Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Two Crises, Two Very Different Backdrops

- Speed and Shape: How the Two Recessions Unfolded

- Policy: New Deal vs. Pandemic Playbook

- Markets, Psychology, and the “Wealth of Common Sense” Angle

- What We Learned from the Corona Crisis vs. the Great Depression

- of Real-World Experience and Common-Sense Takeaways

- Conclusion: Not the Same Crash, but the Same Call for Calm

If you’ve ever tried to make sense of the COVID-19 economic roller coaster by

comparing it with the Great Depression, you’re not alone. Investors, historians,

and armchair economists have all looked backward to the 1930s to ask the same

question: Was the corona crisis anything like the Great Depression?

Short answer: yes… and very much no. The two episodes share some big-picture

similarities sudden shocks, terrifying headlines, and massive government

interventions but they unfolded in wildly different ways. Understanding those

differences isn’t just trivia; it’s a powerful way to build the kind of

common sense that helps you stay calm the next time markets look scary.

Two Crises, Two Very Different Backdrops

The Great Depression: When the Bottom Really Fell Out

The Great Depression began with the 1929 stock market crash and spiraled into

a decade-long economic catastrophe. Between 1929 and 1933, U.S. real GDP

plunged by roughly 29%, unemployment shot up to about 25%, and thousands of

banks collapsed. Prices didn’t just stop rising they fell sharply. Deflation

made debts harder to pay and pulled the economy into a deeper downward spiral.

There was no modern social safety net. No federal deposit insurance, no broad

unemployment insurance as we know it, no central bank with a playbook for

crisis management. Policy mistakes like tight monetary policy and protectionist

tariffs turned what might have been a painful recession into the worst

economic downturn in modern U.S. history.

The Corona Crisis: A Sudden Stop, Not a Total Collapse

Fast-forward to 2020. Instead of a financial bubble bursting, the world

deliberately slammed the brakes on economic activity to slow a pandemic.

Lockdowns, travel bans, and business closures produced what some economists

called a “sudden stop” recession. In the United States, real GDP contracted

by about 3.5% for the year the largest drop since World War II, but nowhere

near Depression-level numbers. Unemployment spiked to 14.7% in April 2020, a

truly brutal figure, yet it began improving within months as businesses

cautiously reopened and stimulus money flowed.

The corona crisis felt like the world’s fastest crash course in macroeconomics:

one month the unemployment rate was near a 50-year low, and the next, tens of

millions of people were filing for benefits. But behind the chaos was a key

difference from the 1930s policy leaders had both the tools and the will

to hit the gas pedal hard.

Speed and Shape: How the Two Recessions Unfolded

The Great Depression: Long, Grinding, and Relentless

The Great Depression wasn’t just about how far the economy fell; it was about

how long it stayed down. Bank failures wiped out savings. Businesses collapsed

and never reopened. Farm foreclosures were rampant. Even after the worst years,

the recovery was slow, uneven, and fragile. Many people who lived through the

1930s carried those scars and that hyper-cautious attitude toward money

for the rest of their lives.

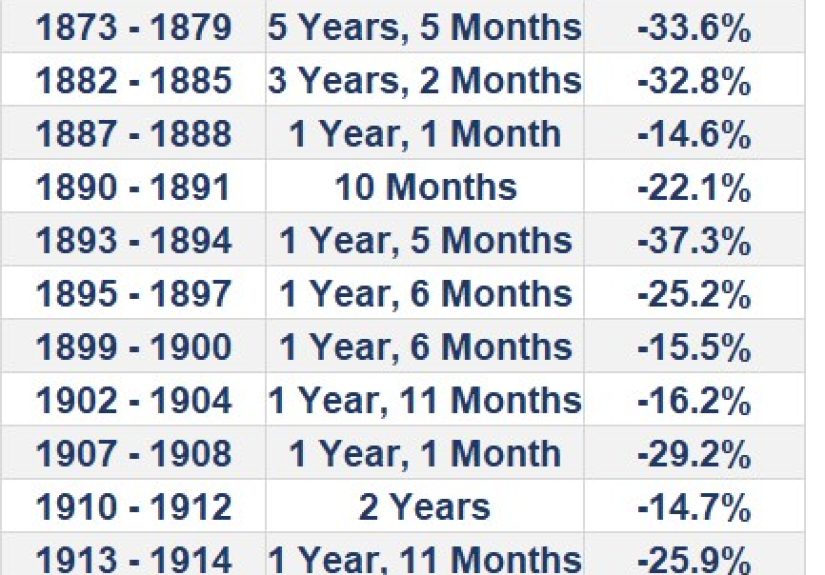

The stock market told the same grim story. After the 1929 crash, U.S. stocks

didn’t just bounce around for a few months and then recover. They continued

falling for years, ultimately losing around 80–90% of their value at the low

point in the early 1930s. If you were an investor back then, it didn’t just

feel like the bottom dropped out it felt like the floor disappeared and

someone turned off the lights.

