Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Meet TRAPPIST-1: The Tiny Star With a Seriously Crowded Neighborhood

- Why Astronomers Expect (and Hope For) Hidden Giants

- Where Could a Gas Giant Hide in TRAPPIST-1?

- How Do You Hunt a Planet You Can’t See?

- So… Is TRAPPIST-1 Hiding a Gas Giant or Not?

- Why a Hidden Gas Giant Would Matter

- Chasing a Ghost Planet: An Experience From the Observatory

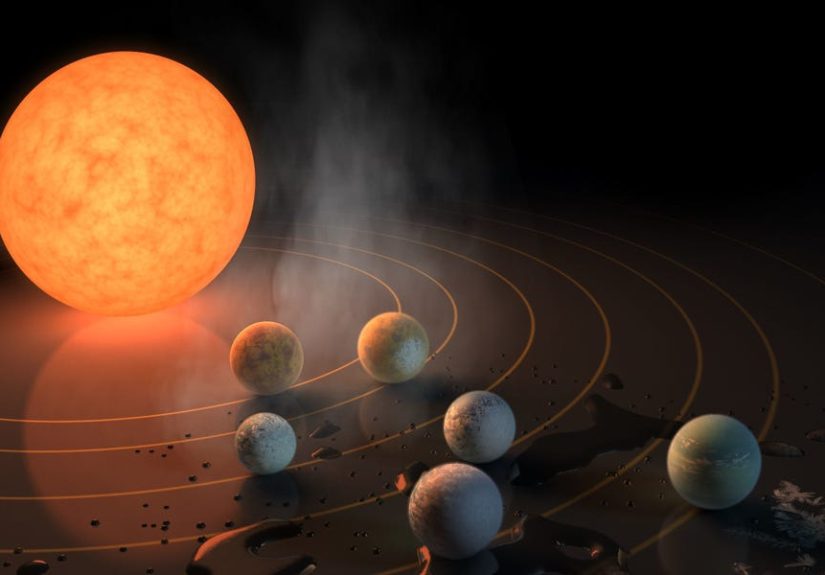

Forty light-years away, in the constellation Aquarius, there’s a tiny, dim star that keeps stealing the spotlight from much bigger, flashier suns. That star is TRAPPIST-1, an ultra-cool red dwarf with seven rocky, Earth-size planets crammed so close to it that their orbits make Mercury look like a recluse.

Those seven planets are celebrities in exoplanet science. Some sit in the star’s “just right” habitable zone, and they’re among the best targets we have for studying potentially Earth-like worlds. But astronomers are greedy in the best possible way: seven worlds are great, sure, but… what if there’s more?

Specifically: could the TRAPPIST-1 system be hiding a gas giant a big, Jupiter-like world lurking farther out, too faint and too slow to show itself easily? It’s a natural question, because our own Solar System has a similar layout: small rocky planets inside, beefy gas and ice giants outside. If TRAPPIST-1 turns out to follow that pattern too, it could tell us a lot about how planetary systems form around tiny stars.

The short answer: there’s no sign of a nearby gas giant, but a distant one hasn’t been ruled out yet. The long answer is way more fun so let’s dig in.

Meet TRAPPIST-1: The Tiny Star With a Seriously Crowded Neighborhood

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultra-cool red dwarf star with only about 9% of the Sun’s mass and roughly 12% of its radius barely larger than Jupiter in size, though much denser. It’s faint, emitting less than 0.1% of the Sun’s luminosity, and it glows mostly in infrared light, which is why infrared telescopes like Spitzer and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) love it.

Around this tiny star orbit seven known planets, all roughly Earth-sized, all packed inside an orbital distance smaller than Mercury’s track around the Sun. Their orbital periods range from about 1.5 days for the innermost planet to about 18.8 days for the outermost, TRAPPIST-1h. Three of them TRAPPIST-1e, f, and g sit in or near the star’s habitable zone, where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface under the right conditions.

Detailed analyses of their masses and radii, using transit timing variations (TTVs), show that these planets are mostly rocky and relatively low in density, with significant amounts of volatiles like water or other light components mixed in. That makes the system a dream laboratory for studying terrestrial planets and a great test case for figuring out whether small stars also build giant planets.

Why Astronomers Expect (and Hope For) Hidden Giants

In many planetary systems, large gas giants live farther from the star while smaller, rocky worlds cluster inside. Our Solar System does this in textbook fashion: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars near the Sun; then the gas and ice giants Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune out beyond the snow line. That outer population affects everything from comet delivery to the long-term stability of the inner planets.

