Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Your Phone Has Gold (and Why It’s Not Just for Flexing)

- From Mountain to Motherboard: The Real Cost of “New” Gold

- Urban Mining: The Case for Getting Gold from Old Phones

- What Actually Happens When You Recycle a Phone

- How the Gold in Your Phone Helps the Planet (In Real Terms)

- What You Can Do (Without Becoming a Full-Time Recycling Influencer)

- Zooming Out: Why This Matters More Than One Device

- Conclusion: Your Old Phone Isn’t TrashIt’s a Tiny Mine

- Real-World Experiences That Make This Topic Feel Very Real (and Very Doable)

Your smartphone is basically a tiny, pocket-sized miracle: it takes photos, runs your life, and somehow knows you’re out of oat milk before you do.

But here’s the plot twistyour phone is also carrying a little stash of gold. Not “retire-to-a-private-island” gold, more like “buy-a-fancy-coffee” gold.

Still, when you multiply that tiny amount by the billions of phones in circulation, it turns into a serious environmental opportunity.

The idea is simple: instead of digging more gold out of the Earth (and paying the environmental price), we can recover gold and other valuable metals from old devices.

This is often called urban mining, and it’s one of the most practical climate wins hiding in plain sightprobably in the same drawer as your tangled chargers and mystery keys.

Why Your Phone Has Gold (and Why It’s Not Just for Flexing)

Gold shows up in smartphones because it’s excellent at conducting electricity and resisting corrosion. Translation: it helps your device stay reliable

even when it’s exposed to heat, humidity, and the emotional trauma of being dropped face-first onto a parking lot.

Where the gold lives inside a phone

Most of a phone’s gold is found in tiny componentsespecially on the printed circuit board (the “brain” area)including connectors, contacts, and some

microelectronics. You won’t see chunky nuggets; you’ll see microscopic layers doing quiet, heroic work so your phone can charge without drama.

How much gold are we talking?

A typical smartphone contains only a small amount of gold (measured in milligrams). That sounds laughably tinyuntil you realize how many phones are produced,

upgraded, traded in, or forgotten every year. Tiny times massive equals meaningful.

From Mountain to Motherboard: The Real Cost of “New” Gold

Gold mining isn’t just a shovel-and-pickaxe situation. Modern gold production can involve large-scale land disturbance, heavy energy use, and chemical processing.

In some places, mining has been linked to serious water pollution risks (including chemicals used to separate gold from ore), habitat destruction, and huge piles of

waste rock and tailings.

And while mining practices vary widely depending on the country, company, and scale, there’s a recurring theme: pulling brand-new gold out of the ground is

resource-intensive. Even when it’s done legally and with modern safeguards, it still tends to come with a hefty environmental footprint compared to recovering gold

from materials we’ve already extracted and refined once before.

Carbon and energy: gold is expensive in more ways than one

Producing gold can be energy-hungry, and energy often means emissions. Some life-cycle analyses estimate that the carbon footprint of producing gold can be

substantial per kilogramespecially when ore grades are low and more rock must be processed for the same amount of metal.

Mercury and the human side of gold

Another uncomfortable truth: in many regions, artisanal and small-scale gold mining has relied on mercury to bind gold during processing, creating serious health

risks for workers and surrounding communities. Even if your phone’s supply chain isn’t directly tied to those operations, global gold markets are interconnected,

and demand pressures don’t exist in a vacuum.

None of this means “all gold is evil.” It means gold is a high-impact materialso using the gold we’ve already mined (again and again) is one of the smartest

ways to reduce harm over time.

