Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First, What Exactly Is “Congestive” Heart Failure?

- Now the Diabetes Part: Why Blood Sugar Isn’t the Whole Story

- How Diabetes Raises the Risk of Heart Failure

- How Heart Failure Can Make Diabetes Harder to Manage

- Warning Signs: When “Normal Diabetes Tired” Isn’t the Whole Story

- How Clinicians Evaluate the Diabetes–Heart Failure Connection

- Treatment: Protecting the Heart Without Wrecking Blood Sugar

- Prevention: If You Have Diabetes, How Do You Lower Heart Failure Risk?

- Putting It All Together

- Real-World Experiences: What Living With Both Can Feel Like (About )

If you ever wanted proof that the human body loves teamwork, meet this not-so-cute duo: diabetes and

congestive heart failure (often just called “heart failure” or “CHF”). They show up separately all the time.

But together? They’re like two coworkers who keep “circling back” and somehow make everything more complicated.

The good news: yes, there’s a real, well-studied connectionand understanding it can help people lower risk,

spot warning signs earlier, and make treatment choices that protect both blood sugar and the heart.

Let’s break it down in plain American English, with just enough humor to keep the medical vocabulary from

putting anyone into a nap they didn’t schedule.

First, What Exactly Is “Congestive” Heart Failure?

Heart failure does not mean the heart suddenly “stops.” It means the heart can’t pump blood as well as

the body needs. When pumping gets weak or the heart becomes stiff and doesn’t fill properly, fluid can back up

into the lungs, legs, and bellyhence the word congestive.

Clinicians often describe heart failure by the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), or how much blood

the left ventricle pumps out with each beat:

- HFrEF (reduced EF): the squeeze is weaker.

- HFpEF (preserved EF): the squeeze may be okay, but the heart is stiff and doesn’t fill well.

- HFmrEF (mildly reduced EF): somewhere in between.

Now the Diabetes Part: Why Blood Sugar Isn’t the Whole Story

Diabetesespecially type 2affects far more than glucose numbers. Over time, higher blood sugar can damage

blood vessels and nerves. Diabetes also commonly travels with high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol,

kidney disease, inflammation, and extra weightall of which can strain the heart.

So when people ask, “Is there a connection between congestive heart failure and diabetes?” the honest answer is:

Yesand it’s not just one connection. It’s a whole web.

How Diabetes Raises the Risk of Heart Failure

1) Diabetes accelerates artery trouble (and the heart pays the rent)

Diabetes increases the risk of atherosclerosisplaque buildup in arteries. If coronary arteries narrow, the heart

muscle can get less oxygen. That can lead to heart attacks, scarring, and eventually weaker pumping ability.

Even without a big dramatic heart attack moment, years of reduced blood flow can slowly wear the heart down.

2) “Diabetic cardiomyopathy” is a real thing

Here’s the part many people don’t hear about until they’re already deep into cardiology appointments:

diabetes can affect the heart muscle directly, even without blocked arteries or uncontrolled blood pressure.

This is often called diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Researchers describe multiple ways this can happen:

-

Metabolic stress: the diabetic heart may rely more on fatty acids and less on efficient fuel use,

which can be harder on heart cells over time. -

Inflammation and oxidative stress: chronic low-grade inflammation can promote scarring (fibrosis)

and stiffness. -

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): sugar-related “sticky” compounds that can make tissues

less flexible. - Microvascular dysfunction: tiny blood vessels that feed the heart muscle may not work as well.

The practical result is often a heart that becomes stiffer (a setup for HFpEF) or gradually weaker (a setup for HFrEF).

3) The usual suspects show up together

Diabetes frequently overlaps with other heart failure risk factors:

high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, obesity, sleep apnea, and high triglycerides.

It’s less like “one villain” and more like a whole cast.

How Heart Failure Can Make Diabetes Harder to Manage

The relationship goes both ways. Once heart failure develops, diabetes management often becomes trickier:

- Less activity: fatigue and shortness of breath can reduce movement, which can raise insulin resistance.

-

Kidney changes: heart failure can reduce kidney perfusion; the kidneys influence glucose control and

also affect how diabetes medications are processed. -

Fluid shifts and appetite changes: swelling, nausea, or early fullness (from abdominal congestion)

can make eating patterns unpredictable. -

Medication juggling: diuretics may affect electrolytes; some diabetes drugs are not ideal in certain

stages of heart failure.

In real life, this often means the care plan needs tighter teamwork between primary care, endocrinology,

and cardiologybecause the body isn’t keeping these systems in separate folders.

Warning Signs: When “Normal Diabetes Tired” Isn’t the Whole Story

Lots of things can cause fatigue. But heart failure has patterns that matterespecially in someone with diabetes.

