Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Japanification” Actually Means

- How Japan Ended Up There: A Speed-Run Through the “Lost Decades”

- Why People Think the U.S. Might Be “Japanifying”

- But Here’s the Catch: The U.S. Doesn’t Look Very Japanese Right Now

- Key Differences That Could Keep the U.S. From Full “Japanification”

- A Practical “Japanification” Checklist: What to Watch in the U.S.

- If the U.S. “Japanifies,” What Would It Feel Like?

- So… Is America Turning Japanese?

- Experience Appendix: of “Japanification” in Everyday Life

- SEO Tags

If you’ve seen the phrase “the U.S. is turning Japanese,” relaxthis isn’t about swapping burgers for bento (or

suddenly becoming fluent in polite bowing etiquette). In economics, it’s shorthand for something much less

cinematic and much more spreadsheet-y: the fear that America could drift toward Japan-style

conditionsslower growth, persistently low inflation, lower “neutral” interest rates,

and a government that runs high debt without an immediate bond-market tantrum.

Economists often call this “Japanification”. It’s not a destiny, and it’s not a moral failing. It’s a

particular mix of demographics, policy choices, and economic momentum that can make an economy feel like it’s

moving through molassesquietly, steadily, and with fewer fireworks than anyone ordered.

What “Japanification” Actually Means

“Japanification” is a label for a cluster of trends that showed up in Japan after its late-1980s asset bubble burst:

long stretches of weak demand, subdued inflation (and sometimes deflation), very low interest rates,

and repeated attempts to restart growth through monetary easing and fiscal support. Over time, these conditions can

make borrowing cheap, saving unrewarding, and policy choices… awkward.

The basic mechanics (in plain English)

- Aging population can slow labor-force growth and change spending patterns.

- Lower demand can keep inflation mild, which encourages lower interest rates.

- Low rates can inflate asset prices, support “zombie” firms, and make debt easier to carry.

- High debt becomes less scary when interest costs stay manageablebut riskier if rates rise later.

The “turning Japanese” question, then, is really: Is America sliding toward a world where low inflation and lower

interest rates dominate again, growth feels modest, and the big economic story becomes managing aging and debt?

How Japan Ended Up There: A Speed-Run Through the “Lost Decades”

Japan’s story isn’t a single switch flipping from “boom” to “bust.” But a few repeating themes show up in most

serious summaries:

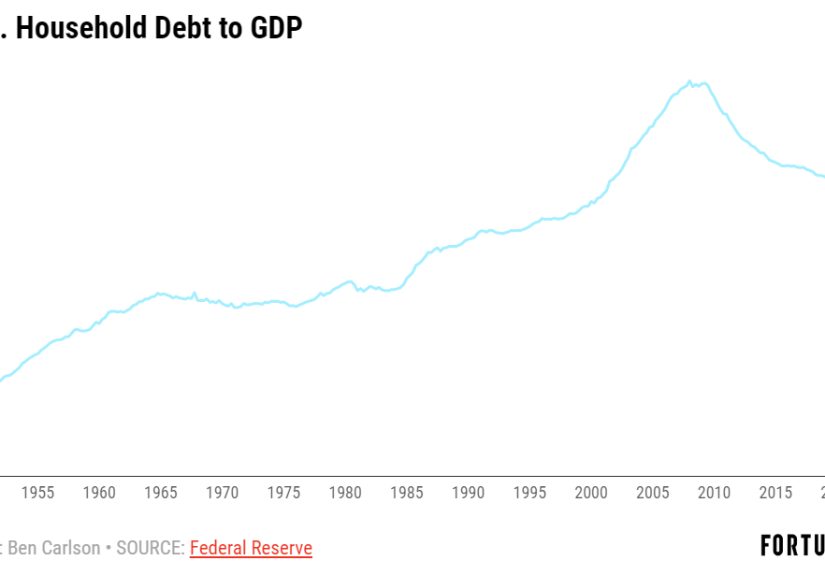

1) Asset bubbles and financial stress can leave long shadows

After Japan’s bubble era ended, the clean-up of balance sheets and banking problems weighed on investment and

confidence. When private sectors focus on paying down debt instead of taking new risks, growth can stay subdued

longer than anyone expects.

2) Low inflation can become self-reinforcing

Once households and firms come to expect low inflation, they behave in ways that keep it lowwage bargaining gets

conservative, price hikes become harder, and monetary policy has to work overtime just to reach a normal 2% target.

3) Central banks eventually run into the “low-rate wall”

When policy rates are near zero, central banks use other toolslarge-scale asset purchases, forward guidance, and

(in Japan’s case) yield curve control. Japan’s central bank famously used aggressive easing for years, including a

framework that explicitly targeted parts of the government bond yield curve.

