Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- 1) First, Decide What “Equation Solver” You’re Actually Building

- 2) Solver Design That Doesn’t Ruin Your Day

- 3) TI-83/84 Family (TI-83 Plus, TI-84 Plus, TI-84 Plus CE): TI-BASIC Root Solvers

- A) Quick win: use the built-in numeric solver for manual checks

- B) Programmatic root finding with solve( … )

- Example 1: A general root solver (Y1 as f(X))

- Example 2: A “no fancy tokens” bisection solver you can port anywhere

- C) Quadratic solver (fast, exact-ish, and popular for a reason)

- D) Systems of equations (TI-83/84: matrices are your friend)

- 4) TI-89 / TI-92 / Voyage 200: You Get Symbolic Power (Use It Wisely)

- 5) TI-Nspire Family: TI-Basic vs Python (and the “Wait, Why Can’t Python Do That?” Moment)

- 6) “All TI Calculators” Checklist: Make Your Solver Feel Professional

- 7) Real-World Experiences: What It’s Like to Actually Build and Use These Solvers (≈)

- Conclusion

Let’s be honest: most of us don’t buy a TI graphing calculator because we love typing parentheses with the intensity of a courtroom stenographer.

We buy it because at some point, an equation looks at us funny and we want the calculator to handle it.

The good news: you can program solid equation solvers on essentially every TI graphing calculator familyTI-83/84, TI-89/92/Voyage 200, and TI-Nspireif you design the solver the right way.

The even better news: you don’t need to be a wizard, just a reasonably stubborn human with a plan.

This guide shows how to build equation solvers that feel “native” on each model: menus, prompts, safe inputs, sensible stopping rules, and methods that actually converge.

We’ll cover single-variable numeric solvers (roots), quick quadratic solvers, and basic systems (especially linear systems).

We’ll also show how to reuse the same solver logic across calculators with only small syntax changes.

1) First, Decide What “Equation Solver” You’re Actually Building

“Solve an equation” can mean wildly different things depending on the calculator:

- Numeric root finding: find x such that f(x)=0 (or left=right converted to 0). This is the workhorse on TI-83/84 and still useful everywhere.

- Symbolic solving: exact solutions like x = (−b ± √(b²−4ac)) / (2a). TI-89 and TI-Nspire CAS are great at this. TI-83/84 are not (unless you program the formula yourself).

- Systems solving: multiple equations, multiple unknowns. Linear systems can be solved by matrix methods on many models; nonlinear systems are possible but require more care.

A practical “all-calculator” approach is: build a numeric solver that finds real roots, then add “special-case” solvers (quadratics, linear systems) for speed and reliability.

This mirrors how built-in numeric solvers work on TI-84-family calculators and how root-finders are described in TI programming references.[1]

Core idea you can port everywhere

Write your solver as a loop that repeats:

evaluate → update guess → check stop condition → quit or continue.

That’s it. Everything else is user interface and damage control.

2) Solver Design That Doesn’t Ruin Your Day

Input style (pick one)

- “Function stored in Y1” (TI-83/84 style): user types f(X) into Y1, your program reads/evaluates Y1.

- Coefficient prompts (best for quadratics/linears): user enters A, B, C; you compute directly.

- Expression-as-text: user types a string expression; you convert/store it to a function (works on some models, but can be finicky).

Stop conditions (don’t skip this)

A solver that never stops is not “powerful,” it’s a tiny hostage situation. Use one or more:

- Function tolerance: |f(x)| < TOL

- Step tolerance: |x_new − x_old| < TOL

- Iteration limit: stop after N steps (and admit defeat politely)

Choose a method

- Bisection: slow but reliable if you have a sign change (f(a)·f(b)<0). Great “default.”

- Newton’s Method: fast when it works, moody when it doesn’t. Useful with a decent starting guess and a derivative (or a numerical derivative).

- Built-in root finders (when available): TI-83/84 have a built-in root finder command/token and an interactive numeric solver.[1]

If you want a solver that feels “professional,” combine methods:

start with bisection to get close, then switch to Newton for speed.

That combo is like using a seatbelt and a good playlist.

3) TI-83/84 Family (TI-83 Plus, TI-84 Plus, TI-84 Plus CE): TI-BASIC Root Solvers

On the TI-83/84 family, the most “universal” equation-solver program is a numeric root finder for f(X)=0.

