Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First: What “Getting Infected” Actually Means

- Stage 1: The Upper Airway Battle (Nose and Throat)

- Stage 2: The Immune System Goes From “Bouncer” to “SWAT Team”

- Stage 3: The Lungs (When It Moves From “Annoying” to “Serious”)

- Stage 4: Blood Vessels and Clotting (The “Plumbing” Problem)

- Stage 5: The Heart (Inflammation Has No Respect for Boundaries)

- Stage 6: The Brain and Nervous System (Yes, Brain Fog Is Real)

- Stage 7: The Gut, Liver, and Kidneys (Because the Body Is One Big Group Project)

- Why Some People Have No Symptoms (Or Barely Any)

- Recovery: How the Body Cleans Up After the Party Guest Leaves

- Long COVID: When Symptoms Stick Around Longer Than Anyone Invited Them To

- When to Take It Seriously (Without Panic)

- Putting It All Together: The Big Picture

- of Real-World “This Is What It Can Feel Like” Experiences

- SEO Tags

Imagine your body is a well-run city. Then a tiny, uninvited guest shows upSARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19).

Most of the time, your immune system escorts it out with minimal drama. Other times, the “security team” overreacts, traffic lights

break, and suddenly the whole city is dealing with congestion, detours, and a lot of exhausted citizens.

This article breaks down what’s happening inside the bodystep by step, system by systemwhen someone gets infected. It’s not meant to

replace medical advice. It’s meant to make the biology feel less like a pop quiz and more like a movie you can actually follow.

First: What “Getting Infected” Actually Means

Infection starts when enough virus particles reach vulnerable tissuemost often the nose, throat, and upper airways. The virus uses a

“key” on its surface (spike protein) to attach to receptors on human cells (ACE2 is a well-known one). Once inside a cell, the virus

hijacks the cell’s machinery to make more copies of itself. That replication phase is why you can feel fine at first but still be

contagious: the virus is quietly multiplying before the immune system fully flips the alarm switch.

Incubation: the quiet part before the loud part

Symptoms commonly begin a few days after exposure, but timing varies. During this window, the virus may be building a foothold in the

upper airway. Your body is already respondingjust not loudly enough for you to notice yet. Think: silent security cameras, not sirens.

Stage 1: The Upper Airway Battle (Nose and Throat)

For many people, COVID-19 stays mostly in the “front of house” of the respiratory tract. That’s why early symptoms often resemble a cold

or flu: sore throat, congestion, runny nose, cough, mild fever, and general “I would like to be a blanket burrito” fatigue.

Why do you feel so wiped out?

Fatigue isn’t lazinessit’s biology. When immune cells detect viral activity, they release signaling proteins (cytokines) that coordinate

defense. Those same signals can also make you sleepy, achy, and foggy. Your body is diverting energy toward fighting and repair, and it

encourages you to rest (which, inconveniently, is exactly what you want to do anyway).

What about loss of taste or smell?

Earlier in the pandemic, sudden loss of smell/taste was a standout symptom. It can still happen, but it’s not as universal as people

remember. When it does occur, it’s thought to involve inflammation and disruption in the smell pathway, rather than the virus simply

“turning off” taste buds like a light switch.

Stage 2: The Immune System Goes From “Bouncer” to “SWAT Team”

Your immune response has two big phases:

- Innate immunity: fast, general, and a little chaotic. It tries to slow viral replication immediately.

- Adaptive immunity: slower but precise. It builds antibodies and T cells targeted to the virus.

In a smooth recovery, these phases coordinate like a good relay race: early defenders buy time, then targeted defenders finish the job,

and the inflammation settles down.

When things get complicated

Severe COVID-19 tends to involve a combination of high viral activity (especially deeper in the lungs) and an immune response that becomes

overly inflammatory or poorly timed. That inflammation can affect blood vessels and organs beyond the lungs. This is one reason COVID-19

isn’t “just a respiratory infection” for everyoneyour immune system and circulatory system can get pulled into the conflict.

Stage 3: The Lungs (When It Moves From “Annoying” to “Serious”)

