Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Brian Eno matters as a producer

- How to read this list

- Famous albums produced by Brian Eno (chronological highlights)

- 1975 Robert Calvert, Lucky Leif and the Longships (producer)

- 1977 Ultravox!, Ultravox! (studio assistance / co-credit variations)

- 1978 Devo, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! (producer)

- 1978 Talking Heads, More Songs About Buildings and Food (producer)

- 1979 Talking Heads, Fear of Music (producer, with Talking Heads)

- 1980 Talking Heads, Remain in Light (producer, with Talking Heads)

- 1984 U2, The Unforgettable Fire (co-producer, with Daniel Lanois)

- 1987 U2, The Joshua Tree (co-producer)

- 1991 U2, Achtung Baby (co-producer)

- 1993 U2, Zooropa (producer / production team)

- 1993 James, Laid (producer)

- 1994 James, Wah Wah (producer)

- 1994 Laurie Anderson, Bright Red (producer, with Anderson)

- 1999 James, Millionaires (producer)

- 2001 James, Pleased to Meet You (producer)

- 2008 Coldplay, Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends (producer)

- 2011 Coldplay, Mylo Xyloto (additional production / “enoxification”)

- Selected additional productions & special cases

- Famously not produced by Eno (but often assumed)

- What Eno brings to a session

- Extended list: 20+ notable albums with Eno in the producer chair

- Impact snapshots

- Frequently asked (and cleared up)

- Conclusion

- 500-word experience: what listening to “Eno-produced” really feels like

Short version: If a record sounds like the studio itself learned to breathe, there’s a good chance Brian Eno was in the room. From nervy late-’70s new wave to stadium-size reinventions, Eno’s producer credits map the evolution of modern pop and rocknudging bands toward risk, texture, and “happy accidents.”

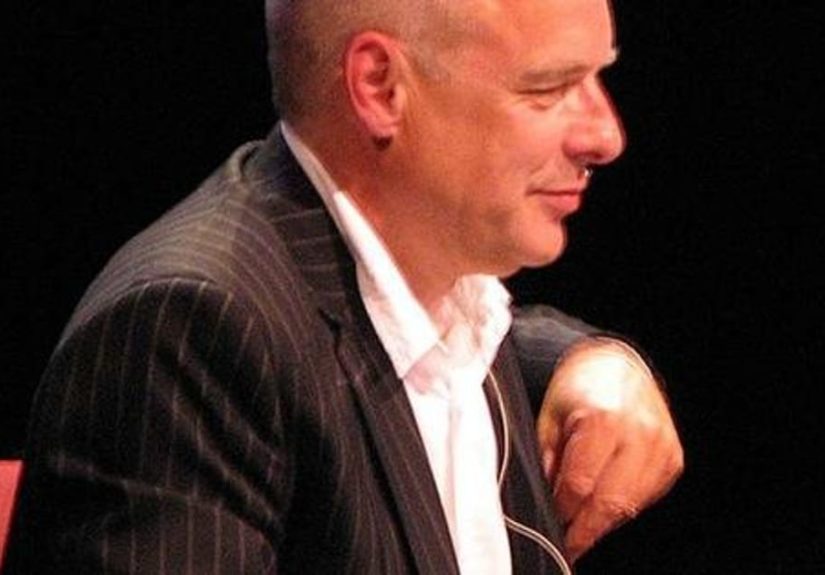

Why Brian Eno matters as a producer

Eno treats the studio as an instrumentpreferring systems, constraints, and lateral thinking (“Oblique Strategies”) over virtuoso solos. That approach helped shape landmark albums for Talking Heads, U2, Devo, Coldplay, James, and Laurie Anderson, among others, and turned experimentation into chart history.

How to read this list

Credits matter. Some albums list Eno as producer (primary), others as co-producer or additional production. We flag the role next to each album so you can separate “Eno at the console” from “Eno as creative catalyst.” Where the internet commonly misattributes producer credit (hello, Bowie’s Berlin era), we correct the record.

Famous albums produced by Brian Eno (chronological highlights)

1975 Robert Calvert, Lucky Leif and the Longships (producer)

Often cited as Eno’s first full producer credit, this concept album let him synthesize pop hooks with sound designthe seed of his later mainstream breakthroughs.

1977 Ultravox!, Ultravox! (studio assistance / co-credit variations)

Recorded with Steve Lillywhite, with Eno providing studio assistance and often receiving a co-credit in discographies. It’s a hinge between art-rock and synth-pop’s coming wave.

1978 Devo, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! (producer)

A jagged, herky-jerk debut polished to chrome by Enofriction we still dance to. His precision fortified Devo’s robotic funk without blunting the satire.