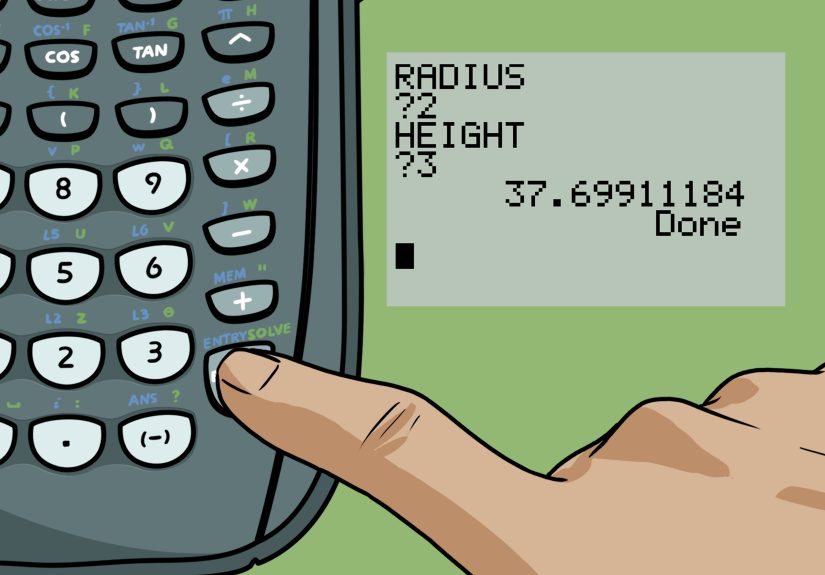

These calculators have an interactive numeric solver and also a callable root-finding command/token designed for programs.[2]

A) Quick win: use the built-in numeric solver for manual checks

If you’re testing your program (or sanity), the TI-84-family numeric solver expects the equation in the form 0= and uses a guess to find a real solution.[2]

That’s the same mental model your program should use: “Convert to zero, give a guess, solve.”

B) Programmatic root finding with solve( … )

The TI-83/84 family includes a programmable solve( command that attempts to find a real root of expression=0 given a variable and a guess, optionally with bounds.[1]

In plain English: “Find X so that f(X)=0, starting from this guess.”

Example 1: A general root solver (Y1 as f(X))

This is a clean pattern because the user can type any function into Y1 (like X^3-2X-5) and your program finds a root.

Notes that matter:

- A and B are bounds. If you can provide a bracket where the root exists, convergence improves and weird answers decrease.[1]

- T is your tolerance fallback; you can also use it in your own loop if you implement bisection manually.

- R is the root guess the calculator returns; you verify by evaluating Y1(R).

Example 2: A “no fancy tokens” bisection solver you can port anywhere

If you want a solver that behaves consistently across models (and doesn’t rely on any specific built-in root command),

bisection is the easiest to implement.

This is slower than Newton’s Method, but it’s dependableespecially for test-day anxiety and functions that like to misbehave.

C) Quadratic solver (fast, exact-ish, and popular for a reason)

If your goal is “solve common school equations quickly,” a quadratic solver is a must-have.

You can implement it directly using the quadratic formula, and many classroom handouts use this as an early TI-83/84 programming project.[3]

(And yes: you should handle the discriminant so you don’t accidentally try to take √(−9) and pretend it’s fine.)

D) Systems of equations (TI-83/84: matrices are your friend)

For linear systems (like 2–3 equations in 2–3 unknowns), the TI-84 family can solve using matrices by entering an augmented matrix or using matrix operations.[4]

If you’re programming, you can either:

- build a menu-driven “matrix input helper,” then use built-in matrix tools, or

- code a tiny Gaussian elimination routine (more work, more bragging rights).

For most people, a program that prompts coefficients and stores them into matrix [A] is the sweet spot:

fast to enter, fewer typos, and the calculator’s matrix engine does the heavy lifting.[4]

4) TI-89 / TI-92 / Voyage 200: You Get Symbolic Power (Use It Wisely)

These models are basically the “equation-solving luxury sedan” of older TI lines.

They support a solve(equation, variable) command that returns real solutions, and a cSolve variant for complex solutions.[5]

They also support a dedicated system solver function for simultaneous linear systems.[6]

A) Single equation solver (symbolic)

In a program, you can prompt for coefficients and build the equation string/expression, then call solve.

The biggest “gotcha” is making sure your equation is structured exactly as the calculator expects (especially with fractions/parentheses),

which is emphasized in many TI-89 classroom references.[7]

B) A program pattern for quadratics on TI-89 family

C) Systems solver (linear systems)

For systems like:

3x + 3y − 4z = −3, −x + 2y + 5z = 18, 8x + 4y − 7z = −5,

TI documentation shows using a simultaneous-equations function to solve directly on these models.[6]

In programs, the common pattern is: prompt coefficients → build the system → call the system solver.

Practical advice: if your users are students, include a “sanity check” option that plugs solutions back into the original equations

(because nothing says “I trust this answer” like verifying it before the teacher does).

5) TI-Nspire Family: TI-Basic vs Python (and the “Wait, Why Can’t Python Do That?” Moment)

TI-Nspire calculators come in a few flavors (CAS vs non-CAS), but the programming story usually looks like this:

- TI-Basic scripts: great for calculator-style programs with prompts and menus.

- Python (on many newer models): great for readable numeric methods, but it’s not always wired into the calculator’s built-in CAS features.

