Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Key Takeaways (Because We’re All Busy)

- What “Dry Powder” Really Means (And What It Definitely Doesn’t)

- How Big Is the Pile? The (Important) Answer Is: “It Depends.”

- Why Dry Powder Built Up: Four Forces, One Big Backlog

- So Is Dry Powder “Bad”? Not Exactly. It’s Pressure. Pressure Can Be Useful.

- The Real-World Impact on Deals: What Changes When Everyone Has Money?

- Zooming Out: Dry Powder Isn’t Just About Buying. It’s About Exiting, Too.

- Putting Dry Powder Into Perspective: Three Mental Models That Actually Help

- What LPs Can Do About It (Besides Muttering “Vintage Year Risk” Into Their Coffee)

- What GPs Can Do (Without Turning Deployment Into a Sport)

- Where This Might Go Next

- Field Notes: What Dry Powder Pressure Feels Like (500-ish Words of “Experience,” Minus the Mythology)

- Conclusion

“Dry powder” is one of those finance phrases that sounds like it was invented by someone who owns three Patagonia vests and one personality. But it’s also

a useful ideaespecially now, when private equity (PE) is sitting on a truly chunky pile of deployable capital and everyone is asking the same question:

is this a ticking time bomb… or just a very large savings account with commitment issues?

This article is here to make dry powder feel less like a scary headline and more like what it actually is: a normal (if enormous) byproduct of how PE funds

raise money, call capital, buy companies, and eventually sell them. We’ll look at why the pile grew, what it does to dealmaking, why “more money” doesn’t

automatically mean “easy returns,” and how both GPs and LPs can think about dry powder without spiraling into doom-scrolling.

Key Takeaways (Because We’re All Busy)

- Dry powder is committed capital that hasn’t been invested yetreal money, but not sitting in one giant checking account.

- Big numbers can be misleading: global vs. buyout vs. U.S.-only totals aren’t interchangeable.

- High dry powder creates deployment pressure, which can push prices upbut it also fuels creativity (structure, secondaries, add-ons).

- The “problem” isn’t only too much cash. It’s cash + fewer exits + higher financing costs + valuation standoffs.

- Perspective matters: dry powder is a symptom of a long-cycle asset class navigating a short-cycle macro environment.

What “Dry Powder” Really Means (And What It Definitely Doesn’t)

Uncalled capital, not a vault of dollar bills

In private equity, investors (LPs) commit capital to a fund, and the fund manager (GP) calls that capital over time as it finds investments. Dry powder is

the portion of committed capital that hasn’t been called and put to work yet. Think of it like a dinner reservation: you said you’d show up, the table is

“yours,” but you haven’t ordered the steak.

Why headlines make it sound scarier than it is

When you see “trillions in dry powder,” it’s easy to imagine a single pile of cash burning a hole in someone’s pocket. In reality, dry powder is spread

across many funds, strategies, geographies, and vintage yearseach with different rules, timelines, and constraints. Some of it is earmarked for add-on

acquisitions. Some is for growth equity. Some is for buyouts. And some is committed to managers who won’t invest quickly even if you gently yell at them.

How Big Is the Pile? The (Important) Answer Is: “It Depends.”