Common signs include:

- Shortness of breath during routine activity or when lying flat

- Swelling in feet, ankles, legs, or belly

- Rapid weight gain over a few days (often from fluid, not cupcakes)

- Unusual fatigue or reduced exercise tolerance

- Waking up breathless or needing extra pillows to sleep

If these show upespecially suddenlyit’s worth getting evaluated. Early treatment can prevent a small problem

from turning into an emergency room sequel.

How Clinicians Evaluate the Diabetes–Heart Failure Connection

Diagnosis usually combines symptoms, a physical exam, and testing. Common tools include:

- Blood tests (including natriuretic peptides like BNP/NT-proBNP in many cases)

- Echocardiogram to assess ejection fraction and heart structure

- EKG for rhythm issues

- Kidney function tests and electrolytes (especially when diuretics or certain diabetes meds are used)

- A1C and glucose patterns to guide diabetes strategy

Many professional guidelines also emphasize identifying people “at risk” for heart failurewhere diabetes is a big flag

so prevention can start before symptoms appear.

Treatment: Protecting the Heart Without Wrecking Blood Sugar

The foundation: lifestyle that works for both conditions

The best lifestyle advice is boring because it works:

a heart-healthy eating pattern, regular movement as tolerated, smoking cessation, good sleep, and stress management.

With heart failure, sodium and fluid guidance may be individualized. With diabetes, carbohydrate quality and portions

matter. The overlap is actually pretty friendly:

- Focus on vegetables, beans, nuts, whole grains, and lean proteins.

- Go easy on ultra-processed foods (they’re often sodium + sugar + regret).

- Build activity slowlywalking counts, and consistency beats intensity.

- Track blood pressure and weight trends if recommended.

Heart failure “core” meds (and why they matter even with diabetes)

For many people with HFrEF, modern guideline-directed therapy commonly includes several medication classes

that improve symptoms and outcomes. Depending on the situation, clinicians may use:

- ARNI (or ACE inhibitor/ARB in some cases)

- Evidence-based beta blockers

- Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs)

- SGLT2 inhibitors

- Diuretics for fluid relief (these help symptoms, even if they’re not the “main character” for long-term outcomes)

Not every medication fits every person. But the overall goal is consistent: reduce fluid overload, decrease heart strain,

and prevent hospitalization and progression.

SGLT2 inhibitors: the “two birds, one prescription” moment

One of the biggest shifts in recent years is that a diabetes drug classSGLT2 inhibitorsbecame a

major heart failure therapy. Large clinical trials showed meaningful reductions in heart failure worsening and

hospitalizations, and benefits were seen even in many patients without diabetes.

In everyday terms, SGLT2 inhibitors can:

- Lower glucose modestly (in type 2 diabetes)

- Promote mild fluid and sodium loss through the kidneys

- Support kidney protection in many patients

- Reduce heart failure events in multiple heart failure categories

Like any medication, they’re not for everyone. Clinicians typically review kidney function, infection risk,

dehydration risk, and rare complications (like ketoacidosis in specific situations) before starting.

Diabetes medications that deserve extra caution in heart failure

Diabetes treatment should be individualized, but a few notes commonly come up when heart failure is in the picture:

-

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) (like pioglitazone/rosiglitazone) can cause fluid retention and may worsen

or precipitate heart failure in some patientsso clinicians often avoid them in symptomatic heart failure. -

Some DPP-4 inhibitors have labeling warnings about heart failure risk (notably saxagliptin and alogliptin),

so providers may choose alternatives if someone has heart failure risk factors. -

Insulin and sulfonylureas can be appropriate but require careful monitoring to avoid hypoglycemia,

especially if appetite fluctuates or kidney function changes.

The point isn’t that diabetes meds are “good” or “bad.” It’s that heart failure changes the chessboard, and your

care team may pick a different opening move.

Prevention: If You Have Diabetes, How Do You Lower Heart Failure Risk?

You can’t control every risk factor (genetics has entered the chat), but you can influence the big ones:

- Keep blood pressure controlled (it’s one of the strongest drivers of heart failure risk).

- Manage cholesterol and address smoking if relevant.

- Protect the kidneyskidney and heart outcomes are closely linked.

- Address sleep apnea if symptoms suggest it (snoring + daytime sleepiness is worth mentioning).

- Ask about cardioprotective diabetes medications if you have risk factors.

Prevention is not a single magic trick. It’s a bunch of small, boring, repeatable choices that add uplike compound

interest, but for your heart.

