Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What This Article Helps You Do

- Why Fast Thinkers Don’t Slow Down (Even When You Ask Nicely)

- The “Fast Thinker” Profile: What It Looks Like in Real Classrooms

- Teach the Brain’s Shortcuts (So Students Stop Trusting Them Blindly)

- Four High-Impact Classroom Strategies That Actually Slow Thinking

- Thinking Routines That Force Slow, High-Quality Reasoning

- Productive Struggle: The Healthy Kind of “Ugh”

- Executive Function Supports: Training Wheels for Slow Thinking (In a Good Way)

- Assessment That Rewards Depth (So Students Stop Worshiping Speed)

- Concrete Examples: What “Slow Down” Looks Like in Different Subjects

- Troubleshooting: When Slowing Down Backfires

- Experiences Related to Getting Fast Thinkers to Slow Down (Realistic Classroom Snapshots)

- SEO Tags

Some students are mental sprinters. You ask a question, and their hands shoot up like they’re

competing for an imaginary trophy labeled Fastest Brain in the West. It’s impressiveuntil

the answers get sloppy, the reasoning is thin, and the same “quick mistake” shows up again and again

like a sitcom character who refuses to leave the set.

The goal isn’t to “fix” fast thinkers. Speed can be a gift. But in learning, speed without

self-monitoring is like driving a sports car with no brakes: thrilling for a moment, expensive later.

What we’re really teaching is cognitive flexibilityknowing when to use quick, intuitive

thinking and when to shift into slow, deliberate, analytical thinking.

What This Article Helps You Do

- Recognize why fast thinkers rush (and why it feels good to them).

- Teach students how the brain’s shortcuts can cause confident mistakes.

- Use classroom routines that reward reasoning, not racing.

- Build “pause-and-check” habits with metacognitive prompts and executive function supports.

- Turn productive struggle into a skillnot a meltdown.

Why Fast Thinkers Don’t Slow Down (Even When You Ask Nicely)

Fast thinking is efficient. It’s the brain’s “autopilot”helpful for everyday decisions, quick

comprehension, and noticing patterns. The problem is that autopilot can also produce

confident wrong answers, especially when a task requires careful reasoning or multiple steps.

A classic classroom-friendly example: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 total. The bat costs $1 more than

the ball. How much does the ball cost?” Many students blurt “10 cents.” It feels right, but it’s wrong

(the ball is 5 cents). That moment is pure goldnot for embarrassing kids, but for teaching a big idea:

the first answer that pops up isn’t always the best answer.

Fast thinkers often have three powerful forces working in their favor:

- Momentum: once they start, they want to finishfast.

- Confidence: quick success in the past convinces them that speed equals skill.

- Attention economics: slowing down feels like extra effort (and effort is not always the vibe).

If we want students to slow down, we can’t rely on “Be careful!” and hope for magic. We need

structures that make slow thinking normal, useful, andyesrewarding.

The “Fast Thinker” Profile: What It Looks Like in Real Classrooms

Not every quick student is the same, but patterns show up across grade levels and subjects.

Watch for these common “speed tells”:

Academic speed tells

- Skips directions, then asks, “Wait, what are we doing?” (iconic)

- Finishes first but makes avoidable errorssign mistakes, missing units, misread questions

- Gives answers with little evidence (“I just know”) and resists explaining reasoning

- Chooses the fastest strategy even when a more accurate one exists

Discussion speed tells

- Blurts or dominates conversation before peers have thinking time

- Answers the teacher’s question but ignores the question’s deeper “why”

- Moves on quickly when challenged instead of revising their thinking

The aim isn’t to label students. It’s to identify where a “fast thinking habit” is getting in the way of

deeper learningthen teach a better habit.

Teach the Brain’s Shortcuts (So Students Stop Trusting Them Blindly)

One of the smartest moves educators can make is explainingage-appropriatelyhow thinking works.

When students learn that the mind uses shortcuts, they’re more likely to check their work instead of

assuming their first instinct is correct.

Make “fast vs. slow thinking” a shared classroom language

You don’t need a neuroscience degree. Try something like:

- Fast thinking: quick, automatic, low-effort, great for simple patterns.

- Slow thinking: deliberate, effortful, logical, better for multi-step problems and evaluating claims.