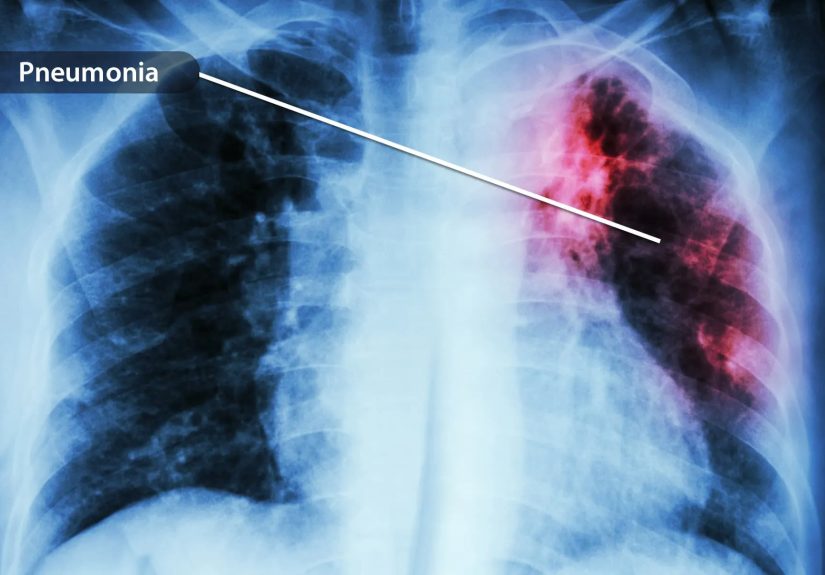

If the virus reaches the lower respiratory tract, it can inflame delicate lung tissue where oxygen moves into the blood. Mild cases may

cause a persistent cough and some shortness of breath. More serious cases can involve pneumonia and impaired oxygen exchange.

Why oxygen levels can drop

Healthy air sacs in the lungs are like tiny, efficient exchange booths: oxygen in, carbon dioxide out. Inflammation can thicken the

barrier or fill spaces with fluid and immune debris. The result is less efficient oxygen transferlike trying to breathe through a scarf

that keeps getting wetter.

Example: A healthy, vaccinated teenager might feel like they have a rough cold for several days and recover with rest and

hydration. A much older adult with chronic health conditions may be more likely to develop significant breathing problems if infection

progresses into the lungs.

Stage 4: Blood Vessels and Clotting (The “Plumbing” Problem)

One of the most important discoveries of the pandemic was that COVID-19 can affect the lining of blood vessels (the endothelium) and shift

the body toward a more “clot-friendly” state, especially in severe illness. Inflammation and endothelial stress can make clotting more

likely, particularly in hospitalized patients and those with additional risk factors.

Why that matters

Blood vessels are your body’s delivery network. If inflammation makes that network less smoothmore sticky, more reactivecirculation can

be disrupted. This helps explain why COVID-19 has been associated with complications involving the heart, brain, and lungs in more serious

cases.

Important note: most people with mild disease do not experience dangerous clotting. Risk rises with severe disease and certain underlying

conditions, which is why clinicians pay close attention to it in higher-risk situations.

Stage 5: The Heart (Inflammation Has No Respect for Boundaries)

The heart can be affected directly or indirectly through inflammation, oxygen strain, and vascular effects. Some people experience chest

discomfort, palpitations, or a racing heartbeat during or after infection. In more serious situations, inflammation can contribute to

rhythm issues or heart muscle stress.

What “post-COVID heart symptoms” can look like

- Feeling your heart “skip” or race

- Shortness of breath with activity that used to be easy

- Fatigue that feels disproportionate to the effort

These symptoms can have many causes, and they deserve medical evaluationespecially if they’re new, persistent, or severe.

Stage 6: The Brain and Nervous System (Yes, Brain Fog Is Real)

COVID-19 can affect the nervous system in multiple waysthrough inflammation, disrupted sleep, reduced activity during illness, stress, and

in some cases direct or indirect effects on the brain’s support systems (like blood vessels). Many people report headaches, dizziness, and

difficulty concentrating during the acute illness.

Brain fog, explained in human language

“Brain fog” isn’t a single symptom. It’s a cluster: slower thinking, trouble focusing, forgetfulness, and feeling mentally “buffering.”

In the short term, this can be part of the body-wide inflammatory response. For some, it can linger longer (more on that below).

Stage 7: The Gut, Liver, and Kidneys (Because the Body Is One Big Group Project)

ACE2 receptors and immune activity aren’t limited to the lungs. COVID-19 may also involve the digestive tract, leading to nausea,

vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort in some people. The liver can show signs of stress during infection (often noted in lab

testing in clinical settings). Kidneys may also be affected in severe illness, especially when dehydration, inflammation, and low oxygen

levels stack the odds against them.

For most people with mild cases, these issues are temporary. In severe casesparticularly among those already medically vulnerableorgan

stress can become a major part of the illness picture.

Why Some People Have No Symptoms (Or Barely Any)

Asymptomatic infection is real. It may happen when the immune system controls viral replication quickly, or when infection stays largely in

the upper airway without provoking a strong inflammatory response. Vaccination and prior infection can also shift the odds toward milder

disease by preparing the immune system to respond faster and more effectively.

But “no symptoms” doesn’t always mean “no effects”

Most asymptomatic people do fine. Still, researchers have explored whether subtle inflammation or temporary changes can occur even without

obvious symptoms. The practical takeaway: symptoms are useful clues, but they’re not the whole storywhich is why testing and public health

guidance mattered so much.