The Corona Crisis: Violent Drop, Surprisingly Fast Rebound

The COVID market crash of early 2020 was incredibly fast. U.S. stocks went

from record highs in February to a bear market in a matter of weeks. Volatility

spiked to levels comparable to the worst days of the Great Depression. For a

moment, it felt like we were reliving the 1930s in fast-forward.

But then something very un-Depression-like happened: the rebound came almost

as quickly as the crash. Within months, stocks began recovering, boosted by

unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus. While certain industries, such as

travel and hospitality, remained deeply hurt, the overall economy shifted from

free-fall to partial recovery surprisingly fast. Instead of a decade-long

slump, the COVID recession officially lasted just a couple of months by some

measures, even though the human and social fallout lingered far longer.

Policy: New Deal vs. Pandemic Playbook

New Deal: Building the Safety Net While Falling

During the Great Depression, policymakers were essentially building the airplane

after it had already crashed. The New Deal created or expanded programs we now

take for granted: Social Security, federal jobs programs, banking reforms, and

infrastructure spending. It also reshaped the relationship between citizens and

the federal government, setting a precedent for Washington to step in more

aggressively during downturns.

Even so, the New Deal didn’t magically restore full employment overnight.

Unemployment remained painfully high through much of the 1930s, and some of the

recovery came only with the massive mobilization for World War II. The safety

net was stronger at the end of the decade than at the beginning, but people

lived through years of hardship before those protections were fully in place.

The COVID Response: Stimulus First, Questions Later

In 2020, leaders didn’t have to invent the concept of stimulus from scratch.

They simply super-sized it. Trillions of dollars in relief packages,

including direct checks to households, expanded unemployment benefits, loans

and grants to businesses, and aid to state and local governments, arrived

within weeks of the shutdowns. Central banks slashed interest rates to near

zero, launched massive bond-buying programs, and opened emergency lending

facilities.

The result? The immediate collapse was softened. Incomes for many lower- and

middle-income households actually held up or even increased temporarily due

to relief payments, even as job losses piled up. That doesn’t mean everyone

was fine far from it but the policy response prevented the sort of

cascading bank failures and long-term mass unemployment that defined the Great

Depression. The bill showed up later in the form of higher public debt and a

burst of inflation, but the short-term free-fall was stopped.

Markets, Psychology, and the “Wealth of Common Sense” Angle

Why Comparing Crises Can Be Dangerous (and Useful)

When the COVID crash hit, many people instinctively reached for the worst

historical analogy they could think of: “Is this the next Great Depression?”

That’s a natural emotional response our brains love dramatic stories but

it can be terrible for financial decision-making. Selling long-term investments

at the bottom because you’re sure this time is “just like the 1930s” is a

fast way to lock in losses and miss the eventual recovery.

A more useful form of comparison draws out how today’s conditions differ from

the past. In 2020, governments and central banks had decades of crisis

experience to draw on, from the Great Depression to the Great Recession.

Financial markets were deeper and more globally connected. Technology made it

possible for millions of people to work from home something unimaginable in

the 1930s. Those differences don’t make modern crises harmless, but they do

change the range of likely outcomes.

Behavior Matters More Than Forecasts

One of the core ideas behind a “wealth of common sense” approach is that

your behavior during a crisis matters more than your ability to

predict it. Few investors correctly forecast the pandemic, the lockdowns, or

the exact timing of the market crash. But anyone could choose how to react:

stick to a diversified, long-term plan, or panic and turn temporary volatility

into permanent loss.

During the Great Depression, many people didn’t have the luxury of long-term

investing. They were focused on survival. In the COVID era, more households

had retirement accounts, diversified mutual funds, and access to information

in real time. The challenge wasn’t just economic; it was psychological. Could

you ignore the flashing red headlines long enough to stay invested and let the

recovery do its work?

What We Learned from the Corona Crisis vs. the Great Depression

Lesson 1: Economic Data Can Look Terrible Without Signaling Another Depression

Double-digit unemployment and historic GDP declines sound like automatic

Depression territory, but context matters. The 2020 unemployment spike was

sharp and brutal, yet it was also partly the result of deliberate shutdowns

and came with a clearer path to reopening. The 1930s featured a slower-moving

and deeper collapse, with no clear endgame in sight, and far fewer policy tools

ready to go.