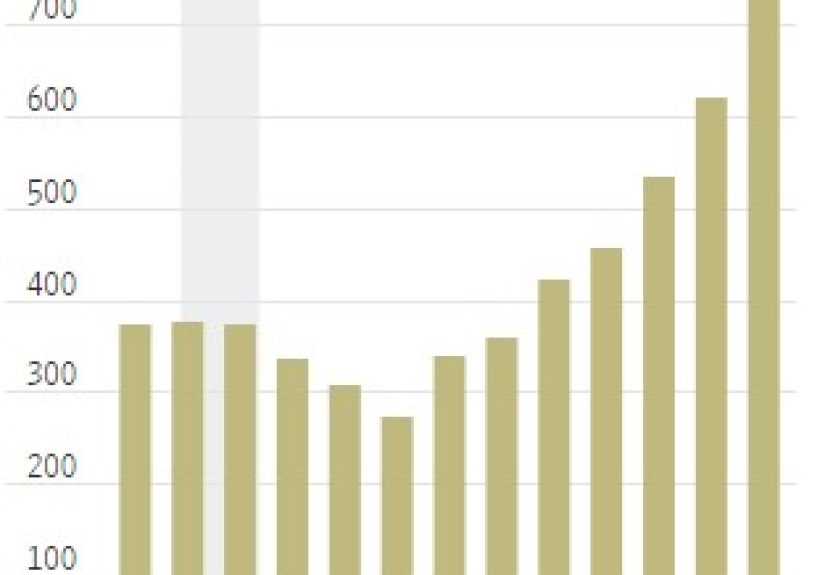

Dry powder totals vary depending on who’s counting and what they’re including. Some tallies focus on buyout funds only. Others include multiple private

market strategies. Some are global. Others are U.S.-specific. So instead of obsessing over a single number, it’s more helpful to understand the ranges and

what they imply.

Three ways the numbers get mixed up

- Scope: “Private equity” might mean buyout-only, or it might include growth, venture, and other strategies.

- Geography: Global totals can dwarf U.S. totals, but U.S. deal flow can still dominate certain years.

- Timing: Dry powder rises when fundraising outpaces investment and exits; it falls when deployment and distributions catch up.

Here’s the practical takeaway: whether the pile is described as “record U.S. buyout dry powder” or “global PE dry powder slightly off a peak,” the

underlying tension is similarlots of committed capital, not enough clean exits, and a market that’s picky about price.

Why Dry Powder Built Up: Four Forces, One Big Backlog

1) Fundraising didn’t stop just because dealmaking got awkward

For years, LPs poured money into private markets searching for return potential, diversification, and the promise of operational value creation. Even when

the public markets were wobbling, many investors still viewed PE as a long-horizon allocationmeaning commitments kept coming (especially to the biggest

brands), even as deployment slowed.

2) Financing got expensive, and leveraged buyouts are… kind of into leverage

Higher interest rates changed the math for buyouts: the cost of debt rose, underwriting got tighter, and lenders became choosier. That doesn’t kill deals,

but it slows them down, shrinks leverage, and makes sellers cling to yesterday’s valuations like they’re family heirlooms.

3) The valuation gap: buyers got rational, sellers got nostalgic

When capital is cheap, price negotiations can be a vibes-based exercise. When capital is expensive, buyers start caring about cash flow (rude). That creates

a gap between what sellers want and what sponsors can justifyespecially for businesses whose “growth story” is mostly “we grew during the stimulus years.”

4) Exits slowed, distributions dropped, and LPs started side-eyeing their capital calls

The PE flywheel works best when exits return cash to LPs, enabling new commitments without liquidity pain. When exit markets slow (fewer IPOs, fewer

strategic buyers paying up, slower sponsor-to-sponsor sales), distributions fall. LPs then get cautious, and fundraising can softenwhile dry powder remains

elevated because the money already raised still needs to be invested.

So Is Dry Powder “Bad”? Not Exactly. It’s Pressure. Pressure Can Be Useful.

Dry powder is like caffeine: a little sharpens focus; a lot makes you feel invincible right before you send an email you’ll regret. In PE, the “pressure”

shows up in several wayssome healthy, some not.

How dry powder can help markets

- Liquidity for sellers: When corporates or founders want out, PE capital can be a reliable buyer base.

- Stabilization in choppy cycles: Committed capital can keep deal activity alive when sentiment is weak.

- More options for growth and transformation: Sponsors can fund capex, tuck-ins, tech modernization, and operational upgrades.

How dry powder can hurt returns

- Higher entry multiples: More bidders chasing fewer “great” assets can lift prices.

- Shortcuts in diligence: Deployment pressure can tempt managers to move fast and “fix it later.”

- Style drift: Some funds stretch into unfamiliar sectors or structures to stay active.

The Real-World Impact on Deals: What Changes When Everyone Has Money?

1) Deal terms get more creative (translation: lawyers buy nicer boats)

When price is hard to agree on, structure steps in. Earnouts, preferred equity, seller notes, and other tools can bridge valuation gaps. You also see more

deals with minority stakes, staged capital, and partnership-style governanceespecially in sectors where founders want growth capital but not a full exit.

