Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Who Is Kathy Kleiner Rubin (and Why Her Voice Hits Different)

- The Night at Chi Omega: A Timeline That Still Doesn’t Feel Real

- Surviving the Immediate Aftermath: Shock Does Weird Things

- Recovery: The Long Middle Chapter Nobody Glamourizes

- Facing Bundy: Testimony, Pressure, and Taking the Story Back

- Debunking the “Charming Monster” Myth (Spoiler: It’s Marketing)

- Why Kathy Speaks Out Now

- How to Talk About Chi Omegaand True CrimeWithout Losing the Plot

- Conclusion: The Point Isn’t BundyIt’s Kathy

- Extra: 10 Survivor-Style “Life After” Experiences (500+ Words of Real-World Takeaways)

- 1) Your brain may protect you with weird rewrites

- 2) Healing is mostly inconvenient

- 3) Anger is a normal stage, not a personality flaw

- 4) “Safety rituals” aren’t sillythey’re coping

- 5) Triggers can be random and rude

- 6) People will say the wrong thingoften trying to be nice

- 7) Your identity can feel “split” for a while

- 8) Telling your story can be healingor exhaustingor both

- 9) True crime can be validating, but it can also re-open wounds

- 10) Recovery is not a straight lineand that’s still success

Some stories get told so often they start to sound like folkloreuntil you remember they happened to a real person

with a real face, a real family, and a real life that had to continue on Monday morning.

Kathy Kleiner Rubin’s story isn’t a “true crime moment.” It’s a survival storymessy, expensive (hello, medical bills),

emotionally complicated, and ultimately, deeply human. And yes, there are details from the night Ted Bundy attacked

the Chi Omega house at Florida State University in January 1978. But the part most people skip is the bigger, tougher

chapter: what Kathy did after the headlines moved on.

Who Is Kathy Kleiner Rubin (and Why Her Voice Hits Different)

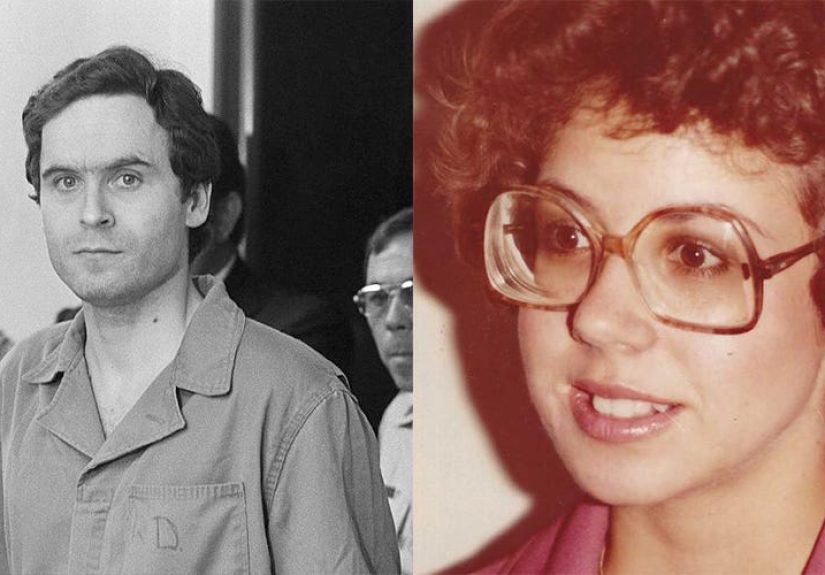

In the public imagination, Ted Bundy is often packaged as a dark celebrity: courtroom cameras, a smug smirk, and a

thousand documentaries that somehow find time for his “charm” but not for the women he harmed. Kathy Kleiner Rubin

pushes back on thathard.

She’s not speaking from speculation or “internet research.” She’s speaking as someone who was living her everyday

college lifeclasses, friends, dorm-room chaosuntil a violent intrusion changed her body and her nervous system in

minutes. Decades later, she’s spoken publicly, co-authored a memoir (A Light in the Dark), and made a point of

pulling the spotlight off Bundy and back onto victims and survivors.

