Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What sparked the controversy?

- A quick timeline of the blowup

- What does Rebel Wilson say happened?

- Sacha Baron Cohen’s clap back: what his camp says

- Why some editions reportedly removed or blacked out parts

- How this played out in the court of public opinion

- What the dispute says about Hollywood set boundaries

- FAQ: the questions people keep asking

- Conclusion

Celebrity memoirs are supposed to be a little bit confessional, a little bit inspirational, andlet’s be honesta little bit “wait, she said what?”

But when a memoir chapter turns into a public back-and-forth between two famous actors, it stops being harmless tea and starts touching on bigger questions:

how Hollywood handles boundaries, how “comedy” gets used as cover, and what happens when the receipts (or alleged receipts) come out.

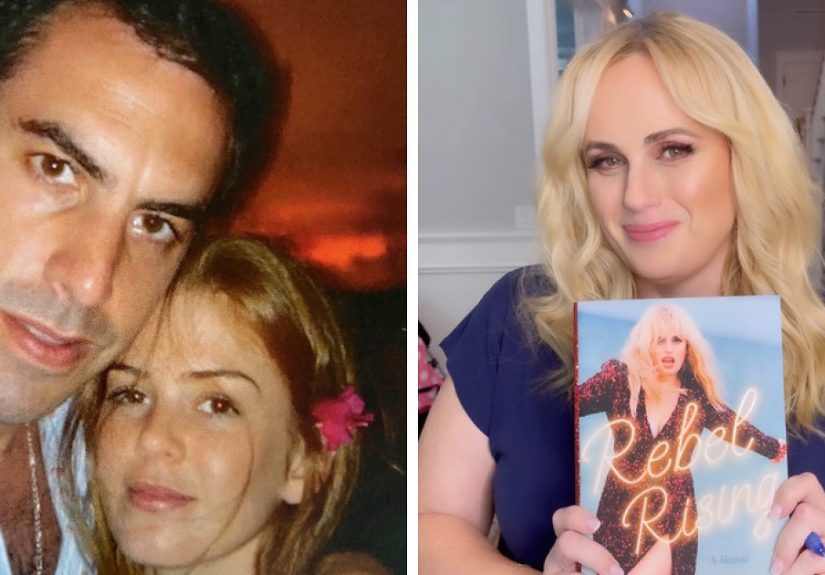

That’s exactly what happened when Rebel Wilson’s memoir stirred up headlines for a chapter about an unnamed “massive a–hole,” and she later identified

Sacha Baron Cohen as the person she meant. Almost immediately, Cohen’s camp pushed back hard, calling the claims false and saying they were contradicted by

detailed evidence and witness accounts. The disputerooted in their time working on a raunchy 2016 comedythen spilled into publishing decisions,

including reported redactions in some international editions.

Below is a clear, up-to-date breakdown of what’s been reported, what each side says, and why this story landed so loudly. (Spoiler: it’s not just because

the word “a–hole” is search-engine catnip.)

What sparked the controversy?

In the run-up to her memoir Rebel Rising, Wilson teased that she had written about a difficult Hollywood experience involving a “massive a–hole,”

and she suggested she was facing legal and PR pressure around the chapter. She later identified the person as Sacha Baron Cohen and framed her decision as

refusing to be intimidated.

From there, the story moved fast: public posts, headlines, excerpts, statements from representatives, andeventuallypublishing complications in certain

markets. In modern celebrity culture, that’s basically the full bingo card.

A quick timeline of the blowup

- 2013–2016: Wilson and Cohen connect professionally and later work together on The Brothers Grimsby, a very R-rated comedy.

- 2014 (earlier comments resurface): Prior public remarks attributed to Wilson about being pressured into nudity become part of the wider conversation.

- Late March 2024: Wilson publicly identifies Cohen as the subject of the memoir chapter, using the phrase “a–hole.”

- Immediately after: Cohen’s representative denies the allegations and says they are contradicted by documents, footage, and eyewitness accounts.

- Early April 2024: The memoir releases in the U.S., while reports swirl about delays and/or redactions in some other editions.

- Later April 2024: Reporting indicates at least one international edition contains redactions tied to legal concerns, and Cohen’s team frames that as a “victory.”