2) Add-on acquisitions become the main event

If platform deals are scarce or expensive, sponsors lean harder into buy-and-build strategies: acquire a solid core business, then use dry powder for tuck-in

acquisitions to grow revenue, improve margins, and (ideally) justify the original price. In a slower market, add-ons can be the quiet workhorse of

deployment.

3) Sponsor-to-sponsor deals stay relevant (even if everyone pretends they’re above it)

PE selling to PE is sometimes mocked as “hot potato with EBITDA.” But it’s also a practical solution when strategics are cautious and IPO windows are

narrow. Larger funds can buy assets from smaller funds, especially when the asset has scale potential, margin expansion levers, or global roll-up

opportunities.

4) Megadeals pop up when the math finally works

Big funds need big checks, and big checks often show up as take-privates and megadealsespecially when public markets misprice a company relative to what a

sponsor believes it can optimize over a longer holding period. These deals tend to cluster when financing becomes more available and boards get tired of the

quarterly earnings treadmill.

Zooming Out: Dry Powder Isn’t Just About Buying. It’s About Exiting, Too.

Continuation funds and secondaries: the “new exits” for a slower era

When a fund wants liquidity but the market won’t pay the price, managers increasingly use tools like continuation vehiclesselling an asset from an older

fund into a new structure, often backed by secondary investors. Done well, this can create optionality: partial liquidity for existing LPs, more runway for

value creation, and a controlled process instead of a forced sale.

The secondary market more broadly has become a pressure valve for the system. LPs can sell positions to generate liquidity; GPs can restructure ownership;

and the market can clear at discounts that reflect reality rather than wishful thinking.

NAV-based lending and other liquidity tools (useful, but not magic)

Funds also use net asset value (NAV) facilitiesborrowing against portfolio valueto create liquidity without selling assets immediately. This can help smooth

timing issues, but it’s not a free lunch. It introduces leverage at the fund level and works best when used thoughtfully and transparently.

Putting Dry Powder Into Perspective: Three Mental Models That Actually Help

Model 1: Dry powder is inventory management, not a moral failing

PE isn’t a day trader. A fund’s job is not “always be buying,” it’s “buy well.” Dry powder rises when managers refuse to overpay. That can be a feature,

not a bugassuming discipline doesn’t quietly morph into indecision.

Model 2: The “aging” of dry powder is the real signal

Fresh dry powder is normal. Older dry powder (capital sitting uninvested deeper into a fund’s life) is what raises eyebrows, because time constraints start

to matter. As capital ages, the risk of rushed deployment increasesand LP patience decreases.

Model 3: Dry powder is a competitive landscape indicator

High dry powder usually means competition is stiff for high-quality assets. In that environment, “just having money” isn’t advantage enough. The edge

shifts to origination networks, sector expertise, operational playbooks, and speed with discipline (yes, that’s a real thing).

What LPs Can Do About It (Besides Muttering “Vintage Year Risk” Into Their Coffee)

1) Re-check pacing and liquidity planning

If distributions are down and capital calls continue, liquidity modeling becomes non-negotiable. That doesn’t mean abandoning PE; it means avoiding

over-commitment and understanding how slower exits can compress cash flows across a portfolio.

2) Use secondaries strategically

Selling positions can be painful (discounts sting), but secondaries can also be proactive: rebalancing exposures, reducing concentration, and freeing up

capital for new opportunitiesespecially if you think upcoming vintages could be attractive.

3) Lean into selectivity

In a high-dry-powder era, the dispersion between top and mediocre managers can widen. For LPs, that’s a cue to focus on who can actually source,

underwrite, and operate through tougher cyclesrather than who can simply raise the next fund.

What GPs Can Do (Without Turning Deployment Into a Sport)

1) Stop treating financing like a footnote

In the cheap-money era, leverage could paper over a lot. In a higher-rate world, capital structure is part of the value creation plan. GPs that build strong

lender relationships, explore private credit options, and structure deals creatively can move faster without overpaying.

2) Make operational value creation the headline again

When multiple expansion is harder, fundamentals matter more: pricing strategy, sales productivity, procurement, tech modernization, working capital, and

margin discipline. If you’re sitting on dry powder, the best “deal” might be buying a good business at a fair price and improving it like you mean it.