TI’s own Python guidebook explains how the Python environment behaves (including shell/program state and how programs run within a document/problem).[8]

Also, a widely-cited limitation: TI-Nspire Python generally can’t call the calculator’s built-in math/CAS functions directly from Python code.[9]

Translation: you should implement your own numeric solver in Python (bisection/Newton), rather than expecting a magical “solve()” bridge.

A) A portable Python bisection solver (TI-Nspire Python)

This works on any platform that runs Python, but it’s especially nice on TI-Nspire because it’s readable and stable.

B) Newton’s Method (with numerical derivative)

If you want speed, Newton’s Method is a classic.

Many TI learning materials demonstrate Newton-style iteration as a practical root-finding approach, especially when students already know derivatives conceptually.[10]

On calculators, a numerical derivative is often simpler than symbolic differentiation.

Want your program to feel friendly? Add prompts for:

interval endpoints (for bisection), guess (for Newton), iteration cap, and tolerance.

Then print “No sign change” or “Bad derivative” instead of crashing like a drama queen.

6) “All TI Calculators” Checklist: Make Your Solver Feel Professional

User experience upgrades

- Menu options: “Root (Y1=0) / Quadratic / Linear System / Exit.”

- Default values: if user enters 0 iterations, use 40; if tolerance blank, use 1E-5.

- Validation: check sign change for bisection; check A≠0 for quadratics; check matrix dimensions for systems.

- Verification: show f(root) so users see whether the answer is actually a root.

- Multiple roots: encourage users to change guesses or brackets to find different solutions (especially for trig/polynomial functions). Built-in solvers behave this way too.[1]

Accuracy vs speed (pick your battles)

A “fast solver” that sometimes lies is worse than a “slow solver” that’s honest.

Bisection is honest. Newton is fast. Hybrid is the best friend you didn’t know you needed.

Don’t forget the real-world constraints

- Exam mode rules vary, and some exams care about programs/apps. Always check your test policy.

- Memory: older TI models have limited space; keep menus simple and reuse variables.

- Typing errors: prompts beat free-form expressions for anything with coefficients.

7) Real-World Experiences: What It’s Like to Actually Build and Use These Solvers (≈)

Here’s what tends to happen the first time you try to “program an equation solver” on a TI calculator:

you feel unstoppable for about three minutesright up until the solver returns a number that looks like it came from a fortune cookie.

It’s not that the calculator is “wrong.” It’s that equation solving is a negotiation, and your inputs are the terms of the contract.

The most common experience on TI-83/84 calculators is learning that guesses matter.

You enter a trig equation, hit solve, and suddenly your answer is a completely different root than your friend’s.

Same equation. Same calculator. Different guess. Different “nearest” solution.

Once you accept that reality, your programs get better fast: you start asking for a bracket (A and B) instead of one lonely guess,

you add a “try another guess” loop, and you print f(x) afterward so users can judge whether the root is good.

Another very real moment: the “NO SIGN CHANGE” message becomes your personal trainer.

At first it’s annoying. Later you realize it’s saving you.

When you force your program to require a sign change for bisection, it teaches users to think like problem-solvers:

graph first, estimate where the root is, then solve. That workflow also makes test-day behavior calmer.

Instead of hammering SOLVE ten times like it’s an elevator button, students learn to bracket the root on purpose.

On TI-89 and TI-Nspire CAS models, the experience flips: the calculator is so capable that users get overconfident.

They type a messy equation, forget parentheses, and then blame the device when the answer is weird.

The fix is surprisingly human: your program should be picky.

Ask for coefficients when you can.

If you must accept an expression, display it back to the user before solving.

And if you’re solving a system, always offer a “plug back in” verification screenbecause the fastest way to trust a solution is to see it satisfy the original equations.

If you use Python on TI-Nspire, there’s a classic experience too: you try to call a built-in solve feature from Python and discover it’s not that kind of party.

That limitation nudges you toward writing your own numeric methods, and honestly, that’s a hidden win.

Once you’ve written bisection and Newton in Python, you suddenly understand what your calculator has been doing behind the scenes for years.

You stop treating solvers like magic and start treating them like tools with conditions: they need continuity, good starting values, and realistic expectations.

The best long-term outcome of programming these solvers is that they change your habits:

you stop typing giant equations repeatedly, you build menus for common equation types, and you reuse code like a real developer.

Your calculator becomes less of a “button-mashing machine” and more of a personalized math assistant.

And yes, it’s a little satisfying when your friends ask, “How did you get your calculator to do that?” and you get to say,

“Oh, that? I taught it.”

Conclusion

Programming equation solvers across TI graphing calculators is mostly about choosing a method you can trust, designing inputs you can’t mess up,

and building a user flow that helps people get the right rootnot just a root.

Start with a reliable numeric root solver (bisection + optional Newton), add a quadratic solver for speed, and lean on matrix methods for linear systems.

On TI-89 and TI-Nspire CAS, take advantage of symbolic powerbut still verify.

If you do that, you’ll end up with solver programs that work across models, across classes, and across the kind of chaos only math homework can create.