What does Rebel Wilson say happened?

In reporting based on excerpts from Rebel Rising, Wilson describes her experience working with Cohen on the set of

The Brothers Grimsby as uncomfortable and boundary-pushing. She alleges repeated pressure to appear nude despite her saying she doesn’t do nudity.

She also recounts a specific incident during filming in Cape Town involving an additional scene she says she was summoned to shoot, where she alleges Cohen

made an explicit request that wasn’t in the script. Wilson describes feeling scared and trying to exit the situation, and she claims she improvised a less

explicit alternative in the moment.

She also presents her motivation as speaking about an experience she believes shouldn’t be normalizedespecially when comedic shock value is involved.

In other words: she’s not just describing an awkward day at work, she’s describing what she believes was a power dynamic.

The “comedy” factor

The tricky part about disputes like this is that they often sit at the intersection of two truths:

raunchy comedies frequently push boundaries by design, and people can still feel pressured or humiliated even when a production labels something a “joke.”

That’s why this story got traction beyond celebrity gossipit taps into the ongoing industry shift toward clearer consent and clearer protocols on set.

Sacha Baron Cohen’s clap back: what his camp says

Cohen’s responsevia a representativewas a full-throated denial. The statement describes Wilson’s allegations as “demonstrably false” and says they are

contradicted by “extensive detailed evidence,” including contemporaneous documents, film footage, and eyewitness accounts from people present around the

production.

In other words, this wasn’t a soft “we disagree” or a vague “that’s not how I remember it.” This was the PR equivalent of slamming a binder onto the table.

The message: not only are these claims denied, but the denial comes with backup.

The “evidence” strategy (and why it matters)

When a public figure responds to allegations with the phrase “we have evidence,” it usually signals two things:

- Legal posture: The response is crafted with defamation risk in mind, not just reputation management.

- Public persuasion: The goal is to influence how the audience frames the storyless “he said/she said,” more “there’s proof.”

Even without the public seeing every piece of documentation, the claim of evidence changes the temperature. It encourages readers to treat the dispute like

a factual contestnot a feelings-based conflict.

Why some editions reportedly removed or blacked out parts

Here’s where publishing gets interesting (yes, I’m seriouspublishing can be messy in the most dramatic way).

Reports indicated that certain non-U.S. editions of Wilson’s memoir did not include the chapter in full, with parts appearing blacked out or redacted,

and statements from publishers pointing to legal reasons.

That doesn’t automatically prove one side “won” on the facts. It does, however, show how risk-averse publishing becomes when claims could trigger legal action

in jurisdictions with different defamation standards and litigation realities than the United States.

Different markets, different legal headaches

In the U.S., publishers often rely on a mix of legal review, fact-checking, sourcing, and insurance. In other countries, defamation frameworks and litigation

incentives can be very differentmaking publishers more likely to redact disputed passages, delay releases, or require edits.

The result is a weird modern phenomenon: the same celebrity memoir can exist in multiple “legal versions,” like a director’s cut nobody asked for.

How this played out in the court of public opinion

The public reaction split into familiar camps:

some people viewed Wilson’s comments as an overdue account of a harmful work environment,

while others focused on Cohen’s denial and the idea that controversial claims should be backed by verifiable proof.

Add in social media’s love of a villain narrative, and the whole thing got amplified fast.

Memoir marketing meets moral questions

Memoirs are marketed on “truth,” but they’re also sold on drama. When a memoir includes allegations about a specific personespecially a famous onepublishers

and publicists have to thread a needle:

- Promote the book without turning it into a defamation grenade.

- Respect personal storytelling without treating unverified claims like confirmed fact.

- Let the author speak while minimizing legal exposure.

That tension is why stories like this often generate additional headlines about the book itselfdelays, redactions, “lawyered up” statementsbecause

the publishing process becomes part of the spectacle.

What the dispute says about Hollywood set boundaries

Whether you believe Wilson’s account, Cohen’s denial, or some third explanation that only the people on set truly know, the broader context is hard to ignore:

entertainment has changed. What was once dismissed as “that’s just how comedy is” is now being filtered through a culture more attentive to consent, workplace

professionalism, and power dynamics.