Then reinforce it with quick moments:

“That answer might be fast-thinking. Let’s switch to slow-thinking and check.”

Use “illusion busters” to build intellectual humility

Fast thinkers often overestimate what they know because they’ve been successful quickly before.

A helpful approach is having students explain a concept out loud (or in writing) as if teaching

someone who has never seen it. That act of explanation reveals gaps:

“Oh… I know the definition, but I can’t explain the mechanism.”

This is how you build a classroom culture of intellectual humility: confidence plus careful checking,

not confidence plus vibes.

Four High-Impact Classroom Strategies That Actually Slow Thinking

Slowing down isn’t a pep talkit’s a design problem. Here are strategies that create the conditions

for slow, methodical thinking while still honoring students who think quickly.

1) Increase “Wait Time” (Without Making It Awkward)

Research on classroom questioning suggests that typical pauses after a teacher question are often short.

Increasing wait timecommonly to around 3 seconds or moreis linked with better-quality responses,

more complex explanations, and improved student participation.

Practical moves:

- Silent count: ask the question, then silently count to three before calling on anyone.

- Write-first: “No hands until you’ve written a first draft answer.”

- Turn-and-talk: “Explain your thinking to a partner before we share out.”

Wait time helps fast thinkers, toobecause it gently forces them to double-check instead of blurting.

2) Outlaw “I’m Done” (Replace It With Better Questions)

Fast thinkers love finishing. So don’t fight that impulseredirect it.

Make “I’m done” illegal in your classroom (friendly illegal, like pineapple on pizza in certain states).

Replace it with reflection prompts:

- How can I make this better?

- What should I reread?

- How can I check my work?

- Can I solve it a second way?

This shifts the finish line from “completed” to “quality checked.”

3) Teach Students to Spot Cognitive Bias in Their Own Lives

Students slow down more readily when they see why it matters outside school. Invite them to collect

“brain shortcut stories” from daily life: jumping to conclusions online, trusting a confident influencer,

believing something because “everyone in my group thinks it,” or misremembering where they heard a claim.

A simple routine: students write a short story about a time their brain made a quick assumption,

then answer: What would slow thinking have looked like?

4) Build a Culture of Accountability: “Where Did You Hear That?”

Fast thinking shows up in discussion, tooespecially when students repeat claims without tracking sources.

Normalize a respectful classroom follow-up:

“Where did you hear that?”

This isn’t a “gotcha.” It’s a thinking habit. Students learn to connect information back to evidence,

evaluate credibility, and avoid accidental plagiarism or misinformation-sharing.

Thinking Routines That Force Slow, High-Quality Reasoning

Routines are the secret sauce because they reduce decision fatigue. Students don’t have to guess

how to thinkthey follow a reliable pathway. A few routines are especially good at slowing down

fast thinkers.

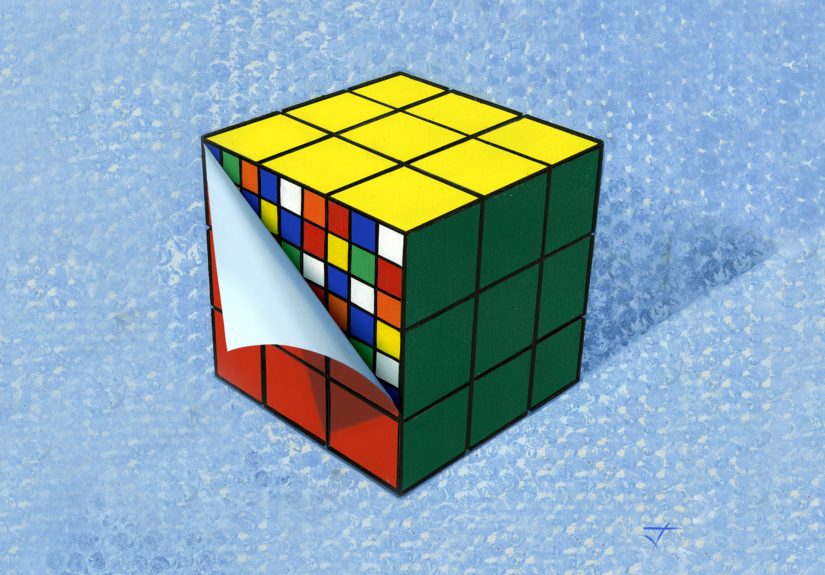

See–Think–Wonder (slow looking before fast conclusions)

Put an image, quote, graph, historical photo, science phenomenon, or math visual on the board.

