Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What a Bull Market Actually Feels Like (Spoiler: Not Like a Spa Day)

- Why Bull Markets Still Feel Hard

- Why Your Brain Makes “Up” Feel Like “Danger”

- A Bull Market Survival Kit (No Cape Required)

- Concrete Examples: What “Staying Invested” Looks Like

- How to Prepare for the End of a Bull Market (Without Pretending You Can Predict It)

- Conclusion: Bull Markets Aren’t a Free LunchThey’re a Long Recipe

- Real-Life Bull Market Lessons ( of Experience)

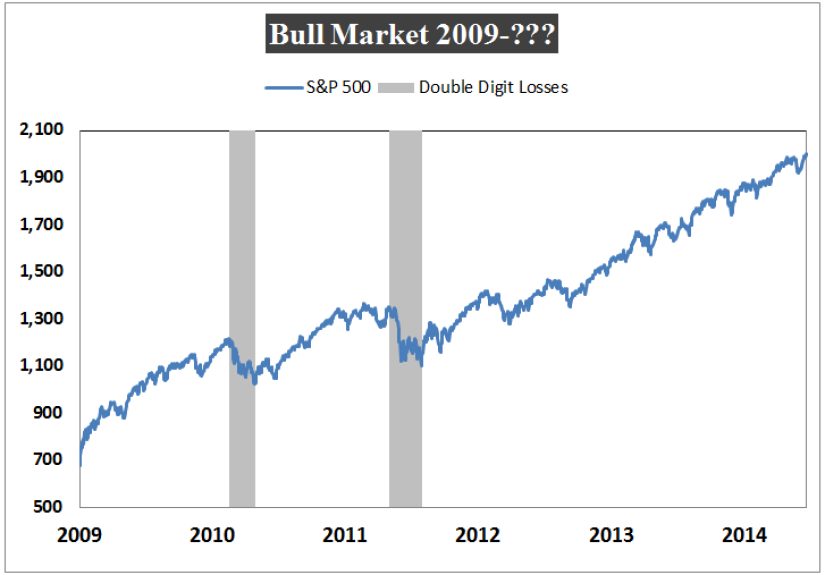

A bull market is supposed to feel like a victory lap. Confetti. High-fives. Your portfolio doing that delightful “up-and-to-the-right” thing.

And yet… somehow it still feels like riding a mechanical bull that’s been caffeinated.

That’s the dirty secret of investing: markets can be going up overall while your emotions are going down the stairs two at a time.

The chart looks smooth in hindsight, but living through it feels like checking the oven every 30 seconds and wondering if you’re somehow baking regret.

What a Bull Market Actually Feels Like (Spoiler: Not Like a Spa Day)

In everyday investing talk, “bull market” usually means stocks are broadly trending higher over time. But “trending higher” does not mean “moving higher every day,”

and it definitely doesn’t mean “your brain will chill out and let you enjoy it.”

Bull markets include sudden dips, scary headlines, and moments when your group chat turns into a panel of amateur macroeconomists.

They also include a constant parade of new all-time highswhich sounds great until your brain translates it as:

“So… is this the top?”

Why Bull Markets Still Feel Hard

1) Volatility is the cover charge

Markets don’t hand out long-term returns for free. The “price” is volatilitythe gut-punch days, the 2% drops that feel like the beginning of the end,

and the occasional correction that makes you swear you’re “never looking at the app again” (until tomorrow morning).

One of the most useful reality checks: big intra-year pullbacks are common even when the year ends up positive.

In other words, the market can spend part of the year trying to emotionally evict you, then finish the year like nothing happened.

That’s not a bug. That’s the business model.

2) All-time highs are normal… but they sound suspicious

“All-time high” sounds like “peak,” as if the market has reached the top of Mount Profit and must now tumble back down.

But historically, all-time highs often come in clusters. When markets are strong, they tend to keep making new highs.

The emotional trap is that buying or staying invested at record levels can feel like ordering a $19 salad:

you’re not sure it’s worth it, and you’re certain you’ll regret it if it disappoints.

Meanwhile, time keeps passing, and the market keeps doing its thing.

3) Leadership changes, and that can be unsettling

Bull markets don’t lift every stock equally. Leadership rotates. Some years, a handful of mega-cap names carry the index.

Other years, boring sectors and “who even talks about that industry?” stocks quietly do the heavy lifting.