That’s the key: Kathy doesn’t sell fear. She sells truthand insists that survivors aren’t supporting characters in a

killer’s “origin story.” They’re the whole point.

The Night at Chi Omega: A Timeline That Still Doesn’t Feel Real

A campus that felt safeuntil it wasn’t

In early 1978, Florida State University felt, to many students, like the kind of place where you could walk around at

odd hours and mostly assume you’d make it home. People were out late. Doors got propped. Life was social and loud and

normaluntil it wasn’t.

How the intruder got in

The Chi Omega sorority house became vulnerable in the most painfully ordinary way: a faulty lock. There wasn’t a movie-villain

level “master plan” required to exploit it. An intruder slipped in through a door that didn’t properly secure, carrying a heavy

piece of firewoodbasically the world’s worst DIY tool.

If you feel the sudden urge to check your own locks right now, congratulations: your nervous system is working as designed.

Kathy’s story has that effect.

The moment Kathy woke up

Kathy has described waking to the sound of her bedroom door opening and something being knocked over between the beds.

In the dark, she could make out a silhouetteclose enough to feel immediate danger, but not close enough to process it like a

rational, daytime event. That’s the thing about sudden violence: your brain doesn’t say, “Interesting, let’s analyze.”

It says, “Survive.”

She was struck in the face and suffered severe injuries. It’s hard to type that sentence without wanting to apologize for it,

because it reads too clean for what it actually meant: shattered bone, pain that escalated fast, shock that scrambled reality,

and a body trying to keep breathing anyway.

Why a pair of headlights changed everything

One of the most haunting details in Kathy’s account is also one of the most mundane: a car pulling into a parking lot.

Headlights swung across the window and lit up the room. The intruderspooked, suddenly exposedmoved erratically and fled.

There’s a strange unfairness to this. Survival can hinge on dumb luck: a late return, a light beam, a single timing shift.

It’s not “destiny.” It’s physics, coincidence, and a survivor who still has to live with the aftermath regardless.

Surviving the Immediate Aftermath: Shock Does Weird Things

When responders arrived, Kathy’s injuries were obvious and alarming. But the mind’s reaction can be just as dramatic.

Kathy has described being carried out on a stretcher amid flashing emergency lights and radio chatter and, in that moment,

interpreting the scene like a carnivalher brain reaching for something familiar when reality was too big to hold.

That detail matters because it’s a reminder that trauma isn’t only what happens to the body. It’s what happens to perception,

memory, and the way your brain tries to protect you by temporarily rewriting the world.

Meanwhile, two sorority sisters were killed in the same attack, and another young woman nearby was assaulted shortly after.

The scale of that night is part of why the story still echoes: it wasn’t a single event. It was a burst of violence that expanded

outward in minutes.

Recovery: The Long Middle Chapter Nobody Glamourizes

Physical healing: slow, painful, and relentlessly practical

The physical recovery was not a montage. It involved surgeries, dental and jaw repair, and the grueling logistics of eating,

sleeping, speaking, and simply existing while injured. Kathy has described the experience of being cared for at home, including

the reality of trying to eat when your jaw has been repaired and immobilizedpureed foods, careful routines, and the deep boredom

that comes with healing slowly.

She was brought back to her family for recovery, away from campus. That separation is its own kind of loss: you don’t just heal

from injuries; you heal from being pulled out of your life and dropped into a different one.

Emotional healing: anger, grief, and “baby steps” that actually count

Kathy has spoken about angeranger that it happened, anger at what it stole, anger that she had to leave friends and familiarity.

And then sadness: the kind that shows up when the adrenaline fades and you realize your “before” life isn’t coming back exactly

as it was.

