Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Exactly Is Human Echolocation?

- The Science Behind a “Sixth Sense”

- How Humans Echolocate: Clicks, Canes, and Everyday Sounds

- Who Benefits Most from This Sixth Sense?

- Limitations: We Won’t Become Bats Overnight

- Future Possibilities: Tech and Training for a New Sense

- What Learning Echolocation Feels Like: Experiences and Practical Insights

- Conclusion: A Realistic Sixth Sense, Backed by Science

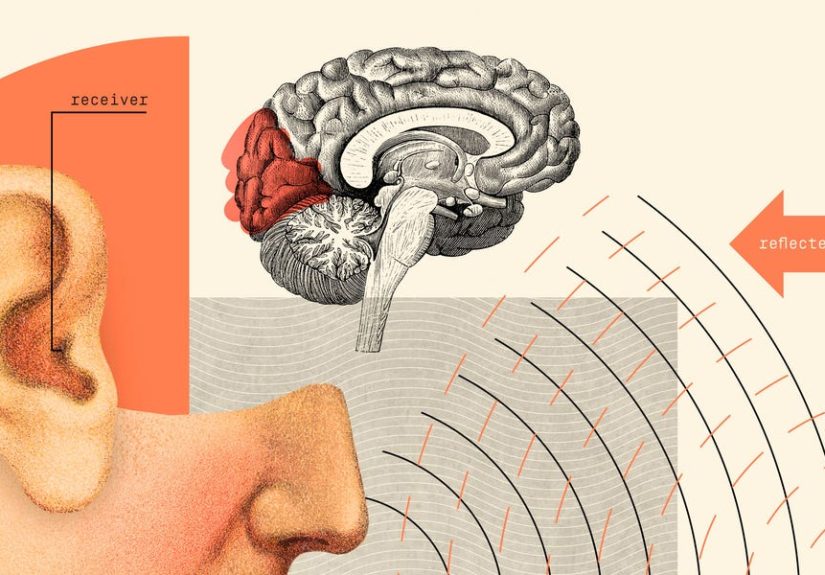

Bats do it. Dolphins do it. And now, scientists say humans can do it too no wings, no flippers required.

Thanks to a growing body of research on human echolocation, we now know that people can learn to “see” with

sound, navigating and recognizing objects using nothing but mouth clicks and echoes. It’s not a comic-book

superpower, but it’s surprisingly close to a real sixth sense.

In the past decade, researchers have shown that both blind and sighted volunteers can learn echolocation

with targeted training. Their brains even reorganize so that echoes begin to activate areas usually reserved

for vision. The result is a practical, science-backed way for humans to expand how we sense the world

especially for people with visual impairments, but potentially for anyone who wants to sharpen their spatial awareness.

What Exactly Is Human Echolocation?

Human echolocation is the ability to detect objects and spaces by listening to the echoes of sounds you

produce yourself. Instead of using ultrasound like bats, humans use regular audible sounds most commonly

tongue clicks, cane taps, finger snaps, or gentle footfalls on the ground.

When a sound wave leaves your mouth and hits something a wall, a doorway, a parked car, a tree it bounces

back with slightly different timing and loudness. With practice, your brain can decode those subtle changes to

figure out:

- Where an object is (left, right, near, far, high, low)

- How big it is (narrow doorway vs. wide open hall)

- What shape it has (flat wall vs. protruding column or pole)

- How solid it might be (dense brick vs. soft foliage)

Skilled echolocators can use this information to walk around unfamiliar spaces, avoid obstacles, locate doorways,

follow paths, and even identify larger shapes such as parked vehicles or trees. Some blind echolocation experts

have been documented hiking, cycling, or playing sports using this kind of acoustic “vision.”

The Science Behind a “Sixth Sense”

Training the Brain to Hear with “Vision” Circuits

One of the most striking discoveries about human echolocation comes from brain imaging studies. When researchers

scan the brains of blind expert echolocators listening to echoes, they don’t just see activity in traditional

hearing centers. They also see strong activation in the visual cortex the same part of the brain sighted

people use to process images.

In other words, the brain is repurposing its visual machinery to interpret sound. That’s a textbook example of

neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire itself. For blind individuals, this re-wiring seems

especially robust, but studies show that sighted people also show measurable changes in similar brain areas after

echolocation training.

