Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Metastatic” Really Means (and Why the Liver Gets Invited)

- How Common Is Liver Metastasis in Lung Cancer?

- Symptoms: When the Liver Raises Its Hand

- Diagnosis: How Doctors Confirm Liver Metastases

- Treatment Strategy: Control the Whole Fire, Not Just One Spark

- Prognosis: The “Numbers” Conversation Without the Doom Scroll

- Questions to Ask Your Oncology Team

- Everyday Life Tips: Small Wins Matter

- Conclusion: The Liver Is Tough, and So Are You

- Real-World Experiences (500+ Words): What It Feels Like, Day to Day

If you’ve ever wished your lungs and liver would stop collaborating on “surprise projects,” you’re not alone.

When lung cancer spreads to the liver, it can feel like the disease has changed the rules mid-game.

The good news: modern treatment has more plays than evertargeted therapy, immunotherapy, smarter chemo,

precise radiation, and liver-directed techniques that sound like science fiction (in a helpful way).

This guide breaks down what it means when lung cancer spreads to the liver (also called liver metastases or

hepatic metastases), what symptoms to watch for, how doctors confirm the diagnosis, and how treatment is usually planned.

I’ll keep it medically accurate, but I won’t pretend this topic is fun. We’ll aim for “clear, honest, and a little human.”

Quick note: This article is educational, not medical advice. If you have new or worsening symptomsespecially jaundice, confusion, fever, or severe abdominal paincontact your care team promptly or seek urgent care.

What “Metastatic” Really Means (and Why the Liver Gets Invited)

Metastatic lung cancer means cancer cells from the original tumor in the lung have traveled to another organ and started growing there.

Even after it spreads, it’s still lung cancer at the cellular leveljust in a new zip code. So liver metastases from lung cancer are treated as

lung cancer, not primary liver cancer.

Cancer spreads mainly through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. And the liver?

It’s a high-traffic organ with a rich blood supply and a big job filtering blood and processing nutrients.

Unfortunately, that can make it a common destination for metastatic cells in general.

The National Cancer Institute notes the liver is among the most common sites where cancers spread.

Does liver spread automatically mean “stage 4”?

In most cases, cancer spread to a distant organ like the liver is considered advanced disease (often stage IV).

Staging still depends on the lung cancer type (non-small cell vs small cell), how extensive the spread is, and other factors.

Your oncology team will combine imaging, biopsy results, and sometimes molecular testing to define the stage and best treatment plan.

How Common Is Liver Metastasis in Lung Cancer?

The honest answer: it variesby lung cancer type, biology, and when the cancer is found.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is known for spreading early and quickly, while non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is more varied.

A major patient resource notes a high rate of metastases in SCLC and provides estimates for liver involvement that illustrate how often the liver can be affected.

(Translation: this isn’t rare, and it’s not “your fault.” It’s cancer doing cancer things.)

What matters most clinically isn’t just “is it there?” but also:

how much of the liver is involved, whether liver function is affected, what the tumor’s biomarkers show, and how well the cancer responds to systemic therapy.

Symptoms: When the Liver Raises Its Hand

Liver metastases can be sneaky. Some people have no symptoms at first, and the spread is found on a scan done for staging or follow-up.

When symptoms do show up, they often overlap with side effects from treatment or other conditionsso don’t self-diagnose, but do speak up early.

Common symptoms of lung cancer that has spread to the liver

- Right upper abdominal discomfort or pain (where the liver lives, quietly doing 500 jobs)

- Fatigue that feels heavier than “I didn’t sleep well”

- Nausea or feeling full quickly

- Loss of appetite and unintentional weight loss

- Jaundice (yellowing of skin/eyes), sometimes with dark urine and pale stools

- Itchy skin (yes, your liver can make you itchyrude but true)

- Swollen belly from fluid buildup (ascites)

- Leg swelling (edema) in some cases

- Fever or sweating

- Confusion in advanced situations where liver function is significantly impaired

Symptoms that deserve faster attention

Call your clinician sooner rather than later if you notice new jaundice, rapidly increasing abdominal swelling, confusion, persistent vomiting,

fever, or severe abdominal pain. Not all of these mean “the worst,” but they do mean “don’t wait it out.”