Recovery, in her telling, wasn’t about becoming fearless. It was about becoming functional again. It was choosing life in tiny

decisions: going out, creating routines, and eventually building a future that wasn’t organized around Bundy’s shadow.

Facing Bundy: Testimony, Pressure, and Taking the Story Back

Later came depositions and court appearancesanother kind of ordeal. Kathy has described being in the same room as Bundy,

feeling intimidated but committed to helping prevent further harm. Courtrooms have a way of turning human suffering into evidence

and procedure, and that can feel like a second violation.

At trial, survivors faced aggressive questioning. Kathy has recalled defense tactics that implied blame where none belonged

the old “maybe she wanted it” nonsense that should’ve been buried decades ago but still crawls out of the ground in too many cases.

In July 1979, Bundy was convicted for the Chi Omega murders and associated attacks. Evidence presented included eyewitness testimony

and forensic comparisons discussed in court records and coverage. Kathy’s role wasn’t to “perform trauma” for the publicit was to

speak truth in a system that demands it in a very specific, often exhausting way.

Debunking the “Charming Monster” Myth (Spoiler: It’s Marketing)

Kathy Kleiner Rubin has been blunt about how Bundy has been framed over the years. The popular narrative loves the “handsome, brilliant

law student” angle. It makes for compelling TV. It also quietly turns a predator into a brand.

But survivors and careful reporting point to something less cinematic and more accurate: Bundy often relied on surprise, deception,

and attacking people who were alone or asleep. That’s not mastermind behavior; that’s coward behavior.

Another uncomfortable truth: the “Bundy mystique” sometimes grows because it flatters everyone else. It lets media sell the story,

lets audiences feel safely horrified, and lets institutions explain failures as “Well, he was just too smart.” Kathy and her co-author

have challenged that framing, arguing that it gives him credit he didn’t earn and steals attention from the victims who deserved the

world’s focus.

One useful litmus test: if a story makes you remember Bundy’s smirk but not the victims’ dreams, it’s not journalismit’s merchandising.

Why Kathy Speaks Out Now

Kathy’s public presence isn’t about reliving the attack for entertainment. It’s about controlling the narrative, honoring the women who

were killed, and offering perspective on what survival actually demands over decades.

She has shared how she protected her son from being consumed by the story, even while being honest that something terrible happened.

That balancing acttruth without obsessionis a skill survivors learn the hard way.

She also frames her life as more than one night. She has spoken openly about other health battles and the reality that survival is

sometimes a recurring job, not a single moment. The point isn’t “look what happened to me.” The point is “look what I built anyway.”

How to Talk About Chi Omegaand True CrimeWithout Losing the Plot

1) Put victims and survivors in the center

Kathy has criticized how victims’ names are often reduced to a quick listlike commas in the margin of a killer’s biography. A better

approach is harder, but worth it: treat victims as whole people. Who were they? What did they want? What did they love? A case should

never erase the humanity it harmed.

2) Be careful with “fascination”

True crime can educate and even help people recognize red flags and support reforms. It can also drift into fandomquotes on T-shirts,

memes, and “hot takes” that flatten real suffering into content. If the tone feels like entertainment first and human beings second,

it’s time to step back.

3) Remember the practical lessons

The Chi Omega attack is often discussed as an infamous moment in serial killer history. But it’s also a lesson in everyday vulnerability:

broken locks, assumptions of safety, and the fact that violence often exploits the ordinary. The preventive takeaway isn’t paranoia; it’s

seriousness about safety basicsand respect for survivors who live with the consequences.

Conclusion: The Point Isn’t BundyIt’s Kathy

If you take only one thing from Kathy Kleiner Rubin’s story, let it be this: survival is not the end of the narrative.

It’s the start of a long negotiation with memory, fear, healing, and identity.

The night of January 15, 1978, is part of her history. It is not her entire name. And every time she tells her story on her own terms,

she does something Bundy never intended to allow: she reclaims the spotlight, the meaning, and the future.