3) Use add-ons with intent

Buy-and-build works when the strategy is coherent: clear synergies, integration capabilities, and a thesis beyond “we can make the org chart bigger.” Dry

powder helps fund add-ons, but integration is what turns them into real value.

4) Create liquidity deliberately

Partial exits, sponsor-to-sponsor sales, continuation vehicles, and structured solutions can all help address the distribution drought. The trick is to use

them to maximize long-term valuenot merely to create the appearance of activity.

Where This Might Go Next

The market doesn’t need dry powder to disappear. It needs the PE flywheel to spin more smoothly: a healthier exit environment, financing conditions that

support transactions without fantasy math, and enough confidence for buyers and sellers to agree on reality.

If interest rates stabilize or ease and IPO and M&A windows open wider, deployment can accelerate. But even without a “perfect” macro backdrop, dry powder

will keep flowing into dealsbecause committed capital has a job to do, and the best managers don’t wait for ideal weather to build value.

Field Notes: What Dry Powder Pressure Feels Like (500-ish Words of “Experience,” Minus the Mythology)

Let’s make this human. Dry powder isn’t just a chart in a glossy reportit’s a vibe that shows up in meetings, term sheets, and the subtle facial twitch of

a partner who realizes it’s September and the fund’s investment period clock is not, in fact, a suggestion.

Picture an investment committee call. The deal team is presenting a business that’s “mission-critical,” “category-defining,” andthis is the tell“not

expensive when you think about it.” Someone asks what happens if revenue growth slows. Another person asks whether the add-on pipeline is real or just a

spreadsheet with ambition. Then comes the quiet question that always lands: “How many other bidders?” If the answer is “a lot,” you can feel the room

recalibrate. Dry powder creates a world where everyone is well-funded, so the differentiation isn’t cashit’s conviction backed by proof.

Now jump to the seller side. A founder hears “private equity” and imagines two things: (1) a big number, and (2) someone turning the office into a

KPI-themed escape room. When dry powder is plentiful, founders know there are multiple sponsor options, so they negotiate more than price. They ask about

control, governance, brand, leadership continuity, and whether the buyer will actually invest in growth or just “optimize” until the building starts filing

HR complaints.

In the middle market, deployment pressure has a funny effect: it turns “nice-to-have” into “strategic imperative.” A business that would have been a

passing glance three years ago suddenly becomes a serious targetbecause it’s stable, has real cash flow, and can be a platform for add-ons. That’s not

inherently bad. But it does mean the diligence process needs to be honest. In a high dry-powder environment, the temptation is to underwrite the upside and

outsource the downside to “future operational improvements.” Translation: “We will fix it with vibes and a new CRM.”

Then there’s the exit sidewhere dry powder meets the distribution drought. When a GP tries to sell an asset and strategic buyers hesitate, the conversation

shifts quickly to alternatives. Do we run a broader sponsor process? Do we carve out a piece? Do we recap? Do we explore a continuation fund? None of those

options are “easy,” but they’re part of the modern PE toolkit. The experience, for LPs, is often a mix of patience and plot twists: you’re waiting for cash

distributions, and instead you get a well-produced update deck explaining why the business is “poised for the next chapter” and why “optional liquidity

pathways” are being evaluated. (Optional pathways is consultant-speak for “the market is being annoying.”)

The biggest practical lesson that emerges from all these scenarios is simple: in a world with lots of private equity dry powder, execution matters more than

ever. The winners aren’t the firms that sprint to deploy. They’re the ones that can source differentiated deals, structure them intelligently, improve the

business for real, and create liquidity without relying on a magical return of 2021 pricing.

Conclusion

Private equity dry powder sounds dramatic because the numbers are dramatic. But the existence of a large capital overhang isn’t automatically a crisisit’s a

signal. It signals how much capital investors have committed to private markets, how selective GPs have been during a tougher cycle, and how strongly exits

influence the system’s rhythm.

The healthiest way to “put it into perspective” is to treat dry powder as a pressure gauge, not a scoreboard. If the pile is aging, if exits remain stuck,

and if deployment turns frantic, risks rise. If capital is deployed with discipline, supported by credible value creation and realistic financing, dry powder

becomes what it was always meant to be: future ownership in real businesses, not a scary headline.