Diagnosis: How Doctors Confirm Liver Metastases

Confirming liver metastases is a mix of imaging, lab work, and sometimes tissue sampling.

The goal is to answer three big questions:

(1) Is this cancer? (2) Is it lung cancer spread? (3) What treatment targets it best?

Imaging: CT, PET, MRI (the “camera crew”)

Imaging is usually step one:

- CT scans are commonly used to detect lung cancer and evaluate spread to the liver.

- PET scans (often PET-CT) help identify metabolically active cancer spots throughout the body.

- MRI can be especially useful for characterizing liver lesions when more detail is needed.

- Ultrasound may also be used, especially for guiding procedures.

Blood tests: liver function and “how the liver is coping”

Doctors often check liver function tests (LFTs) and other labs to see how well the liver is working.

These labs don’t prove metastasis by themselves, but they matter for treatment safety.

If the liver is stressedby tumor involvement or by medication side effectsyour team may adjust drug choices or dosing.

Biopsy: when a sample settles the debate

Sometimes imaging is convincing enough. Other times, doctors take a tissue sample (biopsy) to confirm malignancy and verify the cancer type.

Biopsy can also unlock the next step: biomarker testing.

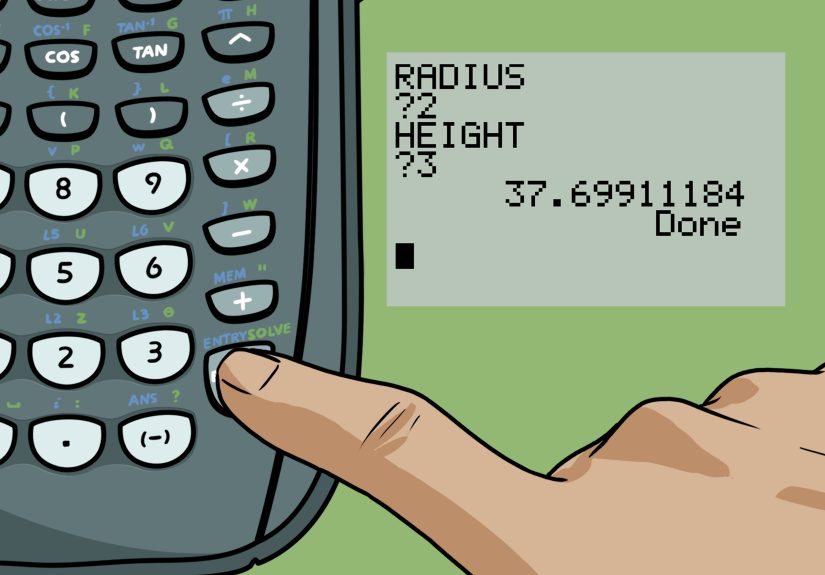

Molecular and biomarker testing: the “choose-your-weapon” step

For many people with NSCLC, especially advanced disease, tumor profiling (also called genomic testing or next-generation sequencing)

helps identify actionable targets. Commonly discussed gene alterations include EGFR, ALK, and KRAS, among others.

In addition, testing for PD-L1 can help guide immunotherapy decisions.

Treatment Strategy: Control the Whole Fire, Not Just One Spark

When lung cancer spreads to the liver, treatment usually focuses on systemic therapymedicine that treats cancer throughout the body.

That’s because liver metastases are rarely the only microscopic spread, even if scans show only a few spots.

Think of it as treating the whole ecosystem, not just one troublesome plant.

1) Systemic therapy: the backbone of treatment

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy remains a core option for many metastatic lung cancers, particularly when rapid disease control is needed.

In SCLC, chemotherapy is often central because of the cancer’s fast-growing nature, and it’s commonly paired with immunotherapy in extensive-stage disease.

Immunotherapy (checkpoint inhibitors)

Immunotherapy has changed the landscape for many people with NSCLC and some with SCLC.

Checkpoint inhibitors such as PD-1/PD-L1 blockers help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

Depending on tumor factors (including PD-L1 expression) and overall context, immunotherapy may be used alone or combined with chemotherapy.

Targeted therapy (when a driver mutation is found)

If testing shows an actionable “driver” alteration, targeted therapy can be a powerful optionoften with different side-effect profiles than chemo.