The rise of intimacy coordination and “closed set” practices

In the last decade, productions have increasingly formalized how intimate or explicit scenes are handledwho is present, what is agreed in advance, and how

last-minute “improvisation” is managed. This doesn’t eliminate disputes, but it raises expectations:

if something changes on the day, it should be renegotiated clearly, with the performer’s explicit consent.

That’s part of why stories about older productions can land differently today. The audience hears them through a 2020s lens, not a “2010s shock-comedy” lens.

FAQ: the questions people keep asking

What memoir is this about?

Wilson’s memoir is titled Rebel Rising, and the controversy centers on a chapter describing her experience working with Cohen on a film set.

What film connects them?

They worked together on The Brothers Grimsby, a 2016 R-rated comedy that also features

in a major role and includes in the cast.

Did Cohen respond directly?

Reporting widely described a response issued through a representative, strongly denying the allegations and citing supposed evidence and eyewitness accounts.

Why would any edition be redacted?

Publishers sometimes redact disputed claims for legal reasons in certain markets, especially when defamation standards, litigation risk, or insurance factors

differ from the U.S. context.

Conclusion

The headline version of this story is simple: Rebel Wilson wrote a chapter describing a bad experience, called Sacha Baron Cohen an “a–hole,” and Cohen’s camp

clapped back with a denial and claims of evidence. The real story is messier: it’s about how entertainment culture is changing, how memoirs collide with legal

reality, and how “it’s just a joke” doesn’t always land the same way for everyone involved.

If nothing else, this controversy is a reminder that modern celebrity narratives don’t live only in books or on screens. They live in public statements,

in publication decisions, and in the way audiences re-litigate old sets through new expectations.

500-word add-on: experiences people describe when a set turns into a boundary negotiation

When stories like this hit the news, a lot of people imagine film sets as either glamorous playgrounds or chaotic circus tents. The truth, according to many

actors and crew members who speak about set dynamics in interviews and industry discussions, is usually more mundaneand that’s what makes boundary problems

harder to spot in the moment. The day starts with a call time, a wardrobe rack, a lighting adjustment, a dozen tiny decisions. Then, sometimes, a “small”

request shows up that isn’t small at all.

One common experience performers describe is the surprise pivot: you arrive thinking you’re shooting Scene A, but someone says, “We’re also going to grab a

quick extra beat.” The phrase “quick extra beat” can be harmlessan extra reaction shot, a line tweak, a physical gag. But it can also create pressure,

especially when the set is moving fast and everyone is watching the clock. People don’t always want to be the person who “slows things down,” which is why

clear protocols matter more than anyone’s ability to be assertive on the spot.

Another experience is the laughter shield. On comedy sets in particular, performers have described how discomfort can get wrapped in jokes. If a moment is

framed as “we’re just being edgy,” it becomes socially harder to say, “I’m not okay with that.” Not because the person lacks boundaries, but because the room

is signaling that boundaries are uncool. That’s where power dynamics sneak in: the higher-status person can keep the joke going; the lower-status person has

to decide whether to risk being labeled “difficult.”

Then there’s the documentation problem. A performer may remember a moment as improvised pressure; a production may remember it as a scheduled scene with prior

approval. Both sides can point to different “truth anchors”: memory, emails, script pages, call sheets, video, witnesses. That’s why many productions now

emphasize written confirmations for nudity riders, intimate choreography plans, closed-set rules, and consent check-insso no one has to rely on vibes when a

dispute arises.

Finally, there’s the aftershock experience: how people cope once the day is over. Some describe laughing it off because that’s what keeps you employed.

Others describe calling an agent, texting a friend, or mentally bargaining: “Just get through today.” Years later, that same person might reframe the moment

with more clarity, or with more anger, especially after cultural conversations evolve. That doesn’t automatically validate every claim in every memoirbut it

does explain why stories can surface long after a film wraps.

The healthiest takeaway isn’t “never do comedy” or “never improvise.” It’s simpler: if a scene involves intimacy, nudity, or explicit physicality, the plan

should be specific, agreed in advance, and easy to pause without punishment. When productions make consent boring and procedural, they make controversy far less

likelyand they protect everyone, including the story itself.