Lesson 2: Policy Choices Are Powerful

If the Great Depression taught policymakers one thing, it’s that doing too

little for too long can be catastrophic. The COVID response flipped that

script: do a lot, very quickly, and worry about the side effects later. The

trade-off showed up in higher public debt and post-pandemic inflation, but it

likely prevented the kind of decade-long slump that haunted the 1930s.

Lesson 3: For Investors, Resilience Beats Perfection

Both episodes reinforce a simple truth: you don’t need perfect foresight to

succeed as an investor. You need resilience. That means holding diversified

assets, keeping enough cash or safe investments to ride out downturns, and

resisting the urge to make all-or-nothing bets based on scary headlines. Crises

are inevitable; total wipeouts are usually optional.

of Real-World Experience and Common-Sense Takeaways

It’s one thing to read about these crises in history books; it’s another to

live through them. Fortunately, very few people alive today experienced both

the Great Depression and the COVID crisis as adults. But we can still draw

powerful insights from the stories we’ve inherited from the 1930s and the

experiences we just lived through in 2020 and beyond.

Ask anyone who grew up with grandparents from the Depression era and you’ll

notice a pattern: they saved everything. Coffee cans of spare change. Reused

foil. A freezer full of “just in case.” That extreme frugality wasn’t

irrational it was a survival strategy that had been burned into them by

years of scarcity and uncertainty. On the positive side, it meant they rarely

overextended themselves financially. On the downside, many of them avoided

investing in stocks for life, even when the long-term odds were firmly in

their favor.

Now look at the corona crisis generation. The shock was different, but the

emotional imprint is real. Many younger workers watched their jobs vanish

almost overnight, then reappear months later in hybrid or remote form. Some

discovered just how fragile their income was if it depended on tips, gigs, or

hourly work. Others, especially white-collar workers who could work from home,

saw their bank accounts swell because travel, dining out, and commuting costs

all dropped at once while stimulus checks arrived in the mail.

For investors, COVID was a stress test of every risk tolerance questionnaire

ever filled out in a calm market. It’s easy to click “aggressive” when stocks

are up and volatility is low. It’s harder when your portfolio is down 30% in a

month and the news is talking about refrigerated trucks outside hospitals.

Many people panicked and sold at or near the bottom. Others gritted their

teeth, stayed invested, or even rebalanced into stocks at lower prices. A few

lucky (or fearless) investors started buying when things looked bleakest and

were rewarded as markets recovered faster than almost anyone expected.

The common-sense lesson from both the Depression stories and the COVID

experience isn’t that you should be permanently scared or permanently

fearless. It’s that your financial life is more resilient when you plan for

both good times and bad. Having an emergency fund, manageable debt, and a

realistic understanding of your own risk tolerance makes it much easier to

ride out the next crisis without making panicked decisions you’ll regret.

Finally, both episodes remind us that economies recover, but people remember.

The Great Depression reshaped attitudes toward saving, government, and banks

for generations. The corona crisis will almost certainly leave its own

fingerprints: a greater comfort with remote work, more attention to

supply-chain risks, and perhaps a new appreciation for how quickly both

markets and daily life can change. If we’re smart, we’ll translate those

memories into practical steps diversified portfolios, thoughtful spending,

and policies that protect the vulnerable instead of either ignoring the

past or living in constant fear of it.

That is where a true “wealth of common sense” shows up: not in predicting the

next big crisis, but in building habits and systems that hold up no matter

what kind of headlines we’re reading.

Conclusion: Not the Same Crash, but the Same Call for Calm

The corona crisis was not a replay of the Great Depression, but it was a

powerful reminder that economies can seize up with shocking speed and that

policy choices matter enormously. The 1930s taught us what happens when

governments and central banks move too slowly and do too little. The COVID

era showed what happens when they move fast and do a lot including the

upside of a quicker recovery and the downside of higher debt and inflation.

For individuals and investors, the most useful takeaway isn’t a dramatic

headline comparison, but a calmer one: history doesn’t repeat exactly, but it

rhymes just enough to teach us better habits. If you use those lessons to

build a solid financial foundation, stay diversified, and keep your emotions

in check, you don’t have to fear every new crisis as “the next Great

Depression.” You just have to be ready for volatility and confident that,

over time, resilience tends to win.