Targeted drugs are especially important in advanced NSCLC with certain genetic changes.

The key takeaway: testing matters. If you’re not sure whether comprehensive biomarker testing has been done, it’s reasonable to ask.

2) Liver-directed therapy: when focusing on the liver helps

Even in metastatic disease, doctors may recommend treatments aimed directly at liver lesions in specific situations, for example:

painful tumors, threatened bile ducts, limited (“oligometastatic”) spots, or when the liver is the main driver of symptoms.

These approaches don’t replace systemic therapy for most peoplebut they can be important teammates.

Precision radiation (including SBRT)

Techniques like stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) can deliver high-dose radiation to a liver lesion while limiting exposure to surrounding tissue.

Radiation may also be used palliativelymeaning to relieve symptoms quickly.

Ablation (heat or cold to destroy tumors)

Ablation uses heat (radiofrequency or microwave) or extreme cold (cryotherapy) to destroy tumors.

It’s typically considered when there are a limited number of tumors, and when location and liver function make it feasible.

Embolization and radioembolization (targeting tumors from the inside)

Interventional radiology procedures can deliver treatment through the liver’s blood supply.

Chemoembolization aims chemotherapy directly at tumors and restricts blood flow to them.

Radioembolization delivers radiation via tiny particles to help treat tumors while preserving as much normal liver as possible.

(Yes, it’s as cool as it soundsminus the reason you need it.)

Surgery (rare, but sometimes on the table)

Surgery for liver metastases from lung cancer is not common, but in carefully selected casesoften with very limited liver involvement and good control elsewhereit may be considered.

Your team’s decision depends on tumor biology, overall spread, and whether surgery would meaningfully improve outcomes or quality of life.

3) Supportive and palliative care: not “giving up,” but getting help

Palliative care focuses on symptom relief and quality of life at any stage of serious illness.

It can help manage pain, nausea, appetite changes, fatigue, anxiety, insomnia, and the emotional whiplash of scan results.

Many people wish they had started it earlier.

Practical symptom supports might include:

- Anti-nausea medications and appetite strategies

- Pain management plans (tailored to liver function and overall health)

- Drainage procedures for ascites in certain cases

- Nutrition counseling (because “just eat more” is not a plan)

- Support groups, counseling, and caregiver resources

Prognosis: The “Numbers” Conversation Without the Doom Scroll

Liver metastases usually indicate advanced disease, and they can be associated with a more challenging prognosis than lung cancer confined to the chest.

But prognosis isn’t a single number stamped on your forehead.

It’s shaped by many factors, including:

- Whether the cancer is NSCLC or SCLC

- How extensive liver involvement is and whether liver function is affected

- Presence of actionable mutations (which can open targeted options)

- PD-L1 expression and likelihood of immunotherapy benefit

- Overall health, weight, activity level, and other medical conditions

- How well the cancer responds to first-line treatment

If you want a practical way to frame it, try this:

Ask what the goal of treatment is right nowshrink tumors quickly, slow growth, relieve symptoms, maintain independence, or all of the above.

Goals can change over time, and that’s normal.

Questions to Ask Your Oncology Team

- Is the liver lesion definitely metastatic lung cancer, and do we need a biopsy to confirm?

- Have we done broad molecular profiling (NGS) and PD-L1 testing? If not, why?

- What is the recommended first-line systemic therapy, and what is the rationale?

- Are liver-directed treatments (SBRT, ablation, embolization) appropriate in my situation?

- How will we monitor liver function during treatment?

- What symptoms should trigger a call right away?

- Are there clinical trials that match my cancer type and biomarkers?

- Can palliative care be involved early to help with symptoms and stress?

Everyday Life Tips: Small Wins Matter

Living with metastatic lung cancer to the liver is not just about treatment cyclesit’s also about getting through Tuesdays.

A few practical, non-glamorous tips that often help:

Be honest about fatigue

Fatigue isn’t laziness; it’s biology. Ask about medication timing, anemia, sleep strategies, light activity, and whether symptoms suggest liver strain.

Some people do best with short walks; others need aggressive rest. Both can be “doing it right.”

Don’t freestyle supplements

Your liver processes medications and many supplements. “Natural” doesn’t automatically mean “safe for a stressed liver.”