So it’s natural to ask: if TRAPPIST-1 has seven tightly packed terrestrial planets, might there also be one or more gas giants farther out on wider orbits?

A 2017 study led by Alan Boss at the Carnegie Institution looked at exactly this question. Using high-precision astrometric observations of TRAPPIST-1 over five years from the du Pont telescope in Chile, the team searched for subtle “wobbles” in the star’s position that would betray the tug of a massive outer planet.

Their results were intriguing: they didn’t detect any gas giants directly, but they could set upper limits. The data rule out planets more massive than about 4.6 times Jupiter’s mass on a one-year orbit, and more massive than about 1.6 Jupiters on a five-year orbit. In other words, if a gas giant is there, it has to be relatively modest in mass or on a wider, slower orbit something closer to a Saturn or Neptune analog, or a cold, distant Jupiter that takes many years to go around the star.

Where Could a Gas Giant Hide in TRAPPIST-1?

Not in the Crowded Inner System

Inside the region where the seven known planets orbit, there’s essentially nowhere for a big gas giant to hide. The TRAPPIST-1 planets form a tightly packed “resonant chain”: their orbital periods are locked in near-exact ratios, causing them to gravitationally tug on each other in a predictable way.

These tugs show up as transit timing variations tiny shifts in when each planet crosses in front of the star. Astronomers have been measuring those TTVs for years with ground-based telescopes, Spitzer, Kepler/K2, Hubble, and now JWST. The observed timing pattern is beautifully explained by the seven known planets alone. A nearby Jupiter-mass world would seriously mess up that dance, causing extra timing signals that simply aren’t there.

On top of that, the system is very flat: the planets’ orbits are extremely coplanar, which also constrains any big additional body that could pump up their inclinations over time. Put simply, a close-in gas giant would leave loud dynamical fingerprints, and those fingerprints are missing.

The Quiet Outer Reaches: Still in Play

Farther out, though, the picture changes. The seven known planets all orbit within about 0.06 astronomical units (AU) of the star a fraction of Mercury’s distance from the Sun. Beyond that, the data get sparser. Transit surveys are less sensitive to long-period planets, and TRAPPIST-1 is too faint in visible light for ultra-precise radial-velocity measurements with current instruments.

This is where the astrometric work from CAPSCam comes in: it shows that while we don’t see any big wobble that would indicate a super-Jupiter, a lower-mass gas giant on a multi-year orbit is still allowed by the data. The outer TRAPPIST-1 system could host, say, a Saturn-mass planet or a group of smaller ice giants without violating current constraints.

In other words, if TRAPPIST-1 is hiding a gas giant, it’s likely doing it the same way your neighbor hides their junk: far out in the cosmic “backyard,” where we just haven’t looked carefully enough yet.

How Do You Hunt a Planet You Can’t See?

1. Transit Timing Variations: Reading the Clock

Transit timing variations are the Swiss-army knife of exoplanet dynamics. If planets in a system tug on each other, their transits drift slightly earlier or later than a perfectly regular schedule. Measure those offsets precisely, and you can infer the planets’ masses, sometimes even spot non-transiting planets.

For TRAPPIST-1, the TTVs are rich and complicated because the planets are in a long resonant chain. Models by multiple teams including Grimm and collaborators and later Agol and colleagues have used these variations to derive tight constraints on the planets’ masses and densities. A massive unseen planet in the inner system would throw those fits way off, so its absence in the data is strong evidence that there’s no inner gas giant.

2. Astrometry: Watching the Star Wobble

Astrometry is a more old-school, but still powerful, approach: you track the exact position of the star on the sky over years and look for small deviations from a straight path. If a big planet is orbiting, the star and planet actually orbit a shared center of mass, causing the star to wobble very slightly back and forth.

CAPSCam observations of TRAPPIST-1 over five years found no significant long-period wobble, leading to the current upper limits on possible gas giants (no more than 4.6 Jupiter masses at a one-year period, and no more than 1.6 Jupiters at a five-year period). That doesn’t prove there’s no giant planet, but it does mean that if one exists, it’s either relatively light or fairly distant.

3. Future Direct Detection and Infrared Surveys

Could we ever directly see a TRAPPIST-1 gas giant? Maybe. A cold, distant giant would be tricky to spot, but next-generation instruments on giant ground-based telescopes and continued high-precision astrometry (including from space missions) could reveal faint companions.

JWST is already focused on TRAPPIST-1’s inner planets, measuring their temperatures and searching for atmospheres. While it’s not optimized for finding distant cold giants in this particular system, the more precisely we understand the star and its inner planets, the easier it becomes to spot subtle anomalies that might hint at an outer companion.