Then ask students to respond in three parts:

- See: What do you notice? (Observations onlyno interpretations yet.)

- Think: What do you think is going on? (Interpretations with reasons.)

- Wonder: What questions do you have?

This routine quietly prevents “first thought = final answer,” and it gives fast thinkers a structured way

to deepen instead of dominate.

Claim–Evidence–Reasoning (CER)

CER is a classic “slow down and prove it” structure:

- Claim: What do you think?

- Evidence: What data/text supports it?

- Reasoning: Why does that evidence support the claim?

The best part: CER turns speed into a starting point, not a finish line.

Reverse the task (flip their thinking)

Ask students to argue the opposite, find a counterexample, or identify a common mistake someone might make.

Reversing forces students to pause, examine assumptions, and strengthen cognitive flexibility.

Productive Struggle: The Healthy Kind of “Ugh”

Fast thinkers often dislike struggle because they’re used to instant success. But deep learning usually

requires grapplingespecially in math, writing, and scientific reasoning. The key is making struggle

productive, not punishing.

In math education, “productive struggle” is often described as giving students opportunities and support

to wrestle with ideas and relationshipsnot simply chase correct answers.

How to make struggle productive (and not a crisis)

- Choose tasks with multiple entry points: so fast and slower processors can start.

- Anticipate common errors: then design questions that nudge, not rescue.

- Praise strategy use, not just correctness: “I like how you checked a second method.”

- Use “just-right” scaffolds: hints, partially worked examples, or self-explanation prompts.

A helpful teacher move is to treat mistakes like data:

“Interestingwhat step made sense at the time? What did you assume?”

That keeps fast thinkers engaged instead of embarrassed.

Executive Function Supports: Training Wheels for Slow Thinking (In a Good Way)

For some students, rushing isn’t just a habitit’s tied to executive function skills like planning,

inhibition, working memory, and self-monitoring. If we want students to slow down, we can provide

supports that make slow thinking easier to execute.

Simple tools that work across subjects

- Checklists: “Read twice, underline the question, show evidence, check units, review.”

- Timers with purpose: “You have 2 minutes to think silently before any sharing.”

- Chunking: break tasks into steps with mini-deadlines (reduces impulsive skipping).

- Progress monitoring: “Circle the step you’re on; star the step you want to revisit.”

Regulation resets (when speed is anxiety in disguise)

Sometimes students rush because they’re uncomfortable with uncertainty. A quick self-regulation reset

like a brief breathing routine or “pause and name the feeling”can help them re-enter the task with

better control.

The teaching message becomes: “Your brain can handle this. We’re not racing. We’re thinking.”

Assessment That Rewards Depth (So Students Stop Worshiping Speed)

Students optimize for what “counts.” If the classroom reward system celebrates speed, you’ll get speed.

If it celebrates reasoning, revision, and evidence, you’ll get better thinking.

Easy grading tweaks that promote slow thinking

- Points for process: reasoning steps, annotations, evidence, revisions, or error analysis.

- Second-chance learning: allow corrections with short reflection: “What did I miss and why?”

- Require a “check”: students submit an answer plus a verification method.

Practice retrieval to build durable understanding

Retrieval practice (low-stakes quizzing, brain dumps, flash prompts) supports learning by requiring students

to pull knowledge out of memory. It can also slow students down in a good way: they have to reflect,

reconstruct, and monitor what they truly knowno autopilot highlighting.

Concrete Examples: What “Slow Down” Looks Like in Different Subjects

Math

- Before solving: “What is the question asking in your own words?”

- During solving: “Show a second strategy or a quick estimate to check reasonableness.”

- After solving: “Find one place someone could make a common mistake.”

English/ELA

- Reading: pause after a paragraph to summarize and ask, “What evidence supports that?”

- Writing: treat draft one as “thinking on paper,” then require a revision pass with a checklist.

- Discussion: “Say the claim, then quote the line that made you think it.”