Urban Mining: The Case for Getting Gold from Old Phones

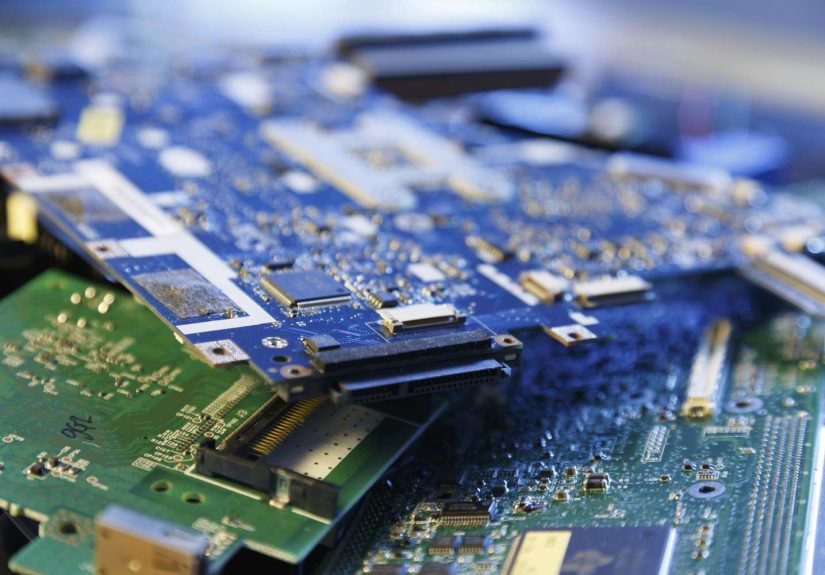

Urban mining is the recovery of valuable metals from discarded electronicsphones, laptops, tablets, circuit boards, and other e-waste. It’s a fancy name for a

very sensible idea: if we already dug it up once, let’s not waste it.

E-waste can be richer than ore

Here’s the mind-bender: certain electronics (especially circuit boards) can contain a much higher concentration of precious metals than many natural ores.

That’s because electronics are engineered from refined materialswe already did the hard part of concentrating and purifying those metals.

Some research-backed estimates suggest that, by weight, printed circuit boards and phone-related components can contain dramatically higher gold concentrations

than typical gold ore. This is why recyclers sometimes call e-waste an “above-ground mine.”

“But does recycling phones actually matter?”

Yesand not just in a symbolic, feel-good way. When phones are collected and processed responsibly, the recovered metals (including gold) can displace demand for

some portion of newly mined metals. The more efficient and widespread the collection systems become, the bigger the impact.

In the U.S., government and recycling organizations have long pointed out that large quantities of valuable metals can be recovered from bulk phone recycling.

In other words: one old phone doesn’t change the world; a million old phones absolutely can.

What Actually Happens When You Recycle a Phone

If you’re imagining someone panning for gold in a river of melted iPhones, please know that the real process is both less cinematic and more useful.

Responsible electronics recycling is typically a multi-step system designed to protect people, data, and the environment while recovering materials.

Step 1: Collection (a.k.a. getting phones out of the drawer)

Phones enter the recycling stream through retailer take-back programs, manufacturer trade-ins, donation organizations, municipal collection events, and dedicated

drop-off programs for devices and batteries. Convenience matters: the easier it is to drop off a device safely, the more devices get recovered.

Step 2: Data security and triage

Good recyclers treat your data like it’s radioactive (in a good way). Devices may be tested for reuse or refurbishment firstbecause extending a phone’s life is

often the highest-impact move. If a device can’t be reused, it moves to material recovery. Many responsible processors follow standards focused on safe handling

and data destruction practices.

Step 3: Dismantling and separation

Devices are dismantled or mechanically processed. Batteries are handled carefully (because punctured lithium batteries can cause firesnobody wants “surprise

pyrotechnics” at a recycling facility). Plastics, glass, aluminum, steel, and circuit boards are separated into streams.

Step 4: Precious metals recovery

Circuit boards and certain components go to specialized refiners. Recovery can involve shredding and advanced separation, followed by metallurgical processes

(often using heat and/or chemical methods) to isolate copper, gold, silver, palladium, and other metals. The goal is to recover high-purity metals that can be

used again in manufacturing.

When done responsibly, this is less “junkyard chaos” and more “industrial-grade unmixing of a very complicated layer cake.”

How the Gold in Your Phone Helps the Planet (In Real Terms)

1) Less mining pressure

Every gram of recovered gold can reduce the need to mine some amount of new gold. Since mining is often land- and energy-intensive, recovery can reduce

ecosystem disruption and emissionsespecially as recycling systems become more efficient.

2) Less toxic pollution risk

Reducing reliance on high-risk extractionespecially in regions where oversight is weakcan lower the chance of harmful pollutants entering waterways and

communities. Recycling isn’t automatically “clean,” but regulated, audited processing can be far safer than informal dumping or backyard burning.

3) A stronger circular economy

Recycling phones is one part of a bigger shift: designing products so materials circulate rather than getting trashed. Gold, copper, and aluminum are especially

valuable in a circular system because they can be recycled repeatedly without losing their core properties.

4) A financial incentive that actually works

Gold is valuable enough to help “pay for” recycling infrastructure. That matters because recycling systems need funding, logistics, labor, and safe processing.

Precious metals recovery can make the economics pencil outturning e-waste from a cost center into a resource stream.

What You Can Do (Without Becoming a Full-Time Recycling Influencer)

You don’t need to build a smelter in your garage. (Please don’t.) Here are realistic, high-impact actions that fit into normal human life.