4) Fiscal support grows as the society ages

Aging increases healthcare and retirement pressures. Combined with years of trying to stabilize growth, this helps

explain why Japan carried large public debt levels without the kind of sustained inflation surge people might assume

is automatic.

Why People Think the U.S. Might Be “Japanifying”

The argument usually isn’t that America will copy Japan step-for-step. It’s that the U.S. is developing a similar

backdropespecially aging and high debtwhile also living in a world where long-run interest rates may

be lower than they used to be.

Clue #1: America is aging (and it’s not subtle)

The U.S. is getting older fast. Census data show the 65+ population has been rising while the under-18 population

has been edging down in recent years, and in many places older adults now outnumber children. An older population

can mean slower labor-force growth unless productivity rises or immigration fills the gap.

Aging doesn’t guarantee stagnation. But it can tilt an economy toward slower baseline growthespecially if fewer

workers are supporting more retirees, and if policy doesn’t adapt.

Clue #2: Public debt is on a steep path

Japan’s “signature” in macro debates is often high government debt carried for a long time. The U.S. is not Japan,

but U.S. debt dynamics are increasingly part of the conversation. Budget projections have federal debt held by the

public rising markedly over the next decade, reaching levels that would surpass prior U.S. historical peaks.

Big debt doesn’t automatically cause a crisisespecially if nominal growth holds up and interest costs remain

manageable. But it can narrow policy flexibility, particularly in downturns.

Clue #3: The long-run “neutral” rate may still be low

Even after the inflation shock of the early 2020s, many analysts and policymakers argue that deeper forceslike

demographics and productivity trendsstill pull the long-run neutral rate (often called “r-star”) downward. If that’s

right, then once inflation cools, interest rates may settle lower than the pre-2008 “normal” people remember.

Clue #4: The U.S. has already used some Japan-style tools

America isn’t new to unconventional policy. After 2008 and again during the pandemic era, the Federal Reserve used

large-scale asset purchases and other measures that looked (at least in silhouette) like Japan’s toolkit: trying to

ease financial conditions when conventional rate cuts weren’t enough.

But Here’s the Catch: The U.S. Doesn’t Look Very Japanese Right Now

If “Japanification” means persistent very low inflation and near-zero interest rates, today’s U.S. snapshot is a

mixed bag.

Inflation isn’t goneit’s just calmer

Recent U.S. inflation readings have been much closer to the Federal Reserve’s 2% goal than during the peak of the

post-pandemic surge, but they’re not “Japan-low” either. The latest data show headline inflation running in the

high-2% range year over year, with core inflation close by.

Policy rates are not near zero

The federal funds target range in mid-January 2026 sits in the mid-3% rangefar above the zero-rate world that

defined much of Japan’s policy environment for years. Longer-term U.S. yields are also meaningfully positive,

reflecting a market that still prices in real returns and risk.

Growth has been more resilient than the “stagnation” story suggests

U.S. GDP growth has not been anemic across the board. Recent quarters have shown solid momentum at times,

reminding everyone that the American economy can still surprise people who wrote the “slow forever” script too

early.

Key Differences That Could Keep the U.S. From Full “Japanification”

1) Immigration and population dynamics

Japan has faced extremely rapid aging with comparatively limited immigration. The U.S. has more demographic

“shock absorbers,” including immigration and a historically higher fertility rate (even if it has fallen).

That matters because labor supply is a growth enginewhen it’s available.

2) Economic flexibility

America’s labor markets, capital markets, and business formation have traditionally been more fluid than Japan’s.

That flexibility can help the U.S. reallocate workers and capital toward new industries fasterespecially in tech,

energy, and services.

3) The dollar’s global role and demand for safe assets

The U.S. benefits from unusually strong global demand for dollar assets, including Treasuries. That can hold down

borrowing costs and support financial stabilitythough it’s not a magic shield against bad policy or weak growth.

4) Japan itself is changing

It’s also worth noting that Japan has not stayed frozen in one policy posture. The Bank of Japan has adjusted its

stance in recent years, including ending major components of its ultra-loose framework. So even the “Japan model”

isn’t a single permanent template.

A Practical “Japanification” Checklist: What to Watch in the U.S.

If you want to know whether America is drifting toward Japan-style macro conditions, watch trends, not headlines.

Here are the signposts that matter most:

Inflation expectations

The Japan scenario becomes more likely when the public starts to believe inflation will stay low indefinitely.

Once expectations anchor too low, pushing inflation back up to target can be surprisingly difficult.