How Fast Can Humans Learn Echolocation?

If echolocation sounds like something that would take years to master, scientists have good news. Controlled

training studies have found that both blind and sighted adults including older adults can show meaningful

improvements in echolocation over just a few weeks.

In a landmark training program, volunteers practiced tongue-click echolocation for around 10 weeks, combining

computer-based tasks with real-world navigation exercises. By the end of the program, both blind and sighted

participants could:

- Detect objects they couldn’t see

- Judge the distance and relative size of obstacles

- Navigate simple mazes and hallway turns using echoes alone

Many blind participants reported concrete improvements in daily life walking more confidently on streets,

locating doorways, or moving around crowded spaces with less anxiety. Not everyone turned into a “human bat,”

but the gains were practical and measurable.

How Humans Echolocate: Clicks, Canes, and Everyday Sounds

The Classic Tongue Click

The most famous style of human echolocation uses a sharp tongue click sort of like popping your tongue off

the roof of your mouth. It’s:

- Short and crisp, so echoes are easier to distinguish

- Directionally flexible, because you can point your head where you want to “scan”

- Always available no gadgets required

Different surfaces reflect different sounding echoes. A brick wall might sound hard and loud, while a curtain

or hedge sounds softer and more muted. Over time, the brain learns to treat these tiny differences like a

kind of “sound texture map” of the environment.

Other Sound Sources That Work

Tongue clicks aren’t the only option. Research has looked at how different sound types change the quality of

echolocation. Cane taps, finger snaps, or even small handheld buzzers can send out useful pulses of sound. The

ideal sound tends to be:

- Brief, not drawn-out (so echoes don’t smear together)

- Distinct from background noise

- Loud enough to bounce back, but not painfully loud

Some people with visual impairments already exploit these natural cues without calling it “echolocation.” They

notice how the sound of their footsteps changes in a narrow hallway versus an open courtyard, or how voices

echo differently near a wall. Formal echolocation training teaches people to recognize and deliberately use

those cues.

Who Benefits Most from This Sixth Sense?

People with Visual Impairments

For blind and low-vision individuals, echolocation can be a powerful addition to tools like white canes and

guide dogs. It doesn’t replace them, but it adds another layer of information. For example:

- Detecting overhead obstacles that a cane might miss

- Noticing gaps like open doorways or archways at a distance

- Feeling the shape of a space tight corridor vs. open room before entering

Some orientation and mobility specialists now incorporate basic echolocation concepts into training, helping

clients experiment with sound and echo cues in safe environments.

Could Sighted People Use Echolocation Too?

Yes and many already do, without realizing it. Studies show that sighted people can learn to discriminate

between different object shapes and positions using echoes, especially after structured practice. Unlike blind

participants, sighted people often rely less on echolocation in everyday life because vision dominates their

attention. But for specific activities, an “audio radar” can still be useful:

- Moving safely in low-light or smoky environments

- Exploring caves or dark industrial spaces

- Supporting search-and-rescue tasks alongside devices and flashlights

For now, echolocation remains a niche skill for sighted people, but the research clearly supports the idea that

this sixth sense is available to almost anyone who’s willing to train it.

Limitations: We Won’t Become Bats Overnight

Before we crown ourselves honorary bats, it’s important to understand the limits of human echolocation.

- We use audible sound, not ultrasound. That means our resolution is lower and our range is shorter than bat sonar.

- Background noise matters. Busy streets, loud music, or echoey rooms can make it harder to pick out useful echoes.

- It takes focused attention. Early learners often find echolocation mentally tiring. Over time, it can become more automatic, but practice is essential.

- Social stigma is real. Some people worry that tongue clicks in public will draw unwanted attention or be misunderstood, which can discourage consistent use.

Even with these limits, scientists emphasize that echolocation is still remarkably useful as a supplemental sense.

It’s less like turning into a superhero and more like acquiring a very refined version of a skill you already have.

Future Possibilities: Tech and Training for a New Sense

As evidence for human echolocation mounts, researchers and engineers are starting to imagine what comes next.

Some areas of active and potential development include:

- Specialized training programs that combine virtual environments, audio simulations, and real-world navigation to help people learn faster.

- Wearable echolocation devices that emit optimized sounds and provide clearer, more consistent echoes.