That rotation can make investors feel like they’re always late: you own yesterday’s winners, watch them cool off,

and start eyeballing whatever’s currently trending. Congratulationsyou’ve discovered performance chasing, one of the most expensive hobbies on Earth.

4) The best days often hide near the worst days

Here’s the cruel joke: if you panic-sell after a sharp drop, you’re more likely to miss the rebound.

The market’s strongest single-day moves often happen around periods of stress, uncertainty, and “maybe I should go to cash forever” vibes.

That’s why so many long-term studies show the same pattern: investors who try to dodge volatility often end up dodging the recovery, too.

And recovery is where compounding earns its keep.

5) The “behavior gap” is real

Markets don’t just test portfolios; they test people. Many investors earn less than the funds or markets they invest in, largely because of timing decisions

buying after a run-up, selling after a drop, then waiting for a “clear sign” that it’s safe to return (spoiler: markets rarely provide that sign).

The gap isn’t usually caused by one dramatic mistake. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts: tiny, emotional decisions made during noisy moments.

The enemy isn’t the bear market. It’s the human urge to “do something” at exactly the wrong time.

Why Your Brain Makes “Up” Feel Like “Danger”

Loss aversion: drops feel bigger than gains

Behavioral finance has a very unromantic message: losing money feels worse than gaining the same amount feels good.

So even if the market is up over the year, the down days can dominate your memory and mood.

Your brain is basically a negativity-bias machine with a refresh button.

Myopic risk: checking too often amplifies fear

The more frequently you check, the more volatility you experience. A long-term investor who checks daily is essentially binge-watching short-term randomness.

It’s like judging a movie by pausing every 30 seconds and rating the lighting.

Regret is a powerful (and terrible) financial advisor

Investors don’t just fear lossesthey fear looking foolish. Buying before a dip feels like embarrassment.

Not buying before a rally feels like missing out.

Either way, your brain is ready to send you an invoice for emotional damage.

A Bull Market Survival Kit (No Cape Required)

1) Choose an asset allocation you can actually live with

Diversification and asset allocation aren’t just textbook conceptsthey’re emotional shock absorbers.

A portfolio that’s 100% stocks might be optimal on paper for some time horizons, but if it makes you panic-sell during a drawdown,

it’s not “optimal” in real life.

The best allocation is the one you can hold through ugly weeks without turning your retirement plan into an improv comedy routine.

If bonds, cash reserves, or diversified funds help you stay invested, they’re not “drag.” They’re insurance against your future self.

2) Automate contributions (and stop negotiating with your feelings)

Bull markets tempt people to wait for a dip. Bear markets tempt people to stop investing altogether.

Automation is the antidote. Regular investingthrough retirement plans or scheduled depositsreduces the chances you’ll sit out a rally

while waiting for the “perfect” entry that never arrives.

3) Keep a “sleep-at-night” buffer

A solid emergency fund won’t maximize returns, but it can prevent forced selling.

When life happensjob changes, medical bills, surprise roof problemscash on hand can keep your long-term investments doing long-term things.

4) Rebalance with rules, not vibes

Rebalancing is the grown-up version of “buy low, sell high.” It’s a mechanical process:

trim what’s grown beyond your target weight and add to what’s lagged.

Done thoughtfully, it reduces concentration risk and keeps your portfolio aligned with your risk tolerance.

The key is to use a schedule or thresholdsquarterly, annually, or bands like “rebalance when an asset class drifts 5% off target.”

If you wait until you feel like rebalancing, you’ll do it exactly when you’re most emotional (which is… not ideal).

5) Build “news hygiene” into your plan

Markets move on narratives. Narratives move on adrenaline.

If you consume financial news like it’s breaking-weather coverage (“Category 5 Selloff Approaching!”), you’ll be trained to react.

Try a simple rule: check markets on a schedule, not a compulsion. Weekly or monthly is plenty for many long-term investors.

Your portfolio does not need hourly supervision. It’s not a sourdough starter.

Concrete Examples: What “Staying Invested” Looks Like

Example A: The investor who kept contributing during a scary drop

Imagine someone contributing to a 401(k) through a sharp selloff. They don’t “win” because they predicted the bottom.

They win because they didn’t require perfect timing.

As prices fell, each paycheck bought more shares. When markets eventually recovered, those shares participated in the rebound.

Example B: The investor who avoided the “all cash until it feels safe” trap

Another common story: an investor sells after a scary decline, waits for “confirmation,” and misses the early phase of the recovery.

