Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The song we think we know (and the verses we don’t)

- How the experts rank “This Land Is Your Land”

- Patriotic anthem or protest song? The great interpretive split

- Context is everything: how moments change the rankings

- How everyday listeners rank it

- So where should “This Land Is Your Land” really rank?

- What this song tells us about America

- Experiences and personal reflections on “This Land Is Your Land”

Try ranking American “patriotic” songs at a party and watch the room turn into a

very polite musical cage match. Someone will ride hard for “The Star-Spangled

Banner,” another will swear “America the Beautiful” is clearly superior, and

then a quiet voice in the corner says, “Actually… This Land Is Your Land

should be number one.” Suddenly, we’re not just talking about melodies anymore.

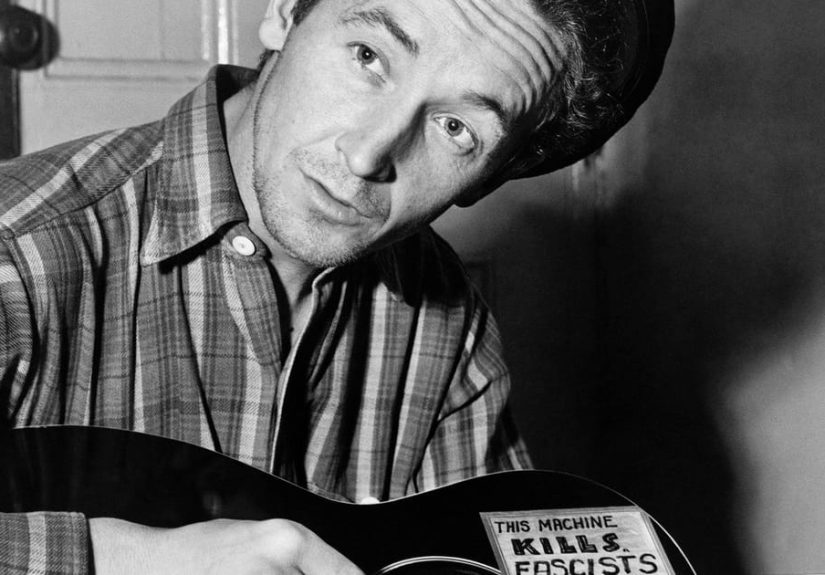

Woody Guthrie’s 1940 folk anthem lives in a weird, fascinating space. It’s sung by

kindergarteners, headlined by pop stars at the Super Bowl, quoted by protesters

in the streets, and listed by critics as one of the greatest songs ever written.

It’s both a campfire sing-along and a side-eye at economic injustice. No wonder

every attempt to rank it comes with a side order of debate.

In this deep dive, we’ll look at how major institutions, critics, and everyday

listeners rank “This Land Is Your Land,” why opinions about it are so divided,

and what the song’s shifting reputation says about America itself.

The song we think we know (and the verses we don’t)

On the surface, “This Land Is Your Land” seems simple enough. Guthrie wrote it

in 1940, partly as a response to hearing “God Bless America” over and over on

the radio. Where Irving Berlin’s hit sounded prayerful and triumphant, Guthrie

wanted something more grounded and skeptical – a song that loved the country

while still noticing who was being left out of the blessing.

The verses everyone knows paint a sweeping postcard of America: redwood forests,

Gulf Stream waters, diamond deserts. It sounds like a travel ad with a guitar.

But Guthrie also wrote additional verses about seeing hungry people at the

“relief office” and confronting a “No Trespassing” sign on a high wall – only

to discover that “on the backside it didn’t say nothin’.” Those tougher verses,

often omitted from school songbooks and official events, highlight inequality,

poverty, and private property blocking common people from the land around them.

That tension – between the pretty postcard and the pointed critique – is the

secret engine behind every ranking and opinion about this song. Are we judging

the softened, kid-friendly version, or the full, sharp-edged original?

How the experts rank “This Land Is Your Land”

Canon status: near the top of the American songbook

Before we hear from the internet, let’s look at the “official” tastemakers.

When the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and the National

Endowment for the Arts created their “Songs of the Century” list, Guthrie’s

tune landed near the very top, right alongside “Over the Rainbow” and

“White Christmas.” That’s a strong signal that cultural institutions see it

as one of the defining tracks of American life and history.

Rolling Stone has frequently included “This Land Is Your Land” in its rankings

of the greatest songs of all time, emphasizing how it became a “populist

national anthem” sung by everyone from folk revivalists in the 1960s to

Jennifer Lopez at a presidential inauguration. The takeaway: whether you view

it as protest or praise, the song sits firmly in the top tier of American music

history.