Extra: 10 Survivor-Style “Life After” Experiences (500+ Words of Real-World Takeaways)

When people say, “I can’t imagine,” survivors often think, “Good. I hope you never have to.” But if you want to understand Kathy Kleiner Rubin’s

experienceand what it represents for survivors more broadlyfocus less on the sensational details and more on the lived realities that follow.

Here are ten “life after” experiences that regularly show up in survivor accounts, and that Kathy’s public reflections illustrate in a very

grounded way.

1) Your brain may protect you with weird rewrites

Shock can make reality feel unreal: sounds distort, time stretches, memories skip. Kathy describing emergency lights as a “carnival” is a classic

example of the mind grabbing a familiar label to survive an unfamiliar horror. That’s not weakness. That’s biology doing triage.

2) Healing is mostly inconvenient

People picture “recovery” as inspirational. Survivors know it’s also logistical: appointments, surgeries, paperwork, pain management, sleep that

never quite behaves, and the irritating fact that your body heals on its own schedule. When your jaw is wired or repaired, even eating becomes a

project. The world keeps moving while you learn how to swallow again.

3) Anger is a normal stage, not a personality flaw

Survivors often feel angry at the attacker, the situation, the system, and the randomness of it all. Kathy has spoken about anger and sadness

not as a dramatic confession, but as an honest inventory. Anger can be a sign that your sense of justice still works.

4) “Safety rituals” aren’t sillythey’re coping

Lock-checking, scanning rooms, sitting with your back to a wallthese habits can be your nervous system trying to regain control. Kathy has described

wanting to keep Bundy from inserting himself into daily life, which often means creating boundaries and routines that make you feel grounded. The goal

isn’t to eliminate every ritual; it’s to keep them from taking over.

5) Triggers can be random and rude

Survivors don’t get to pick what becomes a trigger. It can be the look of a log, the sound of a door, a news segment, or even an ordinary lock.

The solution isn’t to “toughen up.” It’s to learn what your body is signaling and build strategiestherapy, breathing tools, support systems,

and sometimes simply leaving the room without apologizing.

6) People will say the wrong thingoften trying to be nice

Survivors hear: “At least you’re alive,” “Everything happens for a reason,” or “You’re so strong!” (Sometimes “strong” just means you had no choice.)

Kathy’s story highlights a better approach: listen, believe, don’t romanticize, and don’t make survivors manage your feelings about their pain.

7) Your identity can feel “split” for a while

There’s the you-before and the you-after. Survivors often feel pressure to “go back to normal,” but normal may not exist in the same shape.

Kathy’s life illustrates a healthier target: build a new normal that includes joy, work, love, and meaningwithout letting the attacker become the

central character.

8) Telling your story can be healingor exhaustingor both

Kathy has said that talking about it can help her heal. Many survivors feel similarly, but only under the right conditions: when they control the

setting, the details, and the purpose. Sharing should be a choice, not a public duty. You don’t owe the world your trauma for “awareness.”

9) True crime can be validating, but it can also re-open wounds

Survivors may appreciate accurate storytelling that honors victims. They may also feel retraumatized by glamorization, jokes, or endless reboots that

treat their lives like a franchise. A good rule: if a piece of content makes the killer seem fascinating and the victims feel forgettable, it’s not

survivor-friendly media.

10) Recovery is not a straight lineand that’s still success

Survivors can be fine for years, then get knocked sideways by an anniversary date, a documentary trailer, or a life stressor. That doesn’t mean

they “failed to heal.” It means the body remembers. Kathy’s long-term perspective models something powerful: you can carry the memory without

letting it carry you.

If you’re reading this because you’ve been through something similar, the most important takeaway is practical, not poetic: you deserve support, you

deserve safety, and you deserve a life that’s bigger than what happened to you. Kathy Kleiner Rubin’s story resonates because it refuses the easiest

narrative (“monster vs. victim”) and insists on the harder truth: a survivor can build a full lifeand still speak honestly about the scars.