- Augmented reality for sound, where audio cues are layered onto the environment to guide people through buildings or transit hubs.

In the long run, we may see echolocation blended with other assistive technologies like smart canes, GPS apps,

and indoor navigation systems to create a rich multisensory map of the world for anyone who needs or wants it.

What Learning Echolocation Feels Like: Experiences and Practical Insights

Reading about echolocation in a research paper is one thing; trying it yourself is another. While everyone’s

experience is unique, people who participate in training programs tend to describe a surprisingly similar journey

as their “sound sense” develops.

Week 1–2: “I Just Hear Clicks”

At the beginning, most people report that all they notice is the sound of their own tongue clicking not exactly

life-changing. In a quiet room, instructors might start with simple tasks, like distinguishing a big board placed

in front of the learner versus an open space. The learner stands in one spot, clicks a few times, and guesses

whether the board is there.

At first, this feels like random guessing. But as sessions continue, learners begin to notice tiny differences: a

slightly “fuller” sound when the board is there, a more “hollow” quality when space is open. These differences are

subtle but real, and once your brain knows what to listen for, they’re hard to un-hear.

Week 3–6: Shapes, Corners, and Doorways

As training progresses, tasks become more complex. Instead of just “board or no board,” learners might be asked to

tell the difference between a flat surface and a pole, or between a narrow doorway and a wide opening. They may walk

slowly down a hallway, using clicks to find intersecting corridors or doorframes.

Many people describe this stage as the moment echolocation stops feeling like “guessing” and starts feeling like a

genuine sense. Doorways begin to stand out as gaps in an otherwise solid wall of echo. Corners feel like sudden changes

in the way sound bounces back. With repetition, these patterns form an intuitive sound-based map in the mind.

Week 7–10: Moving Through the World with Sound

In the later stages of a typical 10-week program, learners move into real-world environments: courtyards, stairwells,

parks, or quiet streets. They may walk routes first with visual information or a guide, and then repeat them with more

reliance on echoes and cane feedback.

One common report from blind participants is a boost in confidence. Instead of feeling like they’re reacting only to

what their cane hits, they begin to sense obstacles or openings a bit earlier, giving them time to adjust their path

smoothly. Even small changes like recognizing an overhanging branch before it brushes their face can feel like big

wins.

Emotional and Social Layers

The emotional side of learning echolocation is just as important as the technical side. Many learners say they feel

empowered and curious almost like rediscovering their environment from scratch. At the same time, there can be

self-consciousness: clicking your tongue in public isn’t exactly standard behavior.

Instructors often encourage learners to treat echolocation as a personal tool rather than a performance. Some use

quieter clicks in crowded spaces, or lean more on cane taps and footsteps, which draw less attention. Over time,

many become more comfortable using echolocation openly, especially once they experience how much safer and more in

control they feel.

Using Echolocation in Everyday Life

For people who stick with it, echolocation can become a background skill something that runs quietly in the

mind without constant effort. Examples of everyday uses include:

- Finding a hallway entrance in a noisy building by clicking and listening for the “hole” in the echoes

- Noticing when you’ve walked from a narrow space into a large lobby or atrium

- Detecting parked cars or big obstacles on a sidewalk before reaching them

Sighted practitioners may not rely on echolocation all day long, but they can find it helpful in dimly lit spaces,

during power outages, or in unfamiliar basements and corridors. For blind practitioners, it can evolve into a core

navigation tool that complements their cane or guide dog.

Ultimately, the experience of learning echolocation is less about turning into a superhero and more about discovering

how flexible and adaptable the human brain really is. With a bit of training, sound stops being just “noise” and

starts carrying rich, structured information about the world around us a genuine sixth sense hiding in plain (or

rather, audible) sight.

Conclusion: A Realistic Sixth Sense, Backed by Science

Scientists have now shown that humans can develop a functional sixth sense through echolocation. With weeks of

structured practice, people can learn to read echoes, navigate spaces, and even recruit visual areas of the brain to

process sound. It’s not magic and it won’t replace vision, but it can genuinely expand how we perceive and move

through the world.

Whether you’re a researcher, a person with low vision looking for more independence, or just someone fascinated by

the hidden talents of the human brain, echolocation offers a compelling message: our senses are not fixed. With the

right training, our brains are capable of much more than we usually ask of them.