Real interest rates and the yield curve

Pay attention to real yields (inflation-adjusted returns), not just nominal rates. A persistent slide in real yields,

combined with subdued inflation, can signal a lower-growth, higher-savings environment.

Debt service costs

High debt is more manageable when rates are low and growth is steady. Trouble starts when interest costs rise faster

than the economy’s ability to pay themespecially if political gridlock blocks fiscal adjustments.

Productivity growth

Productivity is the cheat code. If the U.S. can raise output per worker through innovation and investment, it can

offset demographic drag. If productivity stays weak, aging matters more.

Labor force growth

Participation rates, immigration flows, and the ability to keep older workers engaged (if they want to be) all shape

whether the workforce shrinks, stagnates, or expands.

If the U.S. “Japanifies,” What Would It Feel Like?

This isn’t just a macro theorypeople feel it in daily life. A Japan-style environment often comes with tradeoffs:

Savers get grumpy; borrowers get comfortable

Low interest rates can make it harder to earn returns on safe savings. That pushes households toward riskier assets

(stocks, real estate, private credit) just to keep upwhile borrowers enjoy cheaper financing.

Asset prices can stay elevated

When discount rates are low, the present value of future earnings rises. That can support high valuations for

equities and real estateeven if the underlying growth rate isn’t amazing.

“Zombie” risk becomes a thing

Easy credit can keep weak firms alive longer than they otherwise would. That may preserve jobs in the short run but

can weigh on productivity if capital stays stuck in low-performing uses.

Policy debates turn into a three-way tug-of-war

In a low-rate world, the central bank has less room to cut during recessions, fiscal policy becomes more central,

and political fights over debt and spending get louderbecause everyone wants the same dollar to solve five problems.

So… Is America Turning Japanese?

The most honest answer is: America has some Japan-like ingredients, but the recipe isn’t finished.

Yes, the U.S. is aging and carrying high (and rising) public debttwo big “Japanification” inputs. And yes, many

analysts still see long-run forces that keep interest rates from returning to the old high-rate era for good.

But the U.S. also has meaningful differences: immigration capacity, economic flexibility, and a track record of

innovation that can lift productivity.

The more useful question might be: Which parts of Japanification should the U.S. actively avoid?

Namely: letting productivity stagnate, allowing housing and childcare constraints to shrink the workforce,

and treating debt as “someone else’s future problem” rather than a present tradeoff.

Experience Appendix: of “Japanification” in Everyday Life

To make this idea feel real, picture how a Japan-style macro environment shows up in ordinary conversationsnot as

a dramatic crash, but as a slow change in what people expect.

Start with money in the bank. In a Japanified world, your friend doesn’t brag about a savings account interest rate

because it’s barely enough to buy a fancy coffee. That tiny yield becomes a quiet force pushing people to ask,

“If safe doesn’t pay, what’s the next safest thing?” So the family group chat fills up with words that sound like a

finance podcast: “short-term Treasuries,” “bond ladders,” “dividend funds,” “TIPS,” and “Is this ETF boring enough?”

The humor is that everyone is chasing “boring,” and somehow that becomes its own extreme sport.

Then there’s housing. When interest rates sit lower for longer, homeowners can get “locked in” emotionally to their

mortgage rate. Even if they want to move, they hesitate because the new loan would be pricier than the old oneso

mobility slows. People stay put, remodeling instead of relocating. Contractors get booked out. “Open house” culture

cools off, and “renovation culture” takes over. The economy still movesbut it shifts from constant churn to more

incremental upgrades.

In workplaces, the vibe changes too. Hiring becomes cautious, not panicky. Layoffs might remain low, but so does

rapid expansion. Job seekers notice fewer “wildly ambitious” postings and more roles that read like a careful

checklist: replace a retiree, maintain a system, keep the machine running. Companies may hold bigger cash piles,

waiting for certainty that never fully arrives. It’s not a recession mood; it’s a “let’s not get ahead of ourselves”

mood.

The aging piece is the most personal. More people spend time helping parents navigate healthcare, housing choices,

and long-term planning. Entire industries grow around this: home modifications, caregiving services, telehealth,

financial planning for retirement, and community support networks. You hear less about “starter homes” and more

about “aging in place.” That’s not automatically negativemany families value stabilitybut it changes how money is

spent and what politicians are asked to prioritize.

And finally, the national story gets more… managerial. Instead of a big cultural obsession with “the next boom,”

public debate revolves around how to keep living standards rising with fewer workers: boosting productivity, making

it easier to have kids if people want them, using immigration well, and keeping debt on a sustainable path. In other

words, the plot twist is that “Japanification” doesn’t feel like a single event. It feels like a decade where the

main character is compoundingquietly, relentlessly, and sometimes in the direction you least expect.