By the time things feel safe, prices are higher and the investor re-enters reluctantlyoften right before the next pullback.

That’s how you create volatility in your own returns, even if the market’s long-term path is up.

Example C: The investor who diversified away from “the one thing that worked”

In many bull stretches, one area becomes the hero of the year. It’s tempting to pile in.

Diversification means admitting you don’t know which segment will lead nextand you don’t need to.

It also means you’re less likely to get emotionally wrecked when leadership inevitably rotates.

How to Prepare for the End of a Bull Market (Without Pretending You Can Predict It)

You don’t need a crystal ball. You need a plan that works across regimes:

expansion, slowdown, inflation scares, rate cuts, rate hikes, election years, and “why is everybody yelling on TV?” years.

- Match money to time horizon: short-term needs in safer assets; long-term goals in growth assets.

- Reduce single-point-of-failure risks: avoid extreme concentration in one stock, sector, or theme.

- Know your “panic threshold” now: if a 20% drop would make you bail, your risk level may be too high.

- Keep costs and taxes in view: fees, frequent trading, and short-term gains can quietly erode returns.

The goal isn’t to make volatility disappear. The goal is to make volatility survivableso you can stay in the game long enough for compounding to matter.

Conclusion: Bull Markets Aren’t a Free LunchThey’re a Long Recipe

Bull markets look easy after the fact because the ending is known. Living through them is harder because the next headline always feels like it could be “the one.”

But the pattern is consistent: volatility shows up, investors feel tempted to act, and discipline is rewarded over time more often than drama is.

If you take one thing from this: a bull market is not a straight line. It’s a noisy climb with frequent “are we there yet?” moments.

Your job isn’t to feel confident every day. Your job is to follow a plan on the days you don’t.

Real-Life Bull Market Lessons ( of Experience)

Experience #1: “I only sold a little… and then I couldn’t get back in.”

A very common bull-market story starts with good intentions. An investor sees a sudden 8–12% drop and thinks, “I’ll just reduce risk for a bit.”

They sell part of their stock funds and promise themselves they’ll buy back when the market calms down. Then the market bouncesfast.

Now the investor feels punished for being “careful,” so they wait for another dip. Another dip comes, but it’s scary again, so they wait for “confirmation.”

Weeks later, prices are higher, and the investor reluctantly buys back… right before another pullback, which feels like proof they were wrong.

The lesson isn’t that selling is always bad. It’s that partial exits often turn into long delays because re-entry is emotionally harder than the sale.

You need an explicit rule for getting back in, or “temporary” decisions become permanent detours.

Experience #2: “I chased the hottest thing and accidentally built a stress portfolio.”

Bull markets create celebrity stocks, celebrity sectors, and celebrity narratives. The investor who starts diversified can slowly drift into a theme-heavy portfolio:

a little more of what’s winning, a little less of what’s boring, until the portfolio’s mood depends on a single corner of the market.

When that corner wobbles, the investor’s confidence wobbles with it. They start checking prices more often, reading more commentary, and making more tweaks.

The portfolio becomes less about goals and more about entertainmentexcept it’s the kind of entertainment where you pay to be stressed.

The lesson: diversification is not just a return strategy; it’s a behavior strategy. A portfolio that is “too exciting” invites constant interference.

Many investors do better with something slightly less thrilling that they can hold through rotations.

Experience #3: “My best investing year felt awful.”

This one surprises people: some of the strongest long-term investing outcomes happen in years that feel emotionally terrible.

The investor lives through multiple pullbacks, unsettling headlines, and at least one moment of “maybe I should just stop.”

They keep contributing because it’s automated. They rebalance once because it’s on the calendar. They ignore a few tempting predictions because

they’ve learned that forecasts are often just well-dressed guesses. At year-end, they realize the portfolio is up meaningfully

but their memory is dominated by the stressful weeks.

The lesson: feelings are lagging indicators. Your emotional experience of a bull market can be negative even when the financial result is positive.

That’s why you build process. Process doesn’t require you to be brave; it requires you to be consistent.

Put together, these experiences point to the same conclusion: the biggest threat in a bull market isn’t that the market goes down.

It’s that you interrupt compounding with perfectly human reactionsfear, FOMO, regret, and the urge to “optimize” at the worst moments.

A bull market rewards patience, but patience is a skill you practice in discomfort.