Run vitamins, herbs, and CBD products by your care teamespecially during chemo, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy.

Eat for reality, not Instagram

When appetite is low, aim for protein and calories in tolerable formssmoothies, soups, eggs, yogurt, nut butters, nutrition drinks.

If nausea is an issue, small frequent meals often beat three big ones.

Plan for the practical stuff

Treatment can be expensive and time-consuming. Many patients benefit from asking early about:

insurance coverage for scans, financial assistance programs, transportation resources, and paperwork tips that make approvals smoother.

Conclusion: The Liver Is Tough, and So Are You

When lung cancer spreads to the liver, it’s a serious turnbut it’s not the end of options.

Diagnosis often relies on imaging and sometimes biopsy; treatment typically centers on systemic therapy guided by biomarkers,

with liver-directed procedures used strategically for symptom relief or limited disease situations.

Add palliative care early, ask about clinical trials, and keep your support system closebecause this is not a “solo sport.”

Real-World Experiences (500+ Words): What It Feels Like, Day to Day

Here’s the part people don’t always put in medical brochures: living with metastatic lung cancer to the liver is as much an emotional marathon

as it is a medical one. Many patients describe the moment they hear “it’s in the liver” as a strange mix of clarity and disbelief.

Clarity because the care plan often becomes more structuredmore tests, more appointments, more “we’re going to start treatment soon.”

Disbelief because your brain keeps trying to negotiate with reality. (“Maybe the scan is wrong.” “Maybe it’s a cyst.” “Maybe the liver is just… having a dramatic week.”)

The next experience is usually scan season: CT, PET-CT, MRI, labs, and sometimes a biopsy. The waiting can feel louder than the diagnosis itself.

People talk about “scanxiety”that tense, stomach-in-a-knot feeling that arrives before results and overstays its welcome.

One practical trick many patients use is creating a “results plan”: decide ahead of time who will be with you when results arrive,

what comfort routine you’ll do afterward (walk, favorite show, call a friend), and what questions you’ll ask no matter what the report says.

It doesn’t make the anxiety vanish, but it gives it less space to run your life.

Then comes treatment, and with it a new kind of routine: infusions, pills, symptom tracking, and learning a whole new vocabulary.

People often describe feeling torn between wanting to “fight” and wanting to “feel normal.” The truth is you can do both.

Sometimes “fighting” looks like showing up for chemo or immunotherapy; other times it looks like taking nausea meds early,

asking for a dose adjustment, or letting someone else make dinner because your energy budget is already in the red.

Symptoms linked to liver involvementlike nausea, appetite loss, itching, or right-sided abdominal discomfortcan be especially frustrating

because they’re not always dramatic, just persistent. It’s the daily drip of discomfort that wears people down.

Many patients find relief in practical micro-strategies: keep snacks simple and frequent, avoid strong smells when nauseated,

track which foods you tolerate, and report symptoms early rather than “toughing it out.”

Clinicians can’t help fix what they don’t know is happeningand you deserve comfort, not a trophy for silent suffering.

Caregivers experience their own whiplash. They’re often the ones learning medication schedules, coordinating rides, and translating medical language into real-life decisions.

A common caregiver challenge is feeling responsible for everything, including moods. A helpful mindset shift is this:

you can support someone without controlling the disease, and you can love someone without solving every problem.

Support groupsonline or in-personcan be a lifeline because they normalize feelings that are hard to say out loud.

Another shared experience is the way cancer rearranges time. People start living in “cycles” (two-week cycles, three-week cycles),

and life events get measured in “before the next scan” or “after this round.”

Many patients say the most meaningful progress isn’t always a dramatic tumor shrink on paperit’s being able to walk the dog again,

to sleep through the night, to laugh at a ridiculous meme, or to attend a family dinner without needing to leave early.

Those are real wins.

Finally, there’s the emotional truth that most people eventually learn: hope isn’t a single, fragile thing.

It evolves. At first, hope might be “cure.” Later, it might be “more time,” “fewer symptoms,” “a good month,” or “making it to a milestone.”

Hope can be big and small at the same time. And yesyou’re allowed to have humor, even here.

Sometimes laughter doesn’t mean you’re not taking it seriously; it means you’re still human in a situation that tries very hard to reduce you to a diagnosis.