1978 Talking Heads, More Songs About Buildings and Food (producer)

Eno begins a three-album run with the band, swapping downtown minimalism for groove-centric architecture. A template for art-funk’s next decade.

1979 Talking Heads, Fear of Music (producer, with Talking Heads)

Industrial textures, West African rhythms, and anxiety as design principle. Eno’s “treatments” turn loft jams into shape-shifting songs.

1980 Talking Heads, Remain in Light (producer, with Talking Heads)

Polyrhythmic overdub ecstasy; the Brian-Eno-as-band-member vibe is palpable. Modern pop production still chases its layered density.

1984 U2, The Unforgettable Fire (co-producer, with Daniel Lanois)

U2 invite Eno to help escape post-punk austerity. Atmosphere, echo, and abstraction become part of the brand. It’s the start of a career-defining partnership with Daniel Lanois.

1987 U2, The Joshua Tree (co-producer)

Anthems with inner weather. Eno and Lanois broaden the sound while keeping songs front and centera balance that carried U2 onto history’s biggest stages.

1991 U2, Achtung Baby (co-producer)

The re-invention album: distortion, irony, Berlin grit. Eno’s periodic “erase the obvious” interventions helped the band pivot without losing their core.

1993 U2, Zooropa (producer / production team)

A collage of broadcast noise and late-night ideas stretched into a proper albumvery Eno.

1993 James, Laid (producer)

From Manchester bustle to intimate clarity. Eno pares the arrangements and lets Tim Booth’s vocals glow. Sister project Wah Wah captured the improvisatory side.

1994 James, Wah Wah (producer)

A bold “process record” born in the side-room while Laid was trackedjams, edits, and one-take mixing. A cult favorite that prefigures post-rock textures.

1994 Laurie Anderson, Bright Red (producer, with Anderson)

Elegiac art-pop with Eno’s floating architecture. Minimal elementsvoice, odd percussion, synth-aircarry surprising emotional weight.

1999 James, Millionaires (producer)

Sleek, radio-ready pop shaded by Eno’s harmonic depthproof he can do glossy without going shallow.

2001 James, Pleased to Meet You (producer)

Final chapter of the classic Eno-James run: muscular songs with atmospheric headroom.

2008 Coldplay, Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends (producer)

Coldplay’s grand redesign: shorter songs, bolder palettes, and that string-driven title track you still hear everywhere. Eno pushed “every song must sound different”and it worked.

2011 Coldplay, Mylo Xyloto (additional production / “enoxification”)

Less traditional producing, more creative direction. Credits actually say “enoxification”the Eno spark embedded in a maximalist pop canvas.

Selected additional productions & special cases

- Jane Siberry When I Was a Boy (1993): Eno produced select tracks; a luminous, ambient-inflected singer-songwriter statement.

- James Whiplash (1997): officially “occasional co-production and frequent interference”the most Eno credit ever.

Famously not produced by Eno (but often assumed)

David Bowie’s “Berlin trilogy”Low (1977), “Heroes” (1977), Lodger (1979)owes massive sonic DNA to Eno, but the producer credit belongs to Tony Visconti; Eno is a collaborator, co-writer, and sonic architect. It’s a crucial distinction that still honors his role.

What Eno brings to a session

- Systems over solos. He’ll change the rules (new tunings, odd mic placement, “no cymbals today”) to change the results.

- Erase the obvious. Heard on U2’s Achtung Baby: remove the parts that sound like the band’s clichés, keep the electricity.

- Texture as hook. Think Remain in Light or Viva la Vida: rhythm beds and timbres do as much work as melodies.

Extended list: 20+ notable albums with Eno in the producer chair

- Robert Calvert Lucky Leif and the Longships (1975) producer.

- Ultravox! Ultravox! (1977) studio assistance/co-credit context.

- Devo Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! (1978) producer.

- Talking Heads More Songs About Buildings and Food (1978) producer.

- Talking Heads Fear of Music (1979) producer (with band).

- Talking Heads Remain in Light (1980) producer (with band).

- U2 The Unforgettable Fire (1984) co-producer.

- U2 The Joshua Tree (1987) co-producer.

- U2 Achtung Baby (1991) co-producer.

- U2 Zooropa (1993) producer/production team.

- James Laid (1993) producer.

- James Wah Wah (1994) producer.

- Laurie Anderson Bright Red (1994) producer (with Anderson).

- Jane Siberry When I Was a Boy (1993) produced select tracks.

- James Millionaires (1999) producer.

- James Pleased to Meet You (2001) producer.