Patriotic playlists still love it

Modern patriotic playlists – especially those built around the Fourth of July –

continue to rank “This Land Is Your Land” near the top. Media outlets and

veterans’ groups that curate “best songs about America” almost always slot it

alongside “God Bless the USA,” “America the Beautiful,” and “The Star-Spangled

Banner.” They usually point out two big reasons:

-

It’s incredibly singable – simple melody, easy chorus, no nightmare high

note at the end. -

It feels inclusive – the repeated line “this land was made for you and me”

resonates in a way that sounds welcoming, not exclusive.

In other words, if you’re ranking songs by how easily a crowd can belt them

out around a barbecue without shattering glass, Guthrie’s tune scores very,

very high.

Patriotic anthem or protest song? The great interpretive split

Rankings get thorny once people bring the “lost” verses back into the picture.

Music historians and folk scholars often argue that the song is, at its core,

a protest anthem. Those extra verses about the relief office and private

property weren’t outtakes; they were the point. Guthrie had lived through the

Great Depression, traveled across dust-blown landscapes, and watched poor and

working-class people struggle. For him, singing “this land was made for you

and me” was as much a challenge as a celebration.

Some activists and critics go further, arguing that the song should rank higher

than more overtly patriotic tunes precisely because it refuses to ignore

injustice. In their view, a “real” American anthem should admit that the

country has flaws – and invite people to fix them. For these listeners, the

original version of “This Land Is Your Land” might be the number-one American

song, with everything else playing catch-up.

On the other hand, some listeners feel uneasy ranking a song so highly once

they dig into those verses. They may prefer patriotic music that sticks to

gratitude and praise, not critique. For them, “This Land Is Your Land” slides

down a few spots in the rankings when compared with more traditionally

reverent songs.

Context is everything: how moments change the rankings

If you notice that opinions about the song swing wildly depending on the year,

you’re not imagining it. “This Land Is Your Land” keeps popping up at big,

emotionally charged events, and each moment nudges its reputation in a new

direction.

When pop stars perform it at major sporting events or inaugurations, the song

is framed as a unifying, feel-good anthem. Millions hear the chorus, very few

hear the verses about hunger or “No Trespassing” signs. In that context, it

ranks as a safe, familiar patriotic crowd-pleaser.

But when protesters sing the full version at rallies, marches, or immigration

demonstrations, a different ranking emerges. The song suddenly sits near the

top of the “American protest playlist” – shoulder to shoulder with “We Shall

Overcome” and “Which Side Are You On?” It becomes a soundtrack for people

arguing that the land isn’t actually working for “you and me” yet, but it

should.

Even advertising has gotten involved. A Jeep Super Bowl commercial used a

glossy, globalized rendition of the song to sell SUVs, drawing criticism from

people who felt that pairing Guthrie’s anti-elitist folk anthem with a car ad

was… let’s say “a bold interpretive choice.” When brands co-opt the song this

way, some fans temporarily knock it down their personal rankings, frustrated

that its radical roots keep getting watered down.

How everyday listeners rank it

Outside the world of critics and ad agencies, regular listeners have their own

lively opinions. In online discussions and forums, you’ll see a few recurring

themes:

-

Many people rank “This Land Is Your Land” above “God Bless America”

specifically because of Guthrie’s skepticism about blind patriotism. -

Fans with childhood memories of singing it in school often rank it highly

for emotional reasons, even if they never learned the “hard” verses. -

Others place it in the middle of their lists because it feels overplayed or

because simpler tunes like “America the Beautiful” hit them harder

emotionally.

In short, public opinion doesn’t line up in a neat consensus. Instead, you get

a bell curve of sentiment: a big cluster that views it warmly as a classic,

a passionate group that treats it as the ultimate American song, and

a smaller group that quietly shrugs and says, “It’s fine, but I’m skipping to

the next track.”

So where should “This Land Is Your Land” really rank?

There’s no single correct ranking – but we can sketch a thoughtful, modern

placement based on how the song actually functions in American life:

Among all American songs, period

Considering its historical importance, influence on later artists, and

continuing use in major public moments, it’s reasonable to place “This Land

Is Your Land” in the top 10–15 American songs of all time. It’s hard to name

another folk tune that has simultaneously shaped politics, education,

advertising, and protest culture this deeply.

Among patriotic songs specifically

If we zoom in and look only at patriotic or America-themed songs, it arguably

deserves a top-three placement:

-

“America the Beautiful” often wins on pure emotional and

musical beauty. -

“The Star-Spangled Banner” wins by default as the official

national anthem (even if it’s a nightmare to sing). -

“This Land Is Your Land” wins as the people’s anthem –

rooted in folk tradition, aware of inequality, yet still hopeful.