Putting It All Together

Yesthere is a strong connection between congestive heart failure and diabetes. Diabetes can raise heart failure risk

through blood vessel disease, shared risk factors (like hypertension and kidney disease), and direct effects on the heart

muscle itself. Heart failure can then complicate diabetes management through fatigue, reduced activity, kidney changes,

and medication complexity.

The most hopeful part of this story is that modern care is increasingly designed for the overlap. Many of the same

strategieshealthy eating, movement, blood pressure control, and certain medication choicessupport both conditions.

If you or someone you care about lives with diabetes, learning heart failure warning signs and discussing risk-reducing

treatment options with a clinician can make a real difference.

Medical note: This article is for general education and isn’t a substitute for individualized medical advice.

If you suspect heart failure symptoms or have diabetes with new swelling or breathlessness, contact a healthcare professional.

Real-World Experiences: What Living With Both Can Feel Like (About )

People who live with both diabetes and heart failure often describe the experience as less like “one illness”

and more like managing a busy group chat where everyone talks at once. The heart failure side might show up as

breathlessness on stairs that used to be easy, or that frustrating kind of fatigue where you’re tired before the day

even starts. The diabetes side keeps humming in the background: meal planning, glucose checks (or CGM alarms),

and trying to keep numbers steady while life insists on being… life.

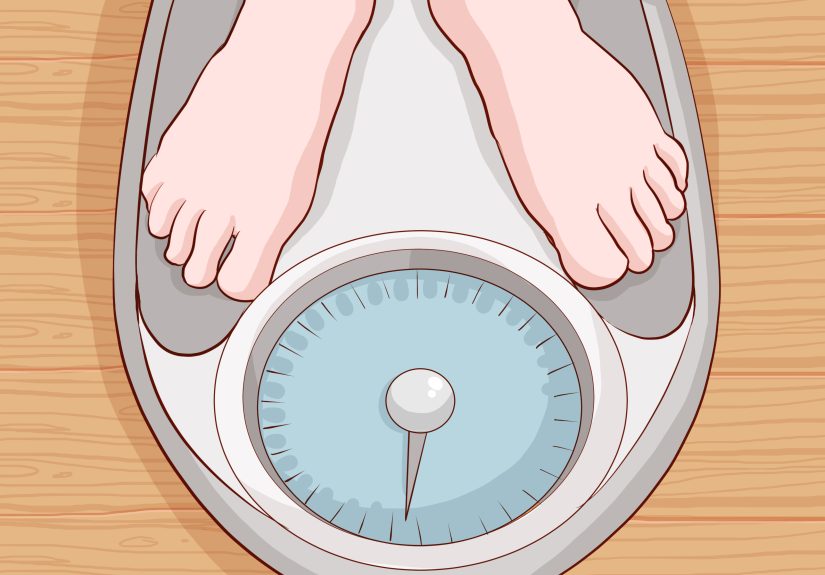

One common experience is learning the difference between weight and fluid. People may notice a few pounds

appear quicklytoo quickly to be body fatand the pattern becomes a clue. Shoes feel tighter. Socks leave deeper marks.

A ring that used to slide off starts negotiating. In many care plans, tracking weight trends becomes a practical early-warning

system, not a vanity project. The scale becomes less “judge and jury” and more “weather report.”

Another theme is food label detective work. Diabetes pushes people to watch carbohydrate quality and timing,

while heart failure may require paying closer attention to sodium. That can feel like grocery shopping on “hard mode,” especially

with processed foods. Many people end up building a rotation of “safe meals”simple breakfasts, reliable lunches, and dinners that

don’t taste like punishment. Over time, confidence grows: you learn which soups are secretly salt bombs, how to season with herbs,

and why restaurant meals can cause next-day swelling even if blood sugar behaved.

Medication routines can also feel like a part-time job. A diuretic may mean planning around bathrooms (yes, really).

Some people joke that their morning schedule is basically: pills, water, bathroom, repeat. Meanwhile, diabetes medications may need

adjustment if appetite changes or kidney function shifts. It’s not unusual for patients to report that what helps the heart

(like fluid reduction) can temporarily make them feel “off” until the body finds a new normal. The best experiences tend to happen

when people feel comfortable reporting side effects earlybefore they snowball.

Emotionally, the overlap can be heavy. People describe feeling anxious when symptoms flare: “Is this just a bad day, or is it something bigger?”

Support helpswhether that’s a family member who walks with you, a friend who shares low-sodium recipes, or a clinician who explains the plan

in human language. Many also find that small wins matter: walking five more minutes than last week, waking up less swollen,

seeing steadier glucose patterns, or staying out of the hospital. In the end, living well with both conditions usually isn’t about perfection.

It’s about consistency, communication, and building routines that make your heart and blood sugar a little easier to live withone ordinary day

at a time.