- Coldplay Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends (2008) producer.

- U2 No Line on the Horizon (2009) producer (with Lanois et al.).

- Coldplay Mylo Xyloto (2011) additional production/“enoxification.”

Impact snapshots

Talking Heads: Eno’s trilogy (’78–’80) converts post-punk nervousness into polyrhythmic joy, laying groundwork for dance-punk and indie-funk.

U2: From cathedral echoes (Unforgettable Fire) to reinvention theater (Achtung Baby), Eno and Lanois help U2 transcend genre while remaining unmistakably U2.

Coldplay: Viva la Vida tightens songcraft and expands color; Eno coaxes variation and risk, yielding the band’s biggest global moment.

Devo & Ultravox!: Early new-wave modernism gets high-contrast clarity; the synth future arrives sounding suspiciously fun.

James & Laurie Anderson: Two long relationshipsone rock, one art-popshow Eno’s range from intimate confessional to conceptual minimalism.

Frequently asked (and cleared up)

- Did Eno “produce” Bowie’s Berlin albums? No; Tony Visconti produced. Eno collaborated deeply, but the title “producer” is Visconti’s.

- What’s “enoxification” on Coldplay credits? Eno’s term for creative direction and additional productionsonic seasoning plus process tweaks. :contentReference[oaicite:51]{index=51}

Conclusion

Great producers don’t just capture performances; they design conditions where inspired performances become inevitable. Across five decades, Brian Eno has done exactly thatquietly changing how big bands think, write, and record, and making the experimental feel inevitable.

SEO wrap-up

sapo: From art-rock laboratories to stadium anthems, Brian Eno’s producer credits map modern music’s boldest turns. This in-depth guide traces the essential albums he produced (or co-produced), what he actually did on each record, why those choices mattered, and how his studio-as-instrument philosophy turned risks into classics. If you’ve ever wondered why Remain in Light grooves like circuitry, how U2 kept reinventing itself, or what “enoxification” means on a Coldplay LP, this is the field guidewith clear credits and contextto understanding Eno’s long shadow over pop and rock.

500-word experience: what listening to “Eno-produced” really feels like

Spend a weekend living with these records and a pattern emerges. First, the drum space: whether it’s Chris Frantz’s uncluttered pocket on Fear of Music or Larry Mullen Jr.’s echo-shaped toms on The Unforgettable Fire, the kit sits in a room you can almost see. Eno tends to clear cymbal wash, let snares breathe, and place percussion like furnitureso the groove reads as architecture, not clutter. Then there’s the foreground texture that behaves like a hook: Talking Heads’ treated guitars, The Edge’s smeared harmonics, Coldplay’s string loops on “Viva la Vida.” Melody still leads, but timbre does equal work. On Laid, for example, James sound both intimate and widescreen because the textures are edited to leave emotional air around the vocal.

Another sensation is the feeling of process audible. Eno loves constraints because they create surprise. You can hear it when bands jam long past the “song” and then a smaller, stranger moment becomes the record: Wah Wah is full of these one-take edits; Zooropa feels like late-night TV captured by a band. Even on the pop-polished Viva la Vida, you can sense the ruleeach song must sound differentnudging Coldplay away from default choices. The thrill isn’t just “new sound,” it’s new behavior from familiar artists.

There’s also a producer’s humility that reads as boldness. Eno often co-produces with Daniel Lanois or steps back into “additional production,” but the fingerprints are consistent: get rid of the obvious part; keep the part that changes how we listen. That’s why U2 could move from chiming hymns to industrial swagger without losing themselvesbecause the method foregrounded the song, not the trick. It’s also why Laurie Anderson’s Bright Red projects so much feeling from so few ingredients; subtraction becomes an amplifier.

Perhaps the most useful takeawaywhether you’re a musician, podcaster, or weekend playlist tinkereris Eno’s bias for systems that generate. Make three rules before you start (no cymbals; vocals below middle C; one sound per bar that can’t repeat) and let those rules write half the piece. Record for too long, then edit like a film. Put the weirdest thing in the middle and make the song earn it. If you’re mixing, treat ambience as composition, not decoration: choose one space per song and stage the instruments inside it.

Finally, listen across time. Start with Devo’s debut, jump to Talking Heads’ Remain in Light, land on U2’s Achtung Baby, then Coldplay’s Viva la Vida. The path isn’t just “Eno did all of these”; it’s a map of how risk moves from the margins to the center of pop. That’s the Eno effect: a gentle shove toward the unknown that somehow feels, years later, like the only logical way those songs could ever have sounded. :contentReference[oaicite:52]{index=52}