Keep your phone longer if you can

The greenest phone is usually the one you don’t replace yet. A sturdy case, a screen protector, and a battery replacement can stretch a device’s life and reduce

demand for new materials.

Repair and refurbish when it makes sense

If your phone is slow, a storage clean-up or battery swap might bring it back. If the screen is cracked, repair can be cheaper than a new deviceespecially if

you’re not chasing the latest camera upgrade like it’s Olympic gold.

Trade in, donate, or recycle responsibly

If a phone still works, trade-in and donation programs can extend its life. If it’s dead, recycle through reputable collection channels. Look for programs that

emphasize responsible processing and strong data security practices.

Don’t toss phones in the trash

Aside from wasting valuable metals, improper disposal increases the risk that batteries and hazardous components end up in landfills or get handled unsafely.

Batteries especially deserve careful drop-off handling.

Zooming Out: Why This Matters More Than One Device

Global e-waste is growing fast, and documented recycling rates have struggled to keep up. That gap is where the opportunity lives. Phones are small, but they

represent a high-density package of valuable materials. The more we recover, the more we can reduce the environmental cost of our tech habits without giving up

the tech itself.

Also, electronics recycling isn’t just about materialsit’s about trust. People hesitate to recycle phones because they fear data leaks, don’t know where to go,

or assume recycling is pointless. Better standards, clearer programs, and easier drop-off options can change that.

Conclusion: Your Old Phone Isn’t TrashIt’s a Tiny Mine

The gold in your phone won’t buy you a yacht. But it can help build a future where we mine less, waste less, and reuse more. That’s the real flex:

turning yesterday’s gadgets into tomorrow’s resources.

So, if you have an old phone hiding in a drawer, congratulationsyou’re sitting on a mini urban mine. The planet would like you to stop hoarding it like a

squirrel with premium electronics and send it back into circulation.

Real-World Experiences That Make This Topic Feel Very Real (and Very Doable)

If you’ve ever tried to clean out a “tech drawer,” you already know the emotional arc: optimism (“I’ll organize everything!”), confusion (“Why do I have three

cables that don’t fit anything?”), and mild guilt (“Okay, I’ve been keeping this phone since… wow, since that haircut era.”).

That drawer is where the gold-to-planet connection stops being an abstract idea and starts being a practical choice.

One of the biggest experiences people report when recycling phones is data anxiety. It’s not irrationalour phones hold photos, bank apps,

private messages, and enough personal info to make your future self say, “Why did I screenshot that?” The moment you decide to recycle, the first hurdle is

feeling confident that your data will be gone for real. What helps is treating your phone like you’re moving out of an apartment: back up what you need, sign out

of accounts, disable find-my-device features, perform a factory reset, and remove SIM/SD cards if your model has them.

Another common experience: the “where do I even take this?” problem. People often mean well but get stuck because recycling isn’t as simple as

tossing a bottle in a blue bin. Phones combine glass, metals, andmost importantlybatteries. Many folks discover, usually after a quick search or a conversation

with a store employee, that certain retailers and community drop-off programs accept phones, and some battery-focused programs accept battery-embedded devices too.

Once you know a location exists, it feels less like an environmental lecture and more like an errand you can knock out between coffee and groceries.

There’s also the surprising experience of realizing how much value is trapped in something that feels worthless. A broken phone looks like a

lost cause, but recyclers see a collection of refined materials: aluminum frames, copper wiring, and precious metals on circuit boards. Many people feel a weird

satisfaction handing over a “dead” device and thinking, “Okay, you’re not going to rot in a landfillparts of you might come back as something useful.”

It’s the closest most of us will get to real-life alchemy.

Some experiences are less heartwarming and more practical: learning that batteries can be a fire risk if mishandled. People hear about

lithium-ion battery fires in waste streams and suddenly understand why careful drop-off matters. That tiny spicy pillow of energy inside your phone deserves a

respectful send-off. This isn’t about fearit’s about good process. Safe collection protects workers, facilities, and neighborhoods.

Finally, there’s the experience of talking about it with friends or family and realizing how common “drawer mining” is. Nearly everyone has an old phone, and

plenty of people have multiple. When one person shares a simple tiplike using a manufacturer trade-in, a local collection event, or a reputable drop-off

locatorothers often follow. That’s how small actions scale: not through perfect behavior, but through normal people making one better choice and making it easy

for someone else to copy it.

The biggest takeaway from these real-world moments is that phone recycling works best when it’s treated like a routine system, not a heroic mission. The goal

isn’t to be “the recycling person.” The goal is to turn old phones into recovered resourcesso the gold already in circulation keeps doing its job, without the

planet paying the price twice.