Science

- Lab work: “Predict first, then test, then explain the mismatch.”

- CER: claim + evidence + reasoning before the conclusion “counts.”

- Data reading: “What do you observe in the graph before interpreting it?”

Social Studies / Media Literacy

- Source checks: purpose, author expertise, and cross-checking claims before sharing.

- Bias spotting: identify a possible bias, then find a counterpoint or missing perspective.

- Accountability routine: “Where did you hear that?” + “What would confirm it?”

Troubleshooting: When Slowing Down Backfires

Sometimes “slow down” turns into “stuck,” “bored,” or “frustrated.” Here’s how to keep it productive:

- If fast thinkers get bored: add extension prompts (alternate methods, counterexamples, teach-a-peer).

- If students freeze: use sentence starters, partial examples, or guided questions (not full solutions).

- If anxiety drives rushing: normalize uncertainty and provide a predictable thinking routine.

- If impulsivity is a barrier: use visual reminders, timers, checklists, and structured turn-taking.

The aim is to build a habit: pause, plan, execute, check. Over time, the training wheels come off.

Experiences Related to Getting Fast Thinkers to Slow Down (Realistic Classroom Snapshots)

Teachers often describe the “fast thinker dilemma” in the same way: the student is bright, engaged,

and quickyet their work looks like it was completed while riding a scooter downhill, holding a snack,

and waving at a friend. The patterns repeat across grade levels, but the fixes are surprisingly similar:

make slow thinking visible, expected, and worth the effort.

Snapshot 1: The Math Race That Nobody Officially Started. In a middle school class, students

begin independent practice and a few finish in record time. You can feel the invisible leaderboard:

first done, best done. The teacher doesn’t scold speed; instead, she redirects it. “If you’re finished,

you’re not done. Choose one: (1) solve again a different way, (2) write a one-sentence explanation of

why your method works, or (3) find the most likely mistake someone would make and explain how to avoid it.”

Within a week, the “fast finishers” stop sprinting to the end because the end now includes a thinking task.

Their speed becomes useful: they produce alternate strategies and error analyses that help classmates.

Snapshot 2: The ELA Discussion Dominator. In a ninth-grade discussion, one student answers

every question instantly. It’s not mean; it’s momentum. The teacher adds a simple protocol: everyone

writes a response first, then shares. The fast thinker still shinesbut now their first thought has to survive

thirty seconds of paper. The student begins adding quotes, revising claims, and occasionally crossing out an

initial “hot take.” A month later, the student still participates often, but they also ask more questions and

build on peers’ points instead of jumping straight to closure.

Snapshot 3: The Science Lab “Conclusion First” Problem. In labs, some students rush to the

conclusion before the data has finished saying hello. A teacher introduces a “slow science” habit:

observations first, interpretations second, conclusion last. Students must fill three boxesWhat I observed,

What I think it means, and What I still wonder. Fast thinkers initially find it annoying (“Can’t we just

write the answer?”), but the teacher frames it as authentic scientific thinking. Over time, the same students

begin noticing anomalies, questioning assumptions, and designing better follow-up tests. Their speed shifts

from “finish fast” to “notice more.”

Snapshot 4: The Test Review Illusion. In test prep season, fast thinkers often “study” by reading

notes quickly and feeling confident. A teacher changes the routine: students must explain a concept out loud

(to a partner or as a quick recording) and then list what felt fuzzy. The first round is humblingin a healthy way.

Students discover the difference between recognizing words and understanding ideas. The fast thinkers don’t lose

their confidence; they upgrade it. Their new flex becomes accuracy and clarity, not speed.

Across these snapshots, the common thread is that slowing down isn’t presented as punishment. It’s presented as

craft. Just like athletes don’t “wing it” on form, thinkers don’t “wing it” on reasoning. When teachers

build predictable routineswait time, write-first, show-your-thinking, evidence requirements, revision prompts,

and self-checklistsstudents learn that slow thinking is not the opposite of being smart. It’s what smart looks like

when the stakes are real.

And the best surprise? Many fast thinkers eventually report that slowing down feels less stressful.

They stop relying on fragile confidence and start trusting a stronger system: pause, think, prove, and check.

That’s not just a classroom skill. That’s a life skill.

SEO Tags