Recovery: How the Body Cleans Up After the Party Guest Leaves

Clearing the virus is only part of the job. Your body then needs to:

- Calm inflammation

- Repair irritated tissues

- Rebalance sleep, appetite, and hydration

- Rebuild stamina (especially after bed rest)

Many people feel noticeably better within days to a couple of weeks. Others recover more slowly, especially after severe disease.

Vaccination, underlying conditions, viral dose at exposure, and individual immune differences all shape the recovery curve.

Long COVID: When Symptoms Stick Around Longer Than Anyone Invited Them To

“Long COVID” (also called post-COVID conditions or post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection) describes a wide range of symptoms that

persist or appear after the acute infection. Definitions vary, but many clinical descriptions focus on symptoms lasting for months and

affecting daily function.

Common long COVID symptom clusters

- Fatigue and post-exertional symptom worsening (feeling “crashed” after activity)

- Shortness of breath or reduced exercise tolerance

- Brain fog, memory issues, headaches

- Heart rate and blood pressure changes (including dysautonomia-like symptoms in some)

- Sleep problems and mood changes

- Lingering taste/smell disturbances

Why might long COVID happen?

Researchers are studying multiple, possibly overlapping mechanisms. These include immune system dysregulation, lingering inflammation,

effects on blood vessels, and the possibility of persistent viral fragments or reservoirs in some tissues. Not every case looks the same,

and not every hypothesis fits every patientwhich is why long COVID is best thought of as a syndrome (a pattern) rather than one single,

tidy disease.

When to Take It Seriously (Without Panic)

Most infections are mild, but some symptoms deserve urgent attentionespecially significant trouble breathing, severe chest pain/pressure,

confusion, or symptoms that rapidly worsen. If someone is in immediate danger, seek emergency care right away.

If symptoms linger for weeks or monthsespecially fatigue, breathing issues, chest discomfort, or cognitive changesit’s reasonable to talk

with a healthcare professional. COVID-19 can overlap with other conditions, and getting the right evaluation matters.

Putting It All Together: The Big Picture

COVID-19 is a respiratory infection that can become a whole-body event. In many people, it’s brief and manageable. In others, it triggers

widespread inflammation that affects blood vessels, the lungs, and sometimes multiple organs. The difference often comes down to how fast

the immune system recognizes the virus, how well it controls replication, and whether inflammation stays proportionateor turns into a

runaway group chat nobody can mute.

The good news: immunity from vaccination and prior infections has helped reduce the risk of severe outcomes for many people, and medical

care has improved since the earliest days of the pandemic. The honest news: COVID-19 is still capable of knocking the wind out of youboth

literally and metaphoricallyand some people do deal with longer recoveries.

of Real-World “This Is What It Can Feel Like” Experiences

To make this topic feel less abstract, here’s a composite of common experiences people have described during and after infection. This

isn’t one person’s story and it isn’t a medical checklistit’s a “pattern collage” built from widely reported symptom timelines.

The early days: “Is this allergies… or am I doomed?”

A lot of people describe COVID’s beginning as annoyingly ambiguous. Day one might be a scratchy throat and a little congestionnothing that

screams “global pandemic,” more like “I slept with a fan on.” By day two, fatigue often arrives like an uninvited houseguest who eats all

your snacks and refuses to leave. Some people feel feverish and achy, like their muscles are protesting with tiny picket signs.

The mid-phase: the body-wide reminder that your immune system is busy

Around days three to five, many people report peak symptoms: a persistent cough, headache, and the kind of tiredness that makes brushing

your teeth feel like an extreme sport. If you’ve ever had the flu, the vibe can be similarexcept COVID sometimes adds its own odd twists.

Some people notice a sudden change in smell or taste (coffee tastes like warm sadness, or everything tastes like “texture” instead of

flavor). Others experience stomach upset and lose their appetitenot because they’re being picky, but because the body is treating food as

a low priority while it runs an internal emergency meeting.

The turning point: “I think I’m better… wait, am I?”

Many mild cases start improving after about a week. Fever breaks, congestion eases, and energy begins creeping back. But it’s common to

feel “better but not normal.” People describe it as being at 70% battery and watching the charger work slowly. A short walk might feel

surprisingly tiring. A normal day of school or work can feel like doing it with a backpack full of bricks you didn’t agree to carry.

Weeks later: the slow rebuild

For lots of people, the lingering part is a cough that hangs around, or stamina that returns in small installments. Sleep can be weird for

a whileeither too much or not enough. And then there are those who experience long COVID patterns: fatigue that flares after activity,

brain fog that makes reading a paragraph feel like running a marathon, or a heartbeat that seems overly enthusiastic about minor effort.

What many people find most frustrating isn’t painit’s unpredictability. One day feels normal, the next day feels like the body hit a

“please reboot” button.

The shared thread in these experiences is that COVID is often less about one symptom and more about a whole-body state. It’s the immune

system, the nervous system, the lungs, and the recovery process all negotiating at oncesometimes smoothly, sometimes loudly.