So if we’re forced to hand out medals, “This Land Is Your Land” comfortably

takes a spot on the podium – not because it ignores America’s problems, but

because it refuses to.

What this song tells us about America

In the end, rankings are just numbers wearing fancy clothes. What matters more

is what the song reveals: that a truly lasting patriotic piece has to carry

more than just flag-waving. It has to hold contradictions – beauty and pain,

love and criticism, pride and humility.

“This Land Is Your Land” does exactly that. It’s a love letter to the land

and a complaint form about the system. It says, “This belongs to all of us,”

while quietly asking, “So why doesn’t it feel that way yet?” That paradox is

why the song has endured, why it keeps showing up in new contexts, and why

everyone still has strong opinions about where it belongs on “best of”

lists.

Maybe the most honest ranking we can give it is this: it’s not just “top 10”

or “top 3.” It’s one of the few songs that actually changes how people think

about what a patriotic song should be.

Experiences and personal reflections on “This Land Is Your Land”

Rankings are one thing; experiences are another. If you ask people to share

their personal stories connected to “This Land Is Your Land,” the song jumps

off the page and turns into something much more human than a number on a list.

For many Americans, the first encounter with the song happens in elementary

school. You’re standing on risers in a gym that smells faintly of crayons and

floor polish, squinting into bright lights while your music teacher waves her

arms like a very determined bird. You don’t know anything about the Great

Depression, or lost verses, or Woody Guthrie’s politics. You just know that

the melody is easy, the words feel friendly, and everybody gets to sing the

“you and me” line together. In that moment, the song ranks as “best thing

ever” simply because it feels like belonging.

Fast-forward a decade or two. Maybe you hear the song again at a protest –

chanted, half-sung, over the noise of traffic and megaphones. This time

someone includes the verses about hunger and “No Trespassing” signs. The same

chorus you sang as a kid suddenly lands differently. You realize that the song

you filed away as “cute and patriotic” is actually wrestling with who gets

access to resources, who owns the land, and who is left standing in line

outside the relief office. Your internal ranking quietly updates: this isn’t

just a campfire classic; it’s a political statement with a deceptively simple

hook.

Then there are the big televised moments – Super Bowl halftime shows, national

memorials, presidential inaugurations. You’re on the couch, probably holding a

snack, and a famous singer steps up and launches into “This Land Is Your

Land.” The camera pans over fireworks, skylines, and waving flags. Most of the

time, you only hear the first few picturesque verses. It feels unifying,

sentimental, and safe. Even if you know the song’s tougher lines, it’s hard

not to be moved; there’s something powerful about millions of people sharing

the same melody at the same time. For a lot of viewers, those are the moments

that push the song back up their mental rankings: “Oh right, this really is

one of the big ones.”

Some experiences are quieter. Maybe you’ve sung it around a campfire in a

national park, or while driving across flat, endless highways with the radio

turned up just to keep you awake. In those settings, the lyrics about “the

ribbon of highway” and “the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts” feel less

like poetry and more like a travel diary. The song becomes a kind of

soundtrack for noticing the landscape: mountains, fields, small towns, and

the occasional questionable roadside attraction. It’s easy in those moments

to feel the generosity in Guthrie’s refrain – the sense that the land, at

least, really is for everyone to see and enjoy.

Other experiences are more conflicted. People who have struggled with

eviction, job loss, discrimination, or immigration status sometimes talk about

hearing “this land was made for you and me” and feeling, frankly, unconvinced.

For them, the song can land as both an aspiration and a challenge. It

highlights the gap between American ideals and daily reality. Instead of

pushing the song down their rankings, that tension often makes it feel more

honest. They may not sing it with uncomplicated pride, but they might sing it

with determination: a reminder that the promise is still unfulfilled, and

therefore still worth fighting for.

Put all these experiences together and you get a messy, beautiful picture.

“This Land Is Your Land” is a children’s song, a protest anthem, a stadium

sing-along, a road-trip soundtrack, and a memory trigger all at once. Your

personal ranking will probably change depending on which version of yourself

is listening: the kid on the risers, the adult in the crowd, the viewer on the

couch, or the traveler watching the country scroll past the windshield.

That might be the most compelling argument for placing it near the top of

any list: very few songs stay relevant as your life changes. This one does.

It grows with you, it argues with you, and it keeps asking the same haunting,

hopeful question: if this land was made for you and me, what are we going to

do to make that feel true?