those orbitals can be small. That contributes to variable oxidation states and more complicated bonding behavior.

A Practical Way to Handle Transition Metals (Without Losing Your Mind)

Decide what you’re trying to dobecause “valence electrons” can mean slightly different things depending on the context:

- For basic bonding/chem behavior: consider the outer s plus the d electrons that can participate (often ns + (n−1)d).

- For common ion formation: many transition metals lose the ns electrons first, then some d electrons (helpful for predicting charges).

- For Lewis dot structures in intro chemistry: you usually focus on main-group elements anyway, because transition-metal Lewis structures can get advanced fast.

Example: Iron (Fe)

Iron’s electron configuration is often written as [Ar] 4s2 3d6.

Depending on the context, you may consider:

- 2 valence electrons (the 4s electrons) for a simplified “outermost shell” view, or

- 8 valence electrons (4s2 + 3d6) for a bonding/transition-metal view.

The “right” answer depends on the question being asked. That’s not you failingthat’s chemistry being a language with dialects.

Example: Copper (Cu)

Copper is famous for an electron configuration exception: [Ar] 4s1 3d10.

This helps explain why copper commonly forms Cu+ and Cu2+ in different compounds.

Lanthanides and Actinides: The “Extra Credit” Zone

The f-block elements (lanthanides and actinides) add another layer: f electrons can matter, too.

If you’re in a general chemistry course, you’ll often handle these with electron configurations and common oxidation states,

rather than relying on a quick periodic-table valence rule.

Quick Memory Tricks That Actually Help

Trick 1: “1–2 on the left, 3–8 on the right”

Groups 1–2 have 1–2 valence electrons. On the right side, Groups 13–18 map to 3–8 valence electrons (13→3, 14→4, etc.).

Just remember helium is the exception with 2.

Trick 2: Count Across a Period (Main Group)

For the main-group elements, valence electrons generally increase as you move left to right across a row:

1, 2, then (after the transition metals) 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

Trick 3: Lewis Dots Are Just Valence Electrons Wearing Hats

If you’re drawing Lewis dot structures, you’re literally placing valence electrons as dots around the element symbol.

Find the valence electrons first, then dot away.

Practice Checks (With Answers)

1) How many valence electrons does magnesium (Mg) have?

Mg is in Group 2 → 2 valence electrons.

2) How many valence electrons does bromine (Br) have?

Br is in Group 17 → 7 valence electrons.

3) How many valence electrons does silicon (Si) have?

Si is in Group 14 → 4 valence electrons.

4) What about neon (Ne)?

Ne is in Group 18 → 8 valence electrons (full valence shell).

Common Mistakes (So You Can Avoid Them Like a Pro)

-

Mistake: Using the group shortcut on transition metals.

Fix: Use electron configuration and the context of the question. -

Mistake: Forgetting helium is weird (in a very stable way).

Fix: Remember: Group 18, but only 2 electrons in its first shell. -

Mistake: Mixing up “valence electrons” and “valency.”

Fix: Valence electrons are electrons; valency is a bonding capacity concept (related, but not identical). -

Mistake: Assuming an element’s most common ion charge is always the valence electron count.

Fix: Use valence electrons to predict trends, but real compounds can be more nuanced.

Conclusion: Your 10-Second Valence Electron Workflow

If you want a fast, reliable process, use this:

- Is it in Groups 1–2 or 13–18? Use the group shortcut (13→3, 14→4… 18→8, except He→2).

- Is it a transition metal? Use electron configuration and the context (bonding vs ion formation).

- Need to double-check? Count valence electrons from the highest n level (main group) or ns + (n−1)d (transition metals, context-dependent).

Once you get comfortable, the periodic table starts feeling less like a wall decoration and more like a decoder ring for chemistry.

And yeschemistry still has exceptions. But now you’ll recognize them as features, not ambushes.

Experiences Learning to Find Valence Electrons (The Real-Life Version)

If you’ve ever stared at the periodic table like it personally insulted you, you’re not alone. One of the most common learning experiences with valence electrons

is the “Wait… that’s it?” moment. At first, it feels like you need advanced math, special goggles, and maybe a minor in quantum physics.

Then someone shows you the group-number shortcut for main-group elementsand suddenly you’re counting valence electrons faster than you can open your calculator app.

That early confidence boost is real, and it’s usually what gets students comfortable enough to tackle Lewis structures without panic.

The next experience is almost universal: you get used to the clean pattern, and then helium shows up like a polite little rule-breaker.

You learn that Group 18 usually means 8 valence electrons, and helium smiles and says, “I have 2.” This is actually a helpful moment,

because it teaches an important chemistry mindset: patterns are powerful, but the reason behind the pattern matters even more.

Once you understand that the first energy level only holds two electrons, helium stops feeling like a random exception and starts feeling logical.

After that, many learners hit the transition-metal wall. You try to apply the same shortcut to iron or copper and the answers get messyfast.

This is where students often feel like they “forgot chemistry,” but what’s really happening is they’ve moved from a tidy beginner rule into a more realistic view of electrons.

A practical experience that helps here is shifting your question from “What is the valence electron number?” to “What does this problem want me to predict?”

If the goal is a basic Lewis structure or an octet-rule trend, you’ll mostly be working with main-group elements anyway.

If the goal is oxidation states or ion charges in transition metals, electron configuration and common ionic behavior become more useful than a single fixed valence count.

A lot of people get better by building small habits: circling the element’s group number, writing the quick mapping (1, 2, 3–8) in the margin,

and doing a “sanity check” with electron configuration for a couple of examples. In classroom settings, students often report that the mapping sticks best when paired

with repeated mini-practice: “Group 16? That’s 6.” “Group 14? That’s 4.” It becomes reflexivelike knowing a stop sign means stop, not “pause and negotiate.”

Another common experience is using Lewis dot structures as feedback: if you place the dots and it doesn’t match the expected bonding behavior (like oxygen with 6),

you catch mistakes early.

Finally, there’s the satisfying “I can explain it” moment. When you can teach someone else the shortcut and also explain why it works

(outermost electrons, similar properties in a group, octet trends), you’re past memorization and into real understanding.

That’s the point where the periodic table stops being a chart you look up and starts being a tool you can usequickly, confidently, and with fewer surprises.

(Except maybe for transition metals. They’ll always keep a little mystery. It’s their brand.)