So… Is TRAPPIST-1 Hiding a Gas Giant or Not?

Based on current observations, astronomers are confident about a few things:

- There is no Jupiter-like planet lurking just beyond the seven known planets. The TTV data and dynamical modeling would have revealed its gravitational effects by now.

- TRAPPIST-1 could still host one or more gas or ice giants at larger distances, on orbits of several years or more, as long as their masses stay below the current astrometric limits.

- We haven’t yet mapped the outer system with the same precision we’ve lavished on the inner seven planets so the door for a hidden giant remains open, just not wide.

In other words: if the TRAPPIST-1 system is hiding a gas giant, it’s playing a long game. It would be a relatively modest-mass planet on a slow, cold orbit, quietly circling far from the cozy, compact cluster of rocky worlds we already know.

Why a Hidden Gas Giant Would Matter

You might reasonably ask, “Okay, cool, but why should I care about one more big ball of gas?” (Aside from the fact that Jupiter has incredible storm aesthetics.)

A gas giant in TRAPPIST-1 would strongly shape the story of how the whole system formed:

- Disk physics and planet formation: Boss and colleagues showed that even very low-mass stars like TRAPPIST-1 could form gas giants through “disk instability,” where the protoplanetary disk breaks into clumps that collapse quickly into massive planets. Confirming a giant around such a tiny star would be a huge win for that model.

- Water and volatiles delivery: Many simulations suggest that outer icy bodies and migrating giants help deliver water and other volatiles to inner rocky planets. TRAPPIST-1’s known planets appear to contain significant water and other low-density materials. A distant giant could have played a role in scattering icy planetesimals inward early in the system’s history.

- Long-term habitability: Giant planets can either protect inner worlds by deflecting comets, or destabilize them by stirring up orbits. Whether a hypothetical TRAPPIST-1 giant would be a “cosmic bodyguard” or a chaos agent depends on its mass and orbit another reason astronomers want to know if it exists.

For scientists thinking about life and panspermia, the spread of life between planets TRAPPIST-1 is already fascinating. The three habitable-zone planets are so close together that material blasted off one world by an impact could reach another relatively easily, potentially spreading biology. A distant gas giant would add another ingredient to that cosmic experiment.

Chasing a Ghost Planet: An Experience From the Observatory

Imagine you’re on the night shift at an observatory in Chile. The air is thin and dry, the Milky Way looks like spilled sugar across the sky, and somewhere in your queue is a small, unassuming red dwarf known as TRAPPIST-1. On your screen, it’s just a faint dot no cinematic lens flares, no obviously epic vibes. If it weren’t for the papers and headlines, you’d never guess that dot has seven Earth-size worlds circling it.

Your job tonight isn’t to look at those inner planets. Other telescopes and teams have their timing down to the minute, watching transits to measure atmospheres or confirm orbital periods. You’re doing something slower and more patient: checking whether the star’s position creeps back and forth ever so slightly over months and years.

The individual images don’t look like anything special. A few pixels here, a few pixels there, some cosmic rays to clean up, some background stars to use as reference points. You calibrate, subtract, fit, and cross-match. On any single night, it’s mostly just numbers and noise you might be more likely to be distracted by how badly you want a second cup of coffee than by any dramatic “Aha!” moment.

But as the seasons stack up, the data start to form a pattern. You correct for Earth’s motion, for parallax, for the star’s own proper motion across the sky. What’s left the residual wobble is where a hidden planet would reveal itself. A closer, more massive giant would pull the star into a wider loop; a lighter, distant planet would trace out a much subtler curve.

When you run the final fit, there’s a little thrill: this is the moment where, if TRAPPIST-1 is hiding something big, you’d see it peek out of the noise. Instead, what you get is… limits. The residuals are small. The fits say, “No more than 4.6 Jupiters at a one-year orbit, no more than 1.6 at five years.” That might sound anticlimactic, but in astronomy, a clean “no” or a strong “not that big” is real progress.

You walk outside at dawn. TRAPPIST-1 is below the horizon now, invisible. But you know that somewhere out there, seven rocky planets are whipping around a dim little star in a tight gravitational choreography we can predict down to the minute. And maybe, far beyond those inner worlds, a quieter, colder planet is circling too slowly for us to catch yet.

That’s what “hiding a gas giant” really means in modern exoplanet science: not a dramatic reveal of a huge new world overnight, but a long, careful tightening of the net, until either a signal emerges or the possibilities shrink to almost nothing. TRAPPIST-1 hasn’t given up that